Q&A: What is wrong with the housing market?

- Published

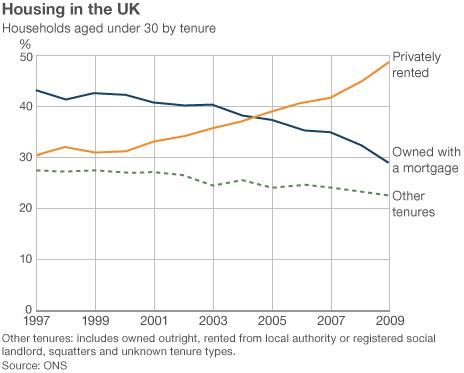

The balance between renting and buying in the UK property market may have changed permanently

Almost everything to do with the property market is a problem.

New house building is at a post-war low, with just 134,000 new homes built in the UK in 2010, government figures show.

That was the lowest number in any year since 1949, and just 31% of the peak number for building, which was 426,000 in 1968.

Mortgage lending to would-be buyers is being throttled by ultra-cautious lenders, so sales are less than half the number recorded in 2006, before the start of the international financial crisis.

Private rents are rising strongly and now average just over £700 a month in England and Wales, letting agents LSL say.

And property prices are still high and, in many parts of the UK, still out of reach of people on an average income, with average prices now standing at £204,981.

What is going on?

If house prices are "too expensive", why have they not fallen more?

Prices have been falling, but not by much.

They dropped by 2% in the year to June across the UK, according to the government's own house price survey, published by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG)., external

Despite mortgage lenders now demanding deposits typically worth 20-25% of a property's value, thus limiting the number of prospective buyers hunting for homes, prices seem remarkably resilient.

As BBC News explained in July, a number of factors are at play. The national picture is being distorted by the continuing prosperity of London, where most new job creation has been taking place.

In many places outside the capital, prices have indeed been falling.

Further falls have been reined back because some would-be sellers cannot afford to drop their prices, fearful that if they did so, it would erode the financial stake they have in their homes, limiting the deposit they could put down, thus making it hard or even impossible to move on.

Meanwhile, the UK population grew, external by 2.1 million to 61.8 million between 2001 and 2009, driven up by a more births than deaths and more immigration.

Crucially for housing demand, between 2001 and 2010 there was a rise of 1.5 million in the number of households, to 26 million.

So demand for homes, whether owned or rented, has been growing. And that has helped keep prices and rents higher than they would have been otherwise.

Why are not enough houses being built?

Some private house builders argue that the local authority planning system is too restrictive, stopping them building homes in reasonable locations.

Even if that were true, it would not explain the sharp downturn in house building in the past few years.

David Ritchie from Bovis Homes: "We're frustrated by the lack of support for first time buyers"

Last year, the number completed, external was just 60% of the number in 2007.

It is pretty obvious that the recession and continuing economic stagnation has had a big effect.

Builders are simply tailoring their output to the newly restricted demand of buyers.

And builders have also found it much more difficult to borrow from banks to finance their businesses.

It is also worth remembering that the building of council houses to let has almost died off, external.

The Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher started the process in 1979, when 86,000 local authority homes were built, down from 110,000 the previous year.

By 1990, that had fallen to just under 18,000 and by 1999, just 330 council homes were built. The nadir was the year 2004, when just 130 were completed.

In fact, since 1990, the building of "social" housing has been mainly the preserve of housing associations and since that year, they have built an average of 27,000 homes a year.

But that has not come anywhere close to the level of new local authority building seen in the 1960s, 1970s or even the early 1980s.

Are buy-to-let landlords making the situation worse?

Once upon a time, before World War II and even back in the 1950s, being a tenant of a landlord was a permanent way of life for millions of people living in rented rooms, bedsits and flats.

Ruth Patrick lives with her partner and says she is struggling to get onto the property ladder

The growth of home ownership, and council and housing association housing, saw the number of private rented homes shrink.

However, the past decade has seen the emergence of the buy-to-let (BTL) landlord and they are now a big part of the housing scene.

According to the Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML), of the 11.3 million mortgages in existence this year, 1.3 million had been taken out by BTL landlords.

By contrast, back in 2001, there were just 185,000 such mortgages in existence.

The result was that by 2008, the number of households renting in England from private landlords went back up from a low of 1.7 million in 1992 to just under 3 million.

Critics argue that the rapid growth of the BTL industry has simply crowded out many potential first-time buyers.

They also argue that the economics of the whole business are artificially rigged in favour of landlords, who can offset many of their costs, external, including mortgage interest payments, against their tax bills.

The counter-argument is that a large private-rented sector is a good thing, enabling people to move around without the relative hassle of selling and buying their homes, and providing a plentiful supply of rented homes for those who have no real interest in buying in the first place.

Another factor in the rising number of landlords has been the difficulty some people have had in selling their homes at a suitable price.

Rather than hang around, or sell at a rock-bottom price, they have let their homes to tenants instead, becoming perhaps temporary landlords, until the market changes and they can sell.

If there are so many more landlords around, why are rents rising?

With increasing numbers of people locked out of the house-buying market, and the population still growing, the balance of supply and demand has tipped firmly in favour of landlords.

LSL Property Services, which monitors private rents, says they have now risen for six months in a row and are now on average more than £1,000 a month in London.

In the spring, the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (Rics), external reported that would-be buyers, who were unable to buy a home, were increasingly moving into the rented sector.

With first-time buyers in particular unable to find enough mortgage finance, demand will continue to outstrip supply, Rics says, pushing rental levels even higher.

And in the longer term the UK property market could change radically.

"Home ownership in England has been falling since 2003 and has also fallen in the US, Australia, Austria, Finland and Ireland, to name just a few," says Andrew Heywood in an article written for Rics.

"If current trends were to be simply projected forward (always a dangerous game), then by 2025 home ownership could be below 60% - lower than most other European countries - while by as early as 2020, the private rented sector could well include more than 20% of all households."