Alvin Hall: The generation poorer than their parents

- Published

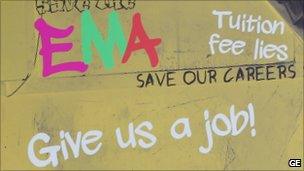

Thousands of young people have protested against rising tuition fees and poor job prospects

Many young people in Britain are set to be in a worse economic position than their parents, but is there any sympathy among older generations and is their cause gaining support from politicians?

"I'm 100% livid, I think that's the best way of putting it. We're going to get more angry than we are now."

Twenty-five-year-old City worker George Lewkowicz is mad about the economy.

He is typical of many young Brits under the age of 30 who have come to realise that their financial prospects are substantially less bright than that of their parents' generation.

When I first met George last year, he predicted young people would take to the streets - and he was proved right as thousands of students from across the UK protested against the rise in university tuition fees and the scrapping of the Educational Maintenance Allowance (EMA).

Today, George predicts this disquiet is only set to escalate:

"There is this huge population of older people who have essentially had it all, and my generation are then paying for their retirement."

When this dawns on people, George argues, "the riots will happen".

Pessimism

Shiv Malik, author of Jilted Generation - a book which examines the prospects for the 80s generation onwards - looks at his peers and sees further evidence of the impact a financially tight future is having on young people.

"From my middle-class cohort of friends - people who should be doing well - they're delaying having children, having families, settling down. They don't know what to do with their lives.

"They get personally depressed about this stuff, and it's a quiet depression that happens everyday.

"No-one is paying attention to it, and that's the most upsetting thing. The impacts are going to be huge."

Is the sense of pessimism that Shiv sees among his friends valid, or are young people just whining?

James Morris, pollster with Greenberg Quinlan Rosner and former speechwriter for Ed Miliband, says his research confirms Shiv's observation across generational lines.

British youth unemployment hit a record high in 2011 and commentators fear a "lost generation"

"If you ask people 'Is Britain going to be a better place to live in five years time?', the majority are saying no.

"If you ask older people... there's a consensus that this generation of teenagers, and particularly people in their 20s, are going to have a much harder time than their parents did."

However, Mr Morris makes an interesting qualification.

He says that while the dominant view among young people is that success requires effort, there is an important difference.

"If you look at my grandparents' generation, the kinds of hours they worked, the kind of work they did, the drudgery of [the] work... it's something young people today aren't minded to accept.

"They want a more interesting career. So there's a legitimate concern here that people's expectations about a decent job have changed."

Political priority

But what do the accused - the baby boomers - think?

James Morris says his research indicates that people in their 40s and 50s are the most pessimistic about the prospects for the younger generation - they are more worried about young people than young people are themselves. So does the older generation feel they have a responsibility to do something about it, too?

"They don't buy into that," say James.

George Osborne (left) and Ed Miliband have concerns over future generations' debt

"Baby boomers don't feel like their wealth should be taken away from them and moved to the younger generation.

"They feel the government ought to act to create the right sort of opportunities for younger people to move on."

Pollsters like James Morris see evidence of a gathering movement of support of the financial prospects of young people, and are advising the Labour Party that this is something people really care about.

And party leaders from across the political spectrum are responding by making this a real priority.

In the government's Spending Review announced last October, the Chancellor George Osborne put forward the case that "there is nothing fair about running huge budget deficits, and burdening future generations with the debts we ourselves are not prepared to pay".

Labour leader Ed Miliband is taking a slightly longer-term view. He talks about the "promise of Britain" - the expectation that next generations will do better than the last, whatever their birth or background.

He says he is worried that is being eroded.

Who will shout loudest?

There are also some signs of sympathy among the baby boomer generation. Angus Hanton, a baby boomer himself, has founded a new think-tank called The Intergenerational Foundation, external to lobby for fairness between the generations.

He sees clear culpability on the part of his older peers.

"Let's take my own house [which] I bought 16 years ago for £160,000. It's in south-east London. It's now worth about £1.15m.

"So I've gained a million pound windfall to which I do not feel entitled, and that windfall, at the moment, is tax-free. Were I to sell [the house], there's no tax on that gain."

"It may appear very lucky for me, but the reality is when I sell, it will probably be to a younger person who'll be getting a mortgage and spending most of their working life paying off that windfall which went to me. I don't think that's fair."

Angus Hanton recognises that people from across the generations face a tough financial future, but he offers a final observation that captures the bottom-line perspective for Britain's youth:

"We need to address consequent problems... but it's not fair to have a revolution where most of the victims are of a certain age."

On this the under-30s would definitely agree.

But with government spending being slashed, it is not just students who have taken to the streets in protest.

Just as young people may feel they have started to persuade the politicians and opinion formers about the seriousness of their plight, the generations before them are not sitting by quietly waiting to see what happens - as the recent pension protest in London showed.

One must wonder: since there are so many baby boomers in the UK - an estimated 12 million - will their protests drown out the voice of the disaffected youth?

Alvin Hall's Poorer Than Their Parents continues on BBC Radio 4 on Saturday 30 July at 1200 BST and Wednesday 3 August at 1500 BST. Listen again via the BBC iPlayer or by downloading the Money Box podcast.

- Published22 July 2011

- Published19 July 2011

- Published18 June 2011

- Published15 June 2011

- Published23 May 2011

- Published12 May 2011