Bank of England boss pledges to do 'everything we can'

- Published

- comments

The governor of the Bank of England has vowed to do "everything we can" to support the economy amid a resurgence of Covid-19 cases.

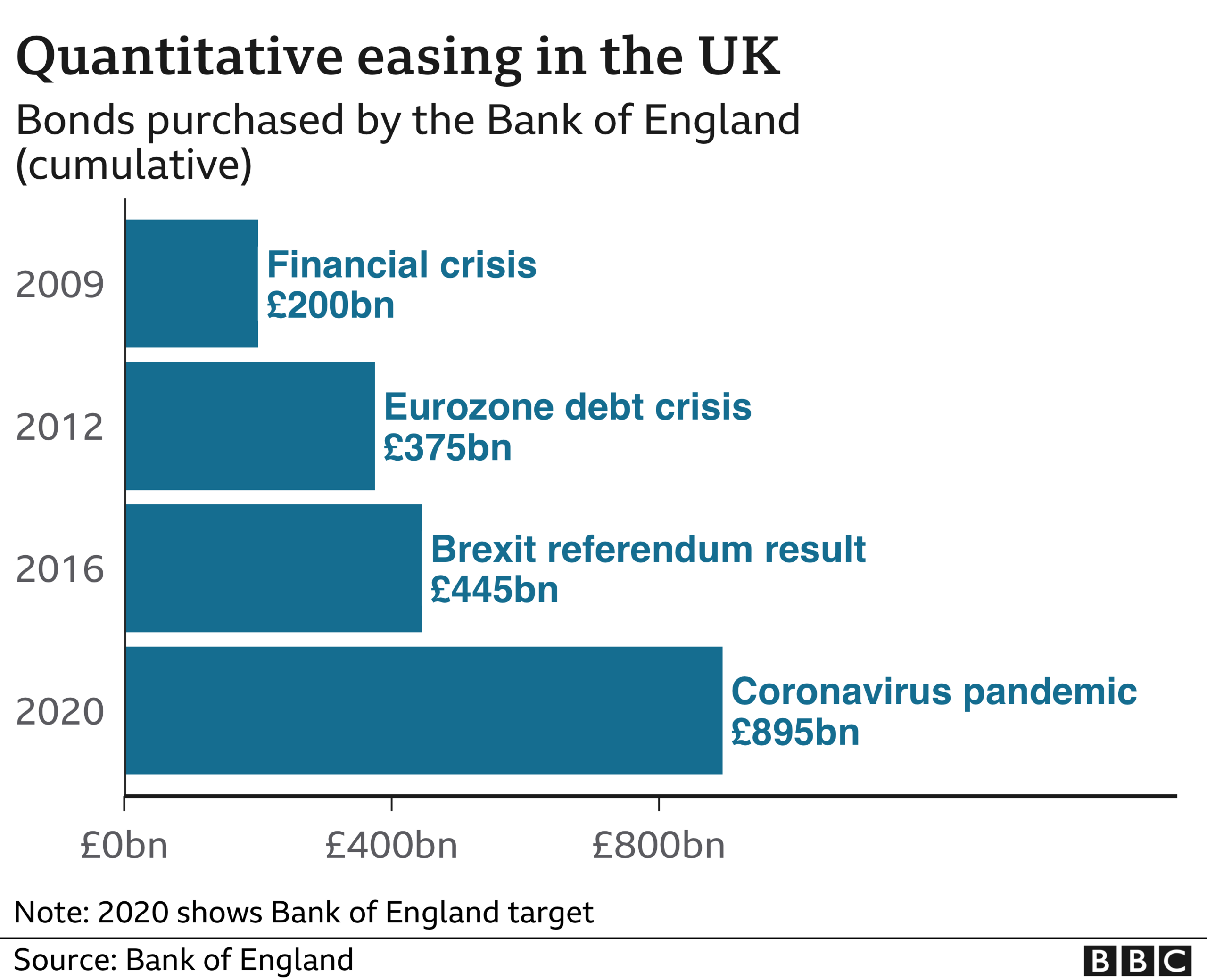

Andrew Bailey said it was important that policymakers acted "quickly and strongly", as the Bank announced a further £150bn of support.

Tighter lockdown rules, including new restrictions in England, are expected to lead to a slower, bumpier recovery.

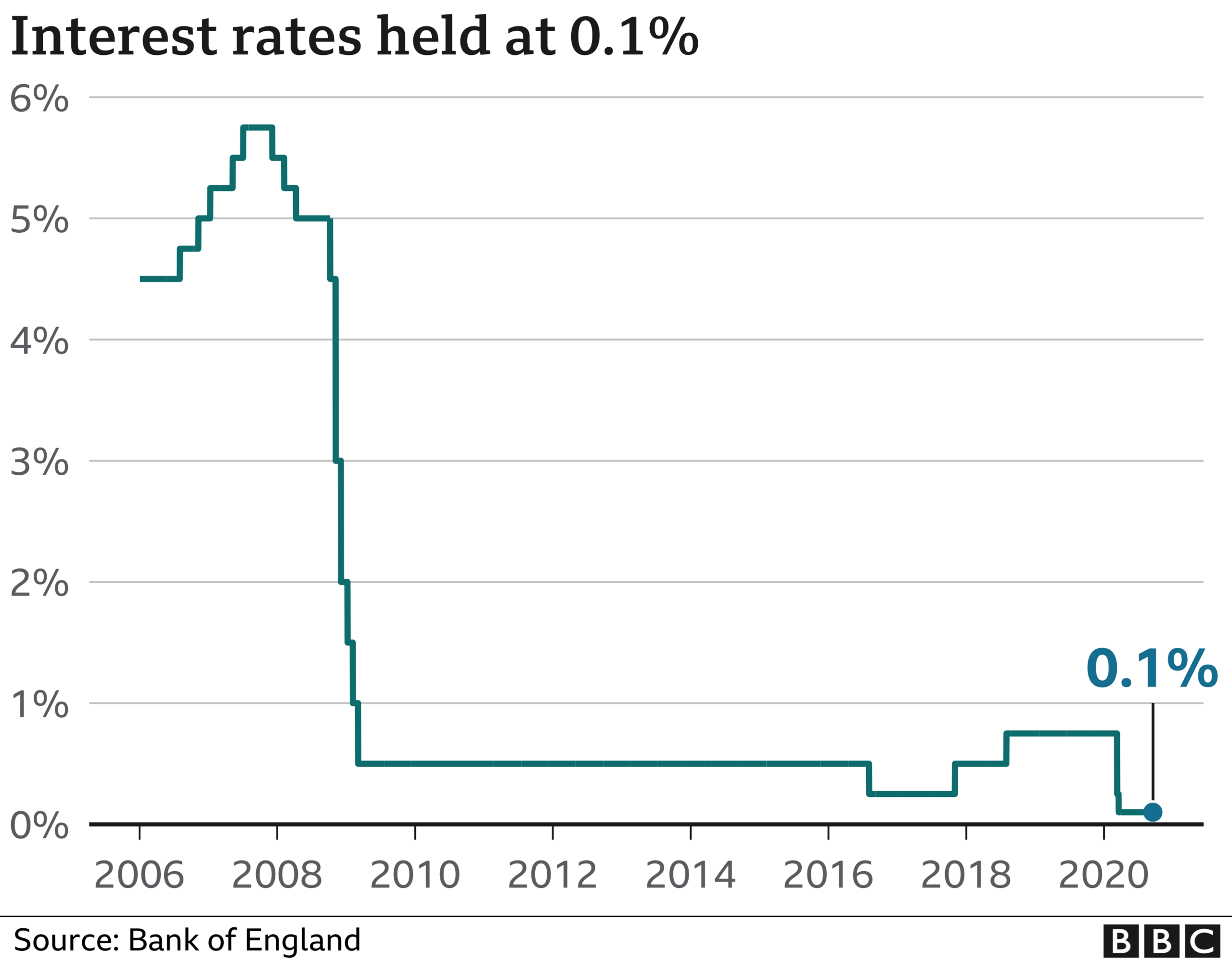

Policymakers also kept interest rates on hold at a record low of 0.1%.

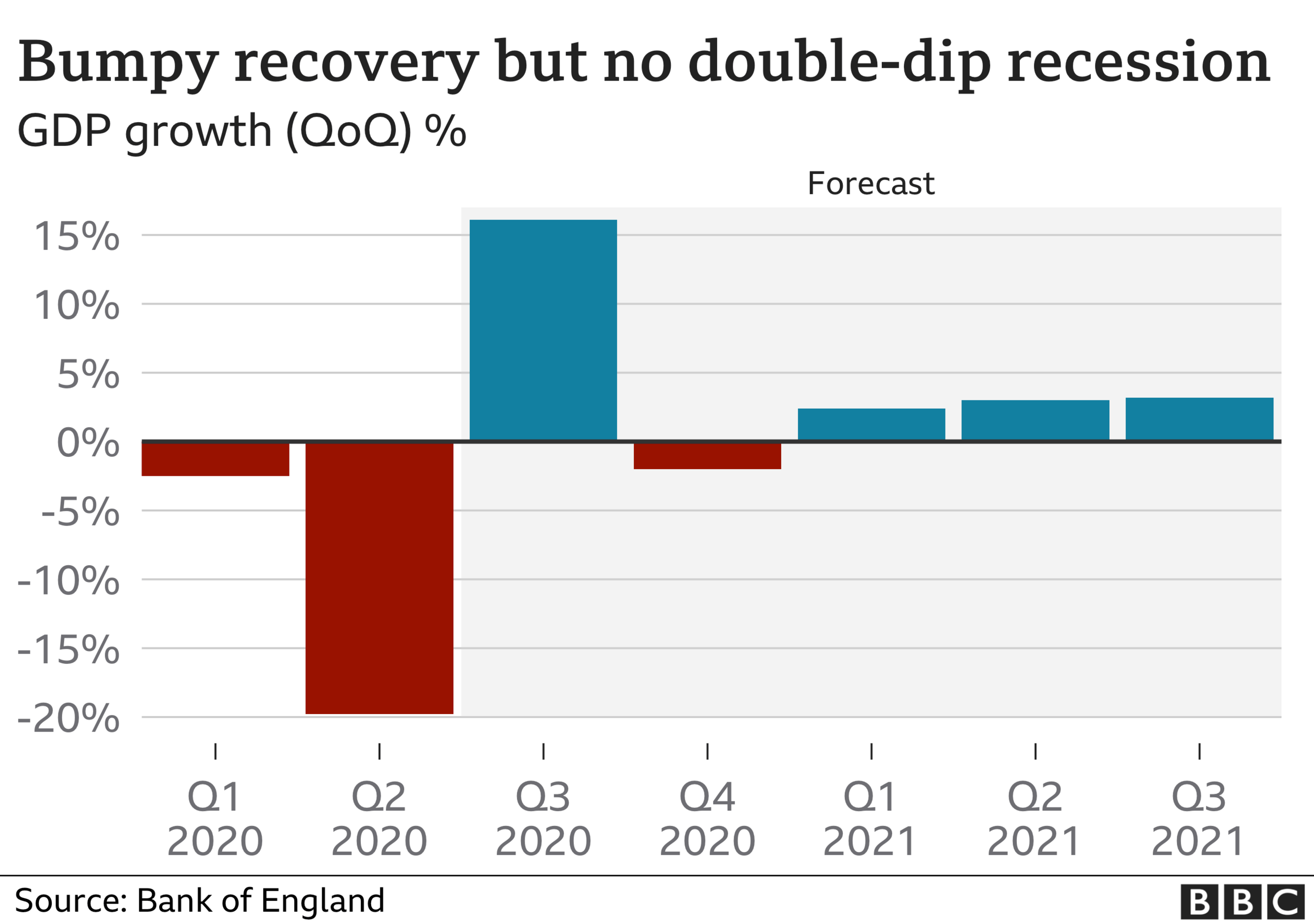

While the economy is expected to avoid another recession, the Bank believes unemployment will rise sharply as government support schemes wind down.

The Bank expects the economy to shrink by 2% in the final three months of 2020, before bouncing back at the start of 2021, assuming current restrictions loosen.

It does not expect the UK economy to get back to its pre-virus size until the following year.

Mr Bailey said: "We are here to do everything we can to support the people of this country - and we'll do it and will do it quickly."

How has the pandemic hit the UK economy?

The Covid-19 pandemic triggered the sharpest economic contraction on record earlier this year as nationwide restrictions were brought in to try to contain the virus.

Mr Bailey said the UK had not seen a similar disruption to economic activity in peacetime.

"Even then, these numbers are unprecedented in terms of the scale", he added.

Shoppers helped the economy to bounce back over the summer, and the Bank said retail sales remained strong.

Some people had started their Christmas shopping early, while others were buying furniture and household goods to adapt to working from home.

However, it said the hospitality, leisure, and tourism sectors had "suffered from lockdown rules", and many diners had stopped going to restaurants after the end of the Eat Out to Help Out scheme.

The Eat Out to Help out scheme announced by Rishi Sunak was popular with diners

Fresh restrictions across the UK are expected to drag on growth. The Bank expects the economy to shrink by 11% in 2020.

The UK is not predicted to sink into another technical recession - defined as two straight quarters of economic decline.

However, policymakers now see a deeper downturn and slower recovery than forecast in August.

What about the jobs market?

Hundreds of thousands of people have already lost their jobs amid the pandemic, despite various support packages, including an extended furlough scheme.

Redundancies have climbed to their highest level since 2009 in recent months.

The Bank expects unemployment to peak at 7.75% in the middle of next year, from 4.5% currently. This would be the highest rate since 2013.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak has announced that the furlough scheme - under which employees receive 80% of their wages for hours not worked - will now continue until March next year.

How does the Bank inject money into the economy?

The Bank of England is in charge of the UK's money supply - how much money is in circulation in the economy.

That means it can create new money electronically and the Bank spends most of this money buying government bonds through a process known as quantitative easing (QE).

QE is sometimes described as "printing money" but in fact no new physical bank notes are created.

Government bonds are a type of investment where you lend money to the government. In return, it promises to pay back a certain sum of money in the future, as well as interest in the meantime.

Buying billions of pounds' worth of bonds pushes the price up: when demand for anything increases, the price usually goes up too.

What about Brexit?

The Bank said Brexit remained a major source of uncertainty for businesses, as negotiations between the UK and EU on a new trade deal continue.

A survey by the Bank showed many large businesses were prepared for new trading rules.

However, it said even a smooth transition to a Canada-style deal with no tariffs on goods would knock a whole percentage point off growth in the first three months of 2021.

It said some shipments were likely to be "turned back at the border" for not having the right paperwork, weighing on export activity for the first six months of the year.

What are analysts saying?

Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said the Bank's economic forecasts looked optimistic.

"The MPC's forecasts have been updated for the new lockdown plans, but assume that the Covid hit to the economy gradually dissipates and that there is an immediate move to a free trade agreement with the EU in January; the risks to the outlook are skewed to the downside," he said.

The Bank is currently exploring if it can reduce interest rates below the current level of 0.1%.

It wrote to lenders in October to ask them how they would cope with negative rates. Commercial banks have until 12 November to respond.

Karen Ward, chief markets strategist at JP Morgan, said pushing interest rates into negative territory was the "direction of travel" for many central banks.

However, she expects High Street banks to shield savers from being charged.

"It tends to be large corporates that really face those negative interest rates," she said.

Are we heading for another recession?

While the Bank of England now expects the economy to contract in the fourth quarter of the year it was careful to say that, because this was just one quarter where the economy shrinks rather than two in a row, it didn't meet the rule of thumb for using the word "recession", where it shrinks for six months. So no double dip.

But before you say "Oh that's all right then," wait. The projection was that the economy would grow by 4% in the last three months of the year. Now it's expected to shrink by 2%. That's a 6% downgrade - almost as much as the peak-to-trough hit in the financial crisis. Over 2020 it will have shrunk by 11% - and won't get back to pre-Covid levels on the Bank's projections until 2022.

There's no official definition of the term "depression" and Andrew Bailey resists the term for its 1930s connotations. Informally though it's seen as a deep and prolonged recession where the economy shrinks by more than 10% - or lasts more than three years. On the former but not the latter criterion, our current economic predicament is indeed that bad.

- Published1 November 2022

- Published2 November 2020