Golf in Colombia aims beyond tourism to playing success

- Published

The morning sun rising over the greens of San Andres Golf Club, just outside Bogota, makes it easy to see why Colombia is increasingly using golf to promote itself internationally.

Meanwhile, from the tee of the first hole at Barranquilla's Country Club, golfers can savour the beautiful sight of the sun setting over the Caribbean.

The geographical diversity that makes Colombia unique is mirrored by the country's some 50 golf courses, and that's a powerful selling proposition.

"Here you can play golf next to the (Andes) mountain range, you can play next to the Caribbean Sea, next to a coffee plantation," says Maria Claudia Lacouture, the director of Colombia's tourism and investment promotion board, Proexport.

The country can also brag of several golf courses designed by some of the industry's big names.

And the authorities are trying to use this to attract more "corporate tourists", selling the country as a prime destination for seminars, congress and other events.

Reality v perception

The association with golf, however, is also meant to help change the country's international image, too readily associated with guerrillas and drug-trafficking violence.

"It is allowing Colombia to be recognised by its reality and not by its perception," Ms Lacouture says.

The reality of Colombia's golf courses, however, is that they are not easily accessible for everyone.

Golf is traditionally played in very exclusive private clubs and public facilities are rare.

Tourists can secure access through travel agencies, but for most Colombians that's not an option.

"We've got two or three public golf courses here, but still the green fees are expensive," says the president of the Colombian Federation of Golf, Lazaro Perez.

"For Colombians, if you pay 60,000 pesos, it's US$35 (£21), it's a lot of money," he explains.

More players

And that is certainly reflected in the number of golf players.

According to Mr Perez, in Colombia there are some 15,000 golfers that have official federation handicaps.

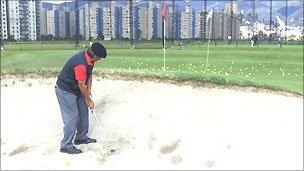

A pitch and putt course in central Bogota should encourage more Colombians to play golf

"But overall we could say some 35,000 people play golf in Colombia," he says.

While that is not a lot for a country with 46 million inhabitants, five years ago, the number of Colombian golfers was estimated to be just 20,000, which means the number has risen strongly during that period.

To a large extent, this is thanks to a public pitch and putt course and practice range opened by the golf federation in the centre of Bogota.

The facilities are quite accessible, both in the physical and monetary sense.

Raul Boada, a golf instructor, said this has made the sport accessible "to a lot of people who used to see it as something for the elite, for people with money".

Colombia has been looking to change its international image through golf

Sebastian Lopez, a 22-year-old who is honing his skills on the putting green, agrees.

"Here you see all kinds of people, from taxi drivers to high executives," says Mr Lopez, who is member of a private club based in the north of Bogota, but finds it difficult to go there on weekdays.

And by increasing the practice opportunities, the facility is also credited with helping to further improve the level of golf in a country already very competitive at the regional level.

Indeed, Colombian golfers are not strangers to good results, especially at the youth level.

"But once they go to college kids usually drop golf, to focus on their studies," says Mr Perez.

The promise of a PGA Latin American tour, however, could soon change that.

The aim of the federation is to get 40 Colombians professionals to play on the new circuit, which could start as soon as 2012.

US scholarships

Colombia has also been hosting several important international tournaments, including the PGA Nationwide and the European Challenge Tour.

Players like Mariajo Uribe are an inspiration to Colombian golfers

And the examples of professional Colombian golfers such as Camilo Villegas (number 37 in the official world rankings last year) and Mariajo Uribe, who plays both in the LPGA and European Tour, are a source of inspiration too.

Mr Perez says they also have some 70 youngsters studying in American universities, thanks to scholarships secured after US golf coaches came to watch them play in local tournaments.

But he knows that in order to take full advantage of all these opportunities, the federation has to look beyond the traditional Colombian golf base.

"That's why we have 200 kids from poor families taking golf lessons in the golf school set up by the federation," he says.

Whether they become professional golfers, or use golf as a stepping stone for another professional career, is yet to be seen.

But in this case, and by helping to attract tourists to the country, golf in Colombia seems to be starting to have an impact that goes well beyond the up-market clubs.