Is the VAT increase regressive?

- Published

Some may rush to save money, while others may feel they can afford to avoid the crowds

Labour maintains that the VAT rise to 20% hits the poorest families hardest.

Yet the Chancellor, George Osborne, told the BBC on Tuesday that he thinks targeting VAT is more "progressive" than increasing income tax or National Insurance.

A progressive tax is one that places the biggest burden on those most able to pay. A regressive tax does the opposite.

So who is right?

Mixed messages

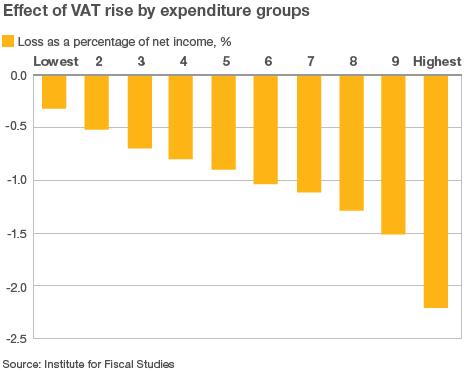

Treasury data shows that the UK households that spend the most also tend to have their incomes harder hit by the VAT rise than the lowest-spending households.

This would appear to support the Chancellor's claim.

However, when economists consider how "progressive" or "regressive" a tax is, they typically look at the distribution of the tax burden based on household income, not household spending.

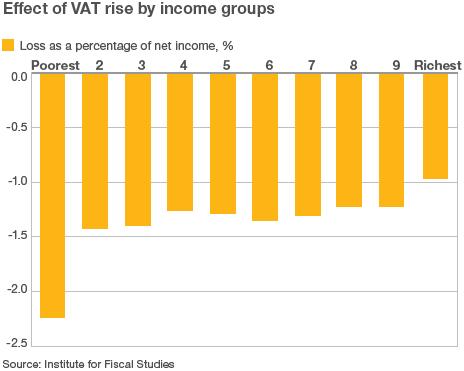

This is exactly what the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) did last year, external to coincide with Mr Osborne's emergency budget.

And the data here tells exactly the opposite story: those at the bottom of the income scale - particularly the bottom 10% - would be hurt much more by the VAT rise than those at the top.

How can this be?

Borrowing and saving

An important reason is that low earners have to spend a much bigger share of their income than high earners in order to meet their basic needs.

To put it another way, top earners typically have much more of their annual income left over after they have bought everything they need or want.

In contrast, many poorer families ran down their savings - or even borrowed money - in order to maintain their spending levels during the recession.

Indeed, in a recent survey of household finances, external, the Bank of England expressed concerns about the growing burden of unsecured debt for many households.

So presumably this means the tax is regressive - low earners spend more of their income and so end up paying disproportionately more VAT, right?

Defining the poor

Not necessarily.

The IFS questions whether this traditional incomes-based approach is accurate.

They point out that a lot of low income households do not meet most people's definition of "poor".

The bottom 10% of earners includes pensioners living off their savings, wealthy individuals without a job, or those with volatile incomes who had a fallow year.

For this reason, the Chancellor may be right that we should look at how much people spend - rather than what they earn - as a more accurate measure of their financial position.

So why do higher spenders pay proportionately more VAT?

Bare necessities

Partly it is to do with what they spend their money on.

Many basic items, such as food and children's clothing, are not subject to VAT, external, while household energy bills are taxed at a lower 5% rate - and that lower rate is not being raised.

Lower-spending - and lower-income - families are likely to spend a bigger share of their money on these basic items, so VAT tends to be a smaller percentage of their household bills.

Moreover, households facing tighter finances might be expected to spend less on high-VAT items such as a new car or new furniture, cushioning the blow.

Nonetheless, some items that households may deem essential are taxed at the standard rate, which has just risen - notably petrol, which was also hit by a New Year rise in fuel duty.

Hey big spender

All this sounds reasonably progressive.

But there could also be something else going on in the data, because a lot of spending can be quite lumpy.

A "big spender" in one year may be someone who has just moved into a new home and bought a lot of furniture and other big ticket items.

Or it could be someone who has just bought a new car on credit to last the next 10 years.

This person would show up towards the higher end of the spending scale, even though they may not earn much, and in other years they would not spend so much.

And all of those big one-off purchases would have been subject to VAT, meaning this person would be hard-hit by the VAT rise.

Alternatives

Some may say these arguments are a bit academic and ignore Mr Osborne's point that VAT is more progressive compared with other possible revenue-raising options.

Labour's claim of unfairness is questioned by Adrian Houstoun, from the chartered accountancy firm Kingston Smith.

"If we weren't to raise this amount of money from the VAT rise, it would have to be from something like National Insurance," he says.

He notes that - unlike with National Insurance, which is levied on people's incomes - households can reduce their VAT bill, because they have a small degree of flexibility over what they spend their money on.

Moreover, the way in which National Insurance is levied may be considered more regressive than VAT.

Employees' National Insurance Contributions drop from 11% of earnings to only 1% above a threshold of just under £44,000 - meaning top earners pay a lower all-in rate.

Contrast that with VAT, where everyone pays the same tax rate for the same items.

Yet the government already plans to increase National Insurance from this April, and is doing it in a way that makes it less regressive - by raising the rates to 12% and 2%.

Moreover, the government did have another more unambiguously progressive option, which was to raise more money through income tax.

Income tax bands and allowances are specifically designed to ensure the poorest pay least.

- Published4 January 2011

- Published4 January 2011

- Published30 December 2010