Graduates - the new measure of power

- Published

Watch: How Aalto University in Finland is teaching Chinese students in English

At the beginning of the last century, the power of nations might have been measured in battleships and coal.

In this century it's as likely to be graduates.

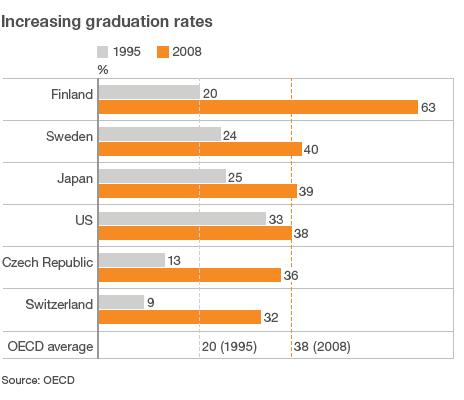

There has been an unprecedented global surge in the numbers of young people going to university.

Among the developed OECD countries, graduation rates have almost doubled since the mid-1990s.

China's plans are not so much an upward incline as a vertical take-off.

In 1998, there were only about a million students in China. Within a decade, it had become the biggest university system in the world.

Figures last month from China's education ministry reported more than 34 million graduates in the past four years. By 2020 there will be 35.5 million students enrolled.

The president of Yale described this as the fastest such expansion in human history.

Inextricably linked with this expansion has been another phenomenon - the globalisation of universities.

Global networks

There are more universities operating in other countries, recruiting students from overseas, setting up partnerships, providing online degrees and teaching in other languages than ever before.

Chinese students are taking degrees taught in English in Finnish universities; the Sorbonne is awarding French degrees in Abu Dhabi; US universities are opening in China and South Korean universities are switching teaching to English so they can compete with everyone else.

It's like one of those board games where all the players are trying to move on to everyone else's squares.

It's not simply a case of western universities looking for new markets. Many countries in the Middle East and Asia are deliberately seeking overseas universities, as a way of fast-forwarding a research base.

In Qatar, the purpose-built Education City now has branches of eight overseas universities, with more to follow. Shanghai is set to be another magnet for international campuses.

'Idea capitals'

This global network is the way of the future, says John Sexton, president of New York University.

"There's a world view that universities, and the most talented people in universities, will operate beyond sovereignty.

"Much like in the renaissance in Europe, when the talent class and the creative class travelled among the great idea capitals, so in the 21st century, the people who carry the ideas that will shape the future will travel among the capitals.

"But instead of old European names it will be names like Shanghai and Abu Dhabi and London and New York. Those universities will be populated by those high-talent people."

New York University, one of the biggest private universities in the US, has campuses in New York and Abu Dhabi, with plans for another in Shanghai. It also has a further 16 academic centres around the world.

Mr Sexton sets out a different kind of map of the world, in which universities, with bases in several cities, become the hubs for the economies of the future, "magnetising talent" and providing the ideas and energy to drive economic innovation.

Universities are also being used as flag carriers for national economic ambitions - driving forward modernisation plans.

For some it's been a spectacularly fast rise. According to the OECD, in the 1960s South Korea had a similar national wealth to Afghanistan. Now it tops international education league tables and has some of the highest-rated universities in the world.

The Pohang University of Science and Technology in South Korea was only founded in 1986 - and is now in the top 30 of the Times Higher's global league table, elbowing past many ancient and venerable institutions.

It also wants to compete on an international stage so the university has decided that all its graduate programmes should be taught in English rather than Korean.

Spending power

Philip Altbach, director of the Centre for International Higher Education, based in Boston College in the United States, says governments want to use universities to upgrade their workforce and develop hi-tech industries.

The first French-speaking university in the Gulf, a branch of the Sorbonne, was opened last month

"Universities are being seen as a key to the new economies, they're trying to grow the knowledge economy by building a base in universities," says Professor Altbach.

Families, from rural China to eastern Europe, are also seeing university as a way of helping their children to get higher-paid jobs. A growing middle-class in India is pushing an expansion in places.

Universities also stand to gain from recruiting overseas. "Universities in the rich countries are making big bucks," he says. This international trade is worth at least $50 billion a year, he estimates, the lion's share currently being claimed by the US.

If there are parallels with economic and political rivalries, the US remains the academic superpower, not least because of the raw wealth of its top universities.

Despite its investments taking a hammering from the financial crisis, Harvard sits on an endowment worth $27.4bn and spends more than $3.5bn a year.

It means that for every one dollar spent by a leading European university such as the London School Economics, Harvard can spend almost $10.

Even the poorest Ivy League university in the US will have an endowment bigger than the gross domestic product of many African countries.

Facebook generation

The success of the US system is not just about funding, says Professor Altbach. It's also because it's well run and research is effectively organised. "Of course there are lots of lousy institutions in the US, but overall the system works well."

The status of the US system has been bolstered by the link between its university research and developing hi-tech industries. Icons of the internet-age such Google and Facebook grew out of US campuses.

"Developed economies are already highly dependent on universities and if anything that reliance will increase," says the UK's universities minister, David Willetts.

And he says that globalisation in higher education is increasing in pace and "going to go a lot further".

"The rapid increase in international students, not just in the UK but in other countries with high quality universities, is a case in point.

"Universities are internationalised along other fronts too - for example, in the research that they do, which often has greater impact when conducted in collaboration with institutions in other countries."

University of laptop

Technology, much of it hatched on university campuses, is also changing higher education and blurring national boundaries.

Online services such as Apple's iTunes U gives public access to lectures from more than 800 universities and more than 300 million have been downloaded. And where else would a chemistry lecture get to be a chart topper?

New York University in Abu Dhabi: The university's president says this is the era of "global networks"

It raises many questions too. What are the expectations of this Facebook generation? They might have degrees and be able to see what is happening on the other side of the world, but will there be enough jobs to match their ambitions?

Who is going to pay for such an expanded university system? And what about those who will struggle to afford a place?

But Mr Willetts says that globalisation is having a "positive impact" for students, academics and employers.

And Professor Sexton remains optimistic that globalism will be about co-operation as much as competition and he summons up the forward-looking attitude of immigrants arriving in New York.

"The immigrant is always looking forwards to a better tomorrow, not looking back to a golden age."