Notting Hill Carnival spirit boosts London's economy

- Published

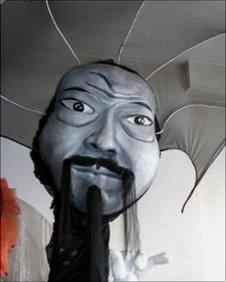

The Tiananmen Square puppet from 1989 shows Carnival's topicality

If you want to explore Notting Hill Carnival's cultural roots, a drab-looking shop in the west London district of Harlesden is a surprisingly good place to start.

The exterior of Mahogany Carnival Design may be plain, but as soon as you step through the door, a dazzling array of costumes and props meets the eye, with a tall, sinister puppet standing guard at the entrance.

"People called him Fu Manchu," laughs designer Clary Salandy, who runs Mahogany with her partner, structural engineer Michael Ramdeen.

Under its proper name, Shadow Over Tiananmen Square, the puppet was a highlight of Mahogany's first appearance as a "mas" band, or costume band, at the Notting Hill Carnival in 1989.

Like the carnival itself, both Clary and Michael have their origins in Trinidad, and they believe in maintaining the Caribbean island's tradition of topical social commentary on current events.

As Clary explains, she had already designed another set of costumes for the 1989 carnival when the Chinese authorities sent soldiers and tanks into Tiananmen Square to clear pro-democracy protesters, killing hundreds of people.

"I just had this vision of this great puppet that I wanted to make. I felt that the Caribbean needed to support its Chinese people," she says, referring to the sizeable Chinese communities in Trinidad and Jamaica.

"So I changed the whole design that year. He really did tower over the band and you could see him coming down the hill."

Carnival ambassadors

Mahogany, a limited company run as a not-for-profit social enterprise, derives its main funding from a £115,000-a-year Arts Council grant.

Clary Salandy has co-run Mahogany for more than two decades

But although its main motivation is artistic rather than commercial, its contribution to the business of Notting Hill Carnival should not be underestimated.

Unlike most carnival bands Mahogany operates all year round, providing costumes and shows for a wide range of events.

In the UK, its commissions have ranged from opera costumes at Glyndebourne to a live tableau recreating the Rose Window at St Albans Cathedral.

Mahogany's costumed dancers have also performed in other countries, including Nigeria, India and Singapore.

"We travel all over the world and they just want the spirit of Caribbean carnival in their event," says Clary.

As well as being international ambassadors for the carnival phenomenon, Mahogany's performers help to make Notting Hill Carnival a unique cultural product, more than simply Europe's largest street party.

Funding gap

As a worldwide event, only Rio de Janeiro's carnival in Brazil ranks ahead of Notting Hill in size.

According to the London Development Agency, it contributes up to £93m a year to the city's economy and supports the equivalent of 3,000 full-time jobs.

Young volunteers are keen to help assemble the carnival costumes

Visitors spend tens of millions of pounds buying food and drink from the carnival's 250 licensed trading sites, while music producers, clothing designers, merchandisers and security companies are among others who benefit.

The carnival also attracts an estimated 90,000 foreign tourists, who helped boost last year's attendance to more than a million.

But, unfortunately, "very little of that money finds its way back into carnival," as the event's co-director, Chris Boothman, laments.

In 2008, in an effort to avert a funding crisis, Mr Boothman and his fellow director, Ancil Barclay, took over the running of the event on a voluntary basis. It was meant to be an interim move, but three years later, they are still in charge.

As Mr Boothman explains, while the carnival offers the chance for entrepreneurs to make money, the central organisation gets by on volunteer effort and financial support from local authorities.

"Because it's a free, street-based event, the opportunities for generating income are extremely limited," he says. "In most countries that have anything like this, it's heavily funded by central government."

Brand 'exploited'

Apart from state funding, says Mr Boothman, another idea to bring in more money for Notting Hill Carnival is to adopt the model of the Edinburgh Festival.

This would allow organisers to charge admission to various events that could run alongside the free festivities - creating "a season of carnival, effectively".

Turning designs into actual costumes requires skill and effort

But one big drawback is that unlike, say, the Olympics, which jealously guards its branding, the Notting Hill Carnival has lost control of its intellectual property.

Mr Boothman points to unofficial carnival parties that use the name and brand, but make no contribution to the running costs of the event.

"Anyone can come along and say they're doing Notting Hill this and Notting Hill that. It's dispiriting when you can see people making lots of money and exploiting that."

Mr Boothman would like to be able to hand over to a core group of full-time staff, led by a festival director, a commercial director and an event manager.

But so far, there is no guarantee that the carnival will get the necessary funding.

"If it doesn't, the whole thing could possibly just fall over," he says. "I don't know how much longer it can continue in its present form."

Youth appeal

As the countdown to this year's carnival intensifies, Mahogany's three-storey building is abuzz with youngsters working on a voluntary basis to paint, glue and decorate dozens of costumes for the big day.

The larger costumes are too big for the premises and have to be assembled over the road in a nearby church hall.

Carnival headgear can fit even the smallest heads

In the wake of the riots that caused widespread destruction in various parts of London and other English cities, it is heartening to see how much the teams of teenagers, black and white, relish the chance for creative collaboration.

As Mahogany's promotional brochure says: "We are dedicated to helping underprivileged young people develop their skills and build greater confidence through the art of carnival."

Clary moves up and down the work benches, watching her designs take shape.

"Would you like to try on a hat?" she says to one little girl, the daughter of one of the older workers. "They're very tall, but the material's really light."

Clearly no-one is too young to get their first taste of carnival. Clary herself still has a trophy that she won in a carnival competition in Trinidad at the age of three. A picture of her in her prize-winning fairy costume is stuck to the wall, alongside press cuttings and other images of Mahogany's highlights as a band.

This year's theme is another last-minute decision by Clary, paying tribute to veteran Trinidad and Tobago carnival bandleader Wayne Berkeley, who died in June.

Notting Hill organisers have confirmed that the 2011 carnival will go ahead despite the riots. But another shadow is looming over this year's festivities - the spectre of high inflation.

Clary says the cost of the materials used to make her costumes is soaring. "Last year we might have bought something for £5, this year we're buying it for £15.

"Everything has increased. The insurance has gone up on the truck, the petrol has gone up. So in terms of the business of carnival, we're hitting a very difficult time."

- Published18 August 2011

- Published2 August 2011