Paying for wind we don't use: How effective is wind?

- Published

Mike Hickey, manager of the Dinorwig power station, explains how the system works

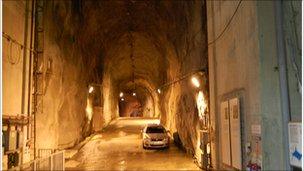

Deep inside an old slate quarry, near Bangor in North Wales, lies a possible solution to wind's problems.

It's a pumped storage plant - able to store excess electricity when the wind blows and release it when it stops.

The government's chief scientific adviser thinks we may need more of them to cope with rising wind supply.

Figures seen by the BBC suggest the National Grid spent more than £3m to compensate wind providers for energy that was not needed.

"The system works like a giant battery," says Mike Hickey, manager of the Dinorwig pumped storage plant.

When the wind blows and demand is light, it pumps water up the mountain into its reservoir.

As the wind falls, or demand rises, the price goes up - so Dinorwig's owners let the water flow back, generating power.

But schemes like this may only add to the cost of wind power.

Generous subsidies?

The UK government's ambition is to expand the current 1.3GW of offshore wind to a total of 33GW by 2020 at a cost of between £75bn and £100bn.

Some of this cost is passed on to bill payers.

An EU report into the European energy market, external looked at the effectiveness of subsidies across a range of countries.

It found subsidies for onshore wind in the UK in 2009 had been higher than for most other countries with large wind investments.

The reservoir above the Dinorwig pumped storage plant in Wales uses water as a giant battery

"The incentives that are paid in the UK for onshore wind and the average generation cost of wind, well, there is a big gap," said Dr Paolo Frankl, head of the renewable energy division at the IEA.

"In the UK, incentives for wind have been too high," he added.

There are also concerns over support for offshore wind.

In its most recent report,, external the Committee on Climate Change, which advises the government on wind power, suggested targets for offshore wind in 2020 could be relaxed to save money if other renewable sources were available.

"You would expect it to be more expensive and our analysis says it is significantly more expensive than onshore wind," said David Kennedy, the committee's chief executive.

Rising cost

Maintenance is one factor pushing up the cost of offshore wind

Analysts had thought that the cost of installing wind turbines would naturally fall as the technology matured.

But a report last year by the UK Energy Resource Centre, external found the reverse. The cost of building an offshore wind farm has doubled between 2003 and 2008.

Part of the rise can be explained by a weaker pound and more expensive steel.

But the report also blamed supply chain shortages and planning delays, as well as uncertainty over policy.

The coalition government is looking at reforming planning law for wind farms - especially offshore.

The Green Investment Bank may make money for wind projects available more cheaply.

There are also wider benefits to the economy.

Bond Offshore Helicopters is one example. The firm currently services the oil and gas industry, but sees offshore wind as an opportunity to expand.

"The way the wind farm industry is going, we hope to be a major player in support of it," says ground operations manager Graham Wildgoose.

Changeable weather

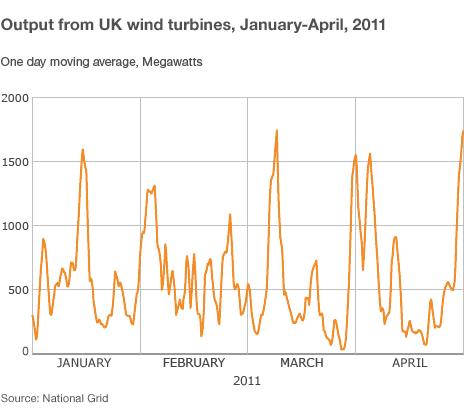

The wind rarely blows all year, so turbines produce only a limited percentage of their total capacity.

In the UK, wind turbines have typically produced at between 27% and 30% of their potential, in line with predictions.

However, in the last year there has been far less wind than normal and turbines have produced less electricity.

Research by the Renewable Energy Foundation, a charity which commissions research into the area and has been sceptical of wind power, found some onshore wind farms produced at less than 20% of their capacity.

The still weather meant wind's share of electricity supply only increased slightly in 2010 - to just 3.1%.

During a frosty, windless week in the depths of winter this year, the turbines almost stopped completely.

But later, on a warm, windy night in Scotland, there was plenty of wind available and relatively little demand.

Cost of uncertainty

During some of these nights the National Grid found it had too much electricity and was unable to move it south.

Figures produced by the Grid show that in May, it spent more than £2.6m paying wind providers not to produce electricity.

The Renewable Energy Foundation, which monitors the figures, says a further £1m was spent the previous month.

The money was used to compensate producers who were unable to sell electricity to the grid.

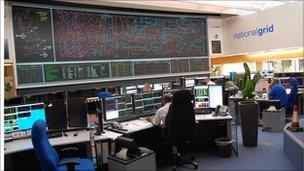

Workers at the National Grid balance supply and demand

The lines between England and Scotland need reinforcing and are sometimes down for rebuilding work.

REF says the payments show wind power is being installed too quickly.

"These things would never have been built if it wasn't for subsidy and now we're paying to chuck the stuff away," said John Constable, director of policy.

New solutions

Currently, the actual amount of electricity wasted is very small, as the grid turns off coal rather than waste wind.

But as we increase the amount of wind power on the grid, the problems will increase.

The government's chief scientific adviser on climate change, Professor David MacKay, says they are manageable.

"We will have to put in complimentary amounts of balancing services, which could be inter-connectors [with Europe], pumped storage, demand shifting [with smart grids] or mothballed gas power stations," he says.

The Dinorwig pumped storage plant was built in 1983 to act as a backup for nuclear power - new Dinorwigs could help balance wind.

Electric cars may also be used to store electricity and release it when the wind is low.

The independent Committee on Climate change says the measures are affordable.

Dinorwig has 16km of tunnels

"The economic analysis that we've done there suggests those costs are not prohibitive," says David Kennedy.

But research by energy consultants Poyry raised suggests investors may not be willing to pay for plants that only sell power when the wind isn't blowing.

"That would in turn lead to a lot of the system problems and potential blackouts that are so concerning consumers and their governments," says energy consultant James Cox.

The government is looking at changing how the energy market works in response to the worries.

Wind is clean and renewable, but it is proving far more complicated than many politicians may have imagined.

- Published1 June 2011

- Published8 June 2011

- Published9 June 2011

- Published27 May 2011