Oil price: Should we fear the latest rises?

- Published

Shades of the 1970s..?

The oil price has a nasty habit of predicting global recessions.

The 1973 Yom Kippur War and the 1979 Iranian revolution both led to jumps in the oil price that presaged economic downturns.

More recently, the recession of 2008-09 was preceded by a record run-up in the price of oil and other commodities.

With energy prices already well on the rise before the latest crisis hit the Middle East and North Africa, is the global economy headed for another tumble?

Trouble and bubble

First a little history.

Oil is an international commodity whose price is set by global supply and demand.

The oil price shocks of the 1970s were very much a supply-side story: crises in the Middle East disrupted oil exports, sending prices spiralling and helping to feed stagflation in the West.

Perhaps the most important outcome was that it strengthened the hand of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec), who were able to limit global supply and sustain a higher oil price long after the crises were over.

In contrast, the 2007-08 commodities bubble - in which crude oil played a leading role - was quite a different story.

...or the more recent commodity bubble?

Many have blamed that incident on financial speculators, but economist Paul Krugman argues that really the problem was global demand.

With populations and incomes steadily increasing in Asia, there seemed to be an inexorable rise in global energy demand.

And with a finite limit to the amount of hydrocarbons in the ground, "peak oil" - the point where global oil production reaches its highest practicable rate - became the buzzword.

Double whammy

So what do we face now? The 1970s or 2008?

Unfortunately the answer could be a combination of both.

Shortly before the latest turmoil in the Middle East began, Professor Krugman was already arguing, external that the strong global recovery - underway everywhere outside the forlorn West - was leading to exactly the same economic conditions that spawned the previous spike in commodity prices.

And the problem is not only manifesting itself in energy prices - food, metal and cotton prices are also well on the up again.

"What the commodity markets are telling us is that we're living in a finite world, in which the rapid growth of emerging economies is placing pressure on limited supplies of raw materials, pushing up their prices," he said.

Now, with Libya added into the mix, the price of Brent crude has more-than-tripled since hitting rock bottom in December 2008.

And it is only about 20% below the all-time high it set in July 2008, just before the global financial crisis.

Stretching and spreading

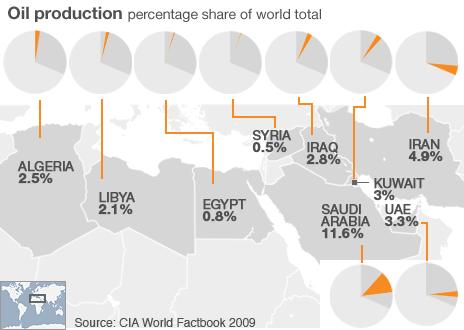

But how significant is Libya, you may ask.

After all, the country is responsible for only 2% of global oil production, although its share of the European market is estimated at about 10%.

So far it is estimated that between a third and a half of Libya's oil exports have been disrupted.

But even if all of its 1.6 million barrels of oil per day were shut down, Saudi Arabia - the world's biggest oil producer - has promised to step in with extra supply.

The Saudis - who dominate Opec - say they have an extra 4 million barrels in spare capacity, so what's the problem?

Declan Curry explains who gets the money you spend on petrol

First of all, thanks to resurgent global demand, spare capacity is already extremely stretched, and what the Saudis have to offer is pretty much it.

Secondly, markets are worried about trouble spreading well beyond just Libya.

Protests and a government crackdown have already been seen in Iran - a much bigger oil producer - as well as in Bahrain, gas-rich Algeria, and more recently in Oman.

Out of pocket

So does that mean we are headed for another recession if the oil price keeps climbing?

Well, not necessarily.

Economies have had four decades to get used to high and volatile energy prices, with the result that people - particularly Europeans - use energy much more efficiently these days.

Nonetheless, many economists say the 2007-08 commodities bubble did play a role in the subsequent financial crisis and recession in the West.

The argument goes that rising food and energy bills were what tipped already overstretched sub-prime borrowers into outright default on their mortgages, toppling the first in a series of financial dominoes.

However, now that the property bubbles in the US and Europe - though perhaps not in the UK - have been lanced, the same financial meltdown is hopefully less likely to be repeated.

Instead, what the higher oil price will probably mean this time round - but only if it remains elevated for several months, and starts being passed through to consumers - is a further squeeze on household budgets.

And this is likely to be particularly painful for low income households in the West, who spend the biggest proportion of their incomes on energy.

Price worth paying?

What is slightly more alarming is that the price rise comes at a time when central banks are under growing pressure to start raising interest rates again.

And this is particularly the case in the UK where inflation is currently running at twice the Bank of England's target.

Something else to worry about

If the oil price remained at $120 per barrel, it would cause a one-off increase in UK retail prices inflation of 0.48%, according to research by Andrew Clare of Fathom Financial Consulting, external.

In Europe and the energy-inefficient US, the impact on consumer prices would be 0.51% and 1.63% respectively.

If it rose to $150 - and stayed there - the impact would be doubled.

The dilemma for Western monetary policy is particularly unpleasant, because the only way for them to keep inflation down is by punishing households in their countries even more by increasing their borrowing costs.

All the same, it is too early to say whether the oil price will remain high for long enough for such doom and gloom to ensue.

And if it means the world gets a stable and democratic Middle East, then perhaps it is a price worth paying.

- Published24 February 2011

- Published22 February 2011

- Published21 February 2011