What is quantitative easing and how will it affect you?

- Published

- comments

Quantitative easing aims to support the economy by encouraging people to save less and spend a bit more

The Bank of England has pumped hundreds of billions of pounds into the economy to support it through a series of shocks, through a process called 'quantitative easing'.

The economy now faces a different challenge - rapidly rising prices - and the Bank is starting to reverse that support.

So how does that work? And what effects will it have?

What is quantitative easing meant to do?

When economic times are hard, people worry about losing their jobs, and grow wary about spending money. Businesses see their customers staying away. They start losing money, and may have to lay off workers.

Normally, the Bank of England would try to make things better by cutting interest rates.

Lower rates mean you get less interest on your savings, so it's less attractive to save money than to spend it. And lower interest rates make it cheaper to borrow money, so it's easier to buy a new house, or car, or expand your business.

People buying things and businesses investing helps the economy stay healthy, protecting jobs.

But until recently interest rates were just above zero. There was no scope for another big cut.

That's why the Bank turned to quantitative easing (QE) as a way to encourage spending and investment.

How does QE work?

The Bank of England is in charge of the UK's money supply - how much money is in circulation in the economy.

That means it can create new money electronically. That's why QE is sometimes described as "printing money", but in fact no new physical bank notes are created.

The Bank spends most of this money buying government bonds.

Government bonds are a type of investment where you lend money to the government. In return, it promises to pay back a certain sum of money in the future, as well as interest in the meantime.

Buying billions of pounds' worth of bonds pushes the price up: when demand for anything increases, the price usually goes up too.

Many interest rates on loans offered by banks to businesses and individuals are affected by the price of government bonds.

If those government bond prices go up, the interest rates on those loans should go down - making it easier for people to borrow and spend money.

Will more QE make it easier to find a mortgage?

In addition, many investors buy government bonds in times of crisis, as a safe place to put their money, because the UK government has never failed to repay a bond.

If the Bank of England drives the price of those bonds up, that safety becomes more expensive.

So those investors may be encouraged to buy shares or lend money to businesses again instead - both of which will help to support the economy.

When did quantitative easing start?

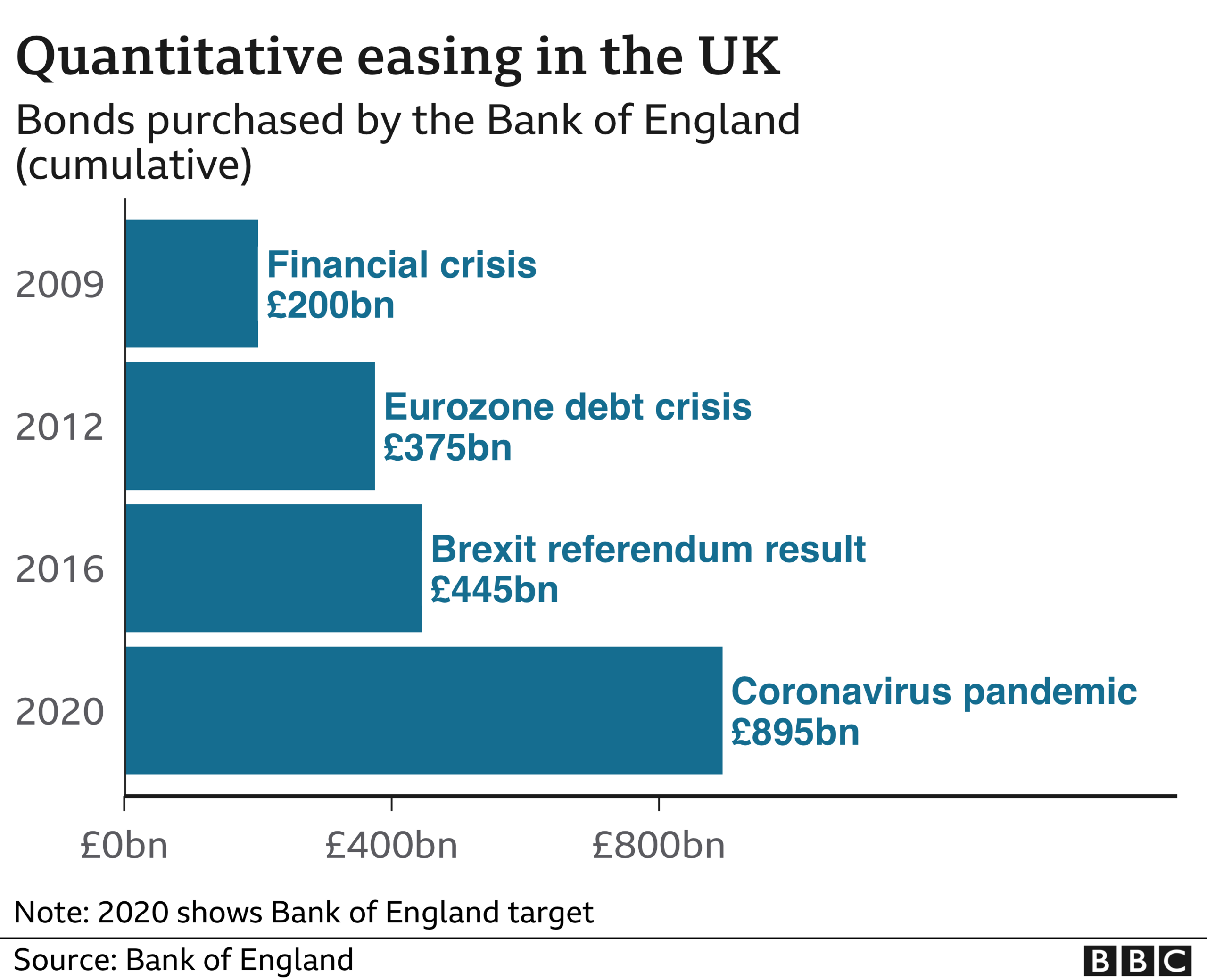

The first QE programme in the UK was launched in 2009 when the financial crisis was threatening the economy, unemployment was rising and the stock markets were in freefall.

The Bank subsequently launched new rounds of QE after the eurozone debt crisis, the Brexit referendum and the coronavirus pandemic.

A number of other countries started QE programmes after 2009, including the US, the eurozone and Japan.

Is the Bank now reversing QE?

Economies' recover from the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine sent prices rising fast.

That meant that instead of trying to support the economy, the Bank of England needed to slow it down to try to get prices rising less rapidly.

It did this by raising interest rates.

But in February 2022 it also began the process of reducing its holdings of government bonds as another part of the fight against inflation.

At first it let the holdings dwindle by not replacing any which the government repaid.

And at the start of November it became the first central bank among the G7 group of advanced economies to start actively selling bonds to investors.

This is sometimes known as 'quantitative tightening' as opposed to easing.

How does this affect government borrowing?

The Bank of England's QE programme helped the government to borrow money to cover the gap between what it raises in taxes and what it spends.

At the peak of the programme, the Bank of England held well over a third of the national debt.

And the government paid less interest on bonds owned by the Bank of England, external than other investors - which took further pressure off the public finances.

But bond prices are lower than they were when the Bank bought them, so it will make a loss when it sells them, which the government will pay.

And the unwinding of QE will make it more expensive for the government to borrow money.

What was the impact of QE?

Most research suggests that QE helped to keep economic growth stronger, wages higher, and unemployment lower than they would otherwise have been.

However, QE does have some complicated consequences.

As well as bonds, it increases the prices of things such as shares and property. This tends to benefit wealthier members of society who already own these things, as the Bank itself concluded in 2012, external.

Meanwhile, younger people found it harder to buy their first homes and build up savings.

Was it bad for pension funds?

Another important side effect of QE is the hit to pension funds. Government bond prices are used to estimate how much it will cost to provide pensions in the future.

If those bond prices go up, the cost of providing future pensions rises. As a result many firms were obliged to make bigger payments into their pension schemes, reducing money available to invest elsewhere.

And in many cases, QE will have contributed to the decision to close pension schemes altogether.

- Published5 November 2020

- Published4 February 2021

- Published19 March 2020