Can Europe benefit from shale gas?

- Published

Getting gas from rocks is relatively easy, though there are concerns about the cost and about the impact on the environment

In a field near Kirkham, between Preston and Blackpool, they are preparing to drill a well that many say could change our energy outlook.

Up until recently, most economists had forecast gas prices rising sharply as supplies become scarce. Production in the North Sea is already falling fast.

But the recession saw prices fall and now the process of getting gas out of rocks, shale gas as it's known, could bring huge new supplies.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that "unconventional" resources such as shale could double our gas supply worldwide.

Gas for 100 years

At the well in Lancashire, they are preparing to see if the right conditions exist in the UK to get gas from shale.

Even as they do so, environmentalists - backed by a new report - have called for the practice to be stopped. Some economists, meanwhile, have warned it may yet prove costly to do outside the US.

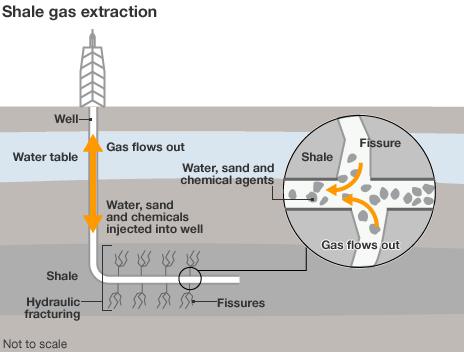

Shale gas is extracted using a process called fracking. It involves small explosions to fracture the rock, followed by a slurry of water, sand and chemicals to free the gas trapped inside.

IHS Cambridge Energy Research Associates estimate the amount of available gas in the US has doubled in recent years and the US Energy Information Administration's latest figures for 2008-09 showed an 11% increase in economically recoverable gas for that one year.

The new supply has driven down the price.

"The recession happened at the same time as all the shale production, demand wasn't there and supply was just coming out of our ears," says Mary Barcella from IHS Cambridge Energy Research Associates.

European boom?

It has also led to interest from the oil majors.

Shale gas finds have reduced US demand for liquidised natural gas shipped in in tankers

Shell recently invested more than £3bn to buy the shale assets of US producer East Resources. By 2012, the company expects half its production to come from gas of one form or another.

Plentiful cheap gas has opened up the prospect of US power companies switching from coal and therefore significantly reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

But the problem with gas is it that it is notoriously difficult to transport.

Following the US lead, shale is being explored in China, South America and Europe - the world's largest market for gas.

The IEA estimates that at current usage levels, there is enough conventional gas to last the world a limited 60 years - but if one factors in remaining recoverable reserves including shale, that number increases to 250 years.

It is a tempting prospect.

The main focus so far has been on Poland and Germany.

Though Shell, Exxon and ConocoPhillips are all reportedly involved in early trials on the continent, none of the major firms have yet outlined any plans for extraction.

In the UK, gas prices also fell after 2008, but have slowly risen again, leading energy companies to raise prices for consumers and prompting calls for shale reserves to be tapped.

Attention is focused on little-known Cuadrilla Resources and its well in Lancashire, where it plans a test drill soon.

"If we were successful and show reserves then there would be interest from bigger companies," says manager Mark Miller.

'Not under our backyard'

But Europe has little history of onshore drilling.

The first shale well was dug in 2008, and there is a public reluctance to engage in new underground projects.

Experiments in carbon capture and storage have run into trouble in the Netherlands and Germany because of widespread public opposition and the shale gas industry has already been criticised.

A new film, Gaslands, includes scenes of a man setting light to water from a tap because - he alleges - methane has seeped into the water supply due to fracking.

A report out this week by the UK's Tyndall Centre cited such worries to call for a moratorium on shale gas drilling in the country.

Economic problems

But the abundance of US shale has had a knock-on effect on the rest of the world.

Tankers of gas previously destined for US ports now need to find a new dock.

"There is an excess of gas supply at the moment," says Edmond George from the Economist Intelligence Unit.

"Companies are over-contracted and there are many LNG cargos which are not being sold."

Demand has picked up during the winter, but even so shale may not provide an affordable answer, at least in Europe.

A report by Florence Geny, for the Oxford Institute for Energy studies in the UK, suggested drilling costs would be two to three times higher than in the US, with water costs up to 10 times higher.

That is if you can find anywhere to put the wells.

"The number of wells required is very great," says Ms Geny.

"The way you can distribute the wells on the surface is very restricted, due to regulation and high levels of urbanisation."

Anne Sophie Corbeau from the IEA agrees with her assessment.

"It would take at least 10 years to have significant gas production, if any," she warns.

Chinese consumption?

There is also the question of what the gas would be used for.

The UK recently reformed its energy market to discourage short term investments in gas for electricity.

"For us, a big uncertainty is China," warns Ms Corbeau.

"In 2010, their demand is estimated to have increased by around 20%, putting them above any European country."

Higher demand would counter-act higher supply, pushing up the price.

It would also mean even shale reserves look far less generous - something the IEA is working on calculating.

Supply worries, and a stable high price could prompt European countries to accelerate shale gas development - or to turn away from gas as pricey and limited.

Even Cuadrilla's Mr Miller admits it will be "several years at least" until shale gas comes on-stream in the UK.

By then the situation my look very different.

- Published20 January 2011

- Published19 January 2011

- Published17 January 2011

- Published10 December 2010