Youth unemployment: A smouldering fuse?

- Published

There is a danger that youths without work or training will lose all connections with the job market

Abdul Tahir is in his final year at university and fully expects to get good results when he takes his exams in June.

His expectations are much lower for his future prospects, however.

Speaking at his campus in West London, he acknowledges that his chances of landing a job when he leaves university are very slim.

"There will be 200 of us leaving at the same time," he says, "and we will all be chasing after the few positions that might be available."

Looking for a job is a plight all too familiar to millions of young people around the world.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), youth unemployment has been rising dramatically and the trend is set to continue in 2011.

Experience required

The average level of youth unemployment among 15 to 24 year olds has traditionally been double that of over-25s.

It is a global phenomenon, with many countries experiencing youth unemployment figures in the region of 17-25%.

In countries such as Yemen it is even worse, with youth unemployment figures estimated to be closer to 40%.

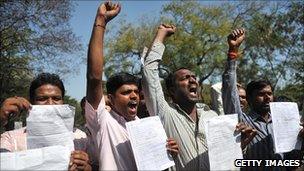

Youth unemployment has been one of the underlying causes behind the political upheaval across North Africa, which began in the middle of December.

"Youth unemployment is a serious problem which governments must urgently tackle," says Glenda Quintini, an economist with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

It is a problem the OECD has flagged up for several years, one it feels will remain for many more years, not least as it was exacerbated by the financial crisis.

As governments slash budgets in the aftermath of the financial crisis, about 25 million people across the European Union (EU) have been made jobless.

Global prospects for jobs are bleak in these difficult times, particularly for the next generation of workers - those who are leaving education now.

Jeff Jeorres, chief executive of the employment agency Manpower, says that during the economic downturn, companies have been looking for experience when they hire people.

"Companies are looking for someone to start and be very productive from the first minute on the job," he says.

"That is a disadvantage for a youth who maybe comes with a great degree and a willingness to work," he explains. "Companies can find that without having to go to the youth workforce."

One of the perennial problems is that companies cannot afford to hire and then train young people.

Many young people think their education was a waste of time if they cannot find work afterwards

This is especially difficult for manufacturers.

"While they would like to hire at that younger range, they are finding that they can get very productive experienced workers to plug the gaps a lot faster," Mr Jeorres points out.

He is fully aware that the problem is not going to be easy to solve.

"We know how many 13-year-olds are going to be working in five or six years from now and we know there is going to be a hole in the labour market," he says.

"That hole is going to be even more exaggerated because that part of the workforce is not going to have the experience required to take up the slack of retirees and the normal course of what is happening with an ageing workforce across the world."

He points to countries such as Japan, Italy and France, where there are some severe demographics where you have an ageing population and a birthrate that is not going to keep up.

More focus needed

There are forward-looking companies, in particular those that have the financial wherewithal to make sure their internship programmes and university recruitment programmes are intact and improving.

But the majority of companies are facing a challenge to offer similar schemes because of the affordability.

'A bachelor is not enough'

Studying subjects that have no direct application to commercial life, makes it more difficult for young people to find work or develop the right skills.

"We still talk to companies that say they would like the critical thinking and problem solving that comes with a noble arts degree," Manpower's Mr Jeorres says.

"At the same time, however, they are looking for more specifics."

Ms Quintini at the OECD maintains that young people should be more aware of the options open to them before continuing their academic pursuits.

"Teachers and job advisers should explain more thoroughly what is needed in the workforce," she says.

"Some young people might be better prepared if they chose a vocational course rather than a university degree," she says, "whilst others might benefit from studying a degree with a specific focus."

Her sentiments are echoed by Abdul Tahir, who will graduate with a bachelors degree in the summer.

"I know it is going to be difficult to find a job," he says, "So I will stay on at university and take a masters degree."

He intends to concentrate on one particular aspect of his chosen subject, a move he believes will give him an advantage over his peers when searching for a job.

There is the belief that a bachelor degree is not enough, that a masters degree is needed, then an internship to understand the company, and then there might be an offer of a job.

Whatever the situation, there are still more students globally than there are jobs.

Back to basics

Much of the sharpest pain is being felt in the developing economies.

In India, job creation dwindled during the financial crisis, but has since picked up after the government introduced measures to get the nation into work.

The economy is predicted to rise about 8% over the coming year, yet getting hired is not always straight forward.

Companies in India complain that students are not suitably qualified for the jobs on offer

India's growing population is expected to be the largest contributor to the global labour force in the fist part of this century. Some estimates show that the number of people able to work will grow by a third in the next 15 years.

The country will need those people to help fuel its growing economy, but although the supply seems secure, there are worrying areas of weakness.

Many employers complain they cannot find graduates with the right skills to fill vacancies.

"One of the problems of labour shortage in India has to do with the fact that a large part of the people in that age group are not really well trained," says Laveesh Bhandari from Indicus Analytics.

"Right now it is a three-to-five year problem in India," he says, "but we expect that to improve over the next decade as the education establishment gets its act together."

Unrealistic expectations

One important factor the country has experienced is that agriculture is no longer the defining sector in the Indian economy.

And as the service sector becomes more and more mature, the types of jobs on offer have changed.

One particular concern for Mr Bhandari is that poorly trained and educated people are graduating with degrees .

"First we have to start with the three Rs, which have not been the focus of the education system," he says

"The next critical problem has to do with the absence of vocational training, which is currently absent in the public sector-controlled universities and schools," he adds.

He also notes that young people do not have realistic expectations with regards to the workplace

"They think any degree will get them a white-collar job," he says.

Those people might be better advised to choose a vocational qualification, or to follow Abdul Tahir's example and become more focussed on one specific sector of their chosen career.

- Published19 January 2011