Turning knowledge into the new oil

- Published

Katy Watson, from Middle East Business Report, on Qatar's drive to become a 'global knowledge hub'

It might seem like pouring water onto sand - almost literally - but the Gulf kingdom of Qatar is banking on a remarkable transformation in its fortunes.

The small but fabulously wealthy state is using its hydrocarbon earnings to try to convert itself into a global knowledge hub.

Billions of pounds are being pumped into a 2,500-acre complex for 80 educational, research, science and community development organisations, under the umbrella name of Education City.

The astonishing physical transformation of the desert is nothing compared with the long-term ambition to be a cradle of innovation, based in the Middle East but global in scope and impact.

The country knows that its hydrocarbon resources, which have given it the second highest per capita income in the world, will eventually run out.

"Future economic success will increasingly depend on the ability of the Qatari people to deal with a new international order that is knowledge-based and extremely competitive," says the country's proposals set out in its National Vision.

Qatar is a desert peninsula of only 4,500 square miles (11,655 sq km), with a native population of under a million - about as many as Norfolk in the UK.

Rising economies

It is up against some of the biggest emerging players in the world economy, notably China and soon India, with their vast physical and human resources and, increasingly, higher education campuses.

Texas A&M University in Qatar launched its first masters degree courses this year

The driving force is Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development.

So far it has attracted some notable US universities - Georgetown, Weill Cornell Medical College, Texas A&M, Virginia Commonwealth and Northwestern - as well as the French business school HEC Paris.

Education City's associate vice-president for higher education, Dr Ahmad Hasnah, says they have been strategically selected to span the broad spectrum of educational subjects in order to offer students a wide range of hard and soft skills.

And in turn they gain from being in this sort of knowledge hub, he says.

"Leading universities - centres of excellence in their own dedicated and different fields of learning - sit next to each other, within arm's reach, offering unique cross-fertilisation opportunities," he says.

They are also a stone's throw from leading research facilities and blue chip organisations.

The latest addition, and the first from the UK, is University College London. The UCL Q campus will focus on conservation, museum studies and archaeology.

UCL Q intends to begin teaching postgraduate courses this year and relocate some research projects of relevance to the region.

Exporting experts

One obvious draw - in a time of financial cutbacks in the UK - is that the funding is being put up by Qatar Foundation and the kingdom's museums authority.

Professor Michael Worton, who co-ordinates UCL's global policies and strategies, insists that it is vital to the institution's reputation that standards be maintained.

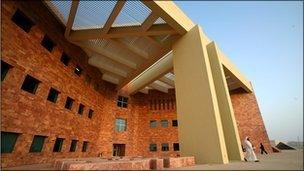

Liberal Arts and Science Building: Qatar is turning itself into a regional hub for higher education

He detects a shift in attitudes towards the purpose of higher education. This is partly from students who are more mobile, more demanding, more focused on employability.

And he says the interchange of ideas works both ways. For example, UCL is pioneering two-year masters degrees in another offshoot, its School of Energy and Resources in Adelaide, Australia.

"Building on what we have in London, but not just exporting it in some kind of imperialistic way, we're bringing our expertise in pedagogy, as well as our expertise in the discipline and creating something which is absolutely right for the environment in Australia or Qatar or wherever.

"One of my clear ideas is that things that we're doing overseas we would want to be feeding back in and saying 'look this works here, let's see how we can bring that in in the UK'."

Economic links

Such issues were debated last week at the Going Global conference in Hong Kong, organised by the British Council.

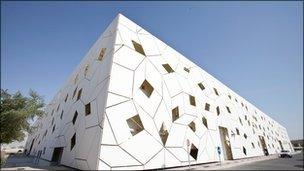

Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar - claimed as the first US medical school to set up overseas

The council's chief executive, Martin Davidson, says: "What is clear is that the strengthening link between economic development and international higher education is leading to a growing emphasis on regional and global collaboration."

He sees many opportunities for UK institutions to export their quality standards and to provide access to a UK qualification for a wider range of students - which incidentally side-steps the row about the issuing of visas to foreign students to travel to the UK itself.

It also provides greater flexibility and choice for students across the world who may not be able to afford to spend several years thousands of miles away from home.

Mr Davidson thinks it important for more British students to go abroad too, at least for part of their courses.

"In the long term, the United Kingdom's economic growth may be threatened if it fails to produce home-grown graduates who understand how to operate in a global market place," he says.

Competing hubs

The constraints imposed by quality thresholds have been observed by John O'Leary, author of the Top Universities Guide.

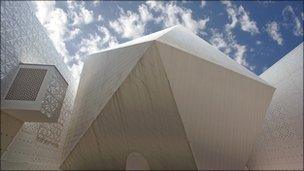

Game of two halves: Students in Carnegie Mellon's campus in Qatar

He says Education City is full of magnificent buildings, with quite small numbers of students.

"They may expand in time, but neither the universities nor Qatar want them to drop their standards so it's hard to see where large numbers are coming from."

Elsewhere things have not always gone smoothly.

"The host countries, quite reasonably, tend to apply quite a lot of conditions and there have already been some failures where the universities can't make a branch campus work," says Mr O'Leary.

"But Nottingham's campuses in Malaysia and China do well - largely, I think, because graduates get a Nottingham degree and the university uses its own staff."

India has plans to allow overseas universities to set up branch campuses. There is some scepticism about the likely extent of foreign involvement, but given the potential size of the student population, it is likely to draw interest.

"Apart from the Indian Institutes of Technology, none of their universities has made a mark on the world rankings, so you would think that branch campuses would attract a lot of well-qualified applicants as well as having a cheap base to do research," Mr O'Leary said.

And UCL's Michael Worton believes we are seeing an evolution of institutions into first regional, then global specialists - what he calls "mission specificity" - rather than providing a comprehensive range of courses for all students.

"We need to move away from an obsession with, if you like, the vertical hierarchy of international league tables and into much more of a horizontal landscape of diversity - and decide where we want to position ourselves," he says.

"To work out who are we and what are we trying to do, rather than everybody trying to do the same thing."