Biomimicry: Beaks on trains and flipper-like turbines

- Published

Nature has been designing the world for billions of years

Since the dawn of time, nature has been working hard, engineering everyone and everything to the highest standards on Earth.

Dragonflies that can propel themselves in any direction, sharks with skin with tiny scales that help them swim faster, termites able to build dens that always keep a steady and comfortable temperature inside - those examples are just a drop in the ocean of amazing nature-designed solutions.

Granted, there have been a few individual attempts to copy nature's designs.

For instance, back in the 15th Century, Italian painter Leonardo da Vinci looked at birds' anatomy while sketching his "flying machine".

His device never took off, but the Wright brothers did manage to build the first aeroplane in 1903 - after years of observing pigeons.

Still, several decades had to pass before businesses began realising that nature could really help them too.

Probably one of the most notable nature-inspired technologies of the last century is the well-known hook-and-loop fastener, Velcro. The man who invented it, Swiss George de Mestral, is said to have been inspired by burrs he constantly removed from his dog's fur.

Innovation and copycats

But it wasn't until the late 20th Century, that many firms really started to devote time, money and often an entire team of designers, specifically charged with looking at biological solutions to technological hurdles they came across.

"It is important to look at nature - after all, it has had 3.8 billion years to come up with ideas," says Janine Benyus, a natural history writer who coined the term "biomimicry" in 1998.

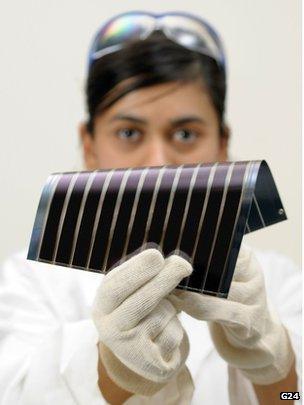

Solar cells that function just like leaves on a tree are a lot more efficient and can work even in low light

Ms Benyus was the first person to really describe this emerging science in her book Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature.

She says that after the book went viral, entrepreneurs from all over the world started calling her, seeking advice on resolving a particular issue in a non-traditional, nature-copying way.

So the world's first Biomimicry Institute was set up in 2005, with a team of consultants trained to help businesses.

"They come in, we learn what it is they're trying to do, and we look for that same function in the natural world - we do huge biological literature searches," says Ms Benyus.

"And then we say: 'Well, that's how nature has done it for 3.8 billion years!'

"And it's always a lot less energy, a lot less material, no toxins - a lot better."

Ms Benyus's clients range from Nasa to a multitude of companies of many different domains.

According to a well-known economist Lynn Reaser, on the global scale by 2025, biomimicry could affect about $1tn (£621 bn) of annual gross domestic product, and account for up to 1.6 million US jobs.

Butterfly's wings

"There are three types of biomimicry - one is copying form and shape, another is copying a process, like photosynthesis in a leaf, and the third is mimicking at an ecosystem's level, like building a nature-inspired city," says Ms Benyus.

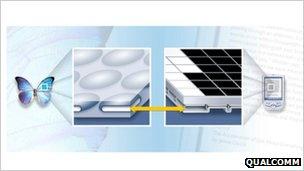

Businesses are usually interested in the first two categories, she adds - and a great example of the shape-based type is the Mirasol displays produced by a US mobile phone chip maker, Qualcomm.

Unlike regular screens with backlight or e-ink, these displays, which are still being developed, create colour by mimicking the way a butterfly's wings reflect sunlight.

Researchers mimic humpback whale's flippers to build turbine blades - but one day there could be biomimetic aeroplane wings, helicopter blades, ship rudders and propellers

The displays play video just like any other tablet or smartphone, but have a much longer battery life and softer-for-the-eyes effect of e-ink readers.

"The innovation has been inspired by the same natural principles that enable the reflective shimmer you see from a butterfly's wings or a peacock's feather," says Cheryl Goodman, senior marketing director of Qualcomm.

Qualcomm's mirasol displays imitate the way a butterfly's wings shimmer

She explains that all the displays need for illumination is ambient light, thus being "both low power and viewable in a variety of lighting environments, including direct sunlight".

The company says that the products are pretty much ready and just need some final touches before appearing on the market - with a number of firms already toying with idea of using them in their products.

Trains with beaks

Ms Benyus says that besides Qualcomm, many other companies call her team of consultants on a daily basis, asking them to sift through the lengthy archive of our planet's extensive history.

She lists just a few examples.

For instance, a Canadian firm Whalepower mimics humpback whale flippers and uses the principle on wind turbines and fans, reducing the drag and increasing the lift.

A paint company Lotusan applies the lotus effect, mimicking the shape of the bump on a lotus leaf.

Lotus leaves are self-cleaning - they have tiny bumps that help remove the dirt when it rains.

Lodafen uses the principle in architecture designs - and in Europe, there are more than 350,000 buildings that have this kind of paint.

The design of the high-speed Shinkansen bullet train in Japan was inspired by the beak of a kingfisher

"And of course the high-speed train, Shinkansen bullet train in Japan - instead of having a rounded front, it has something that looks like a beak of a kingfisher, a bird that goes from air to water, one density of medium to another," she adds.

"So as the train enters a tunnel, it's quieter because there is no pressure wave as with ordinary trains; and it uses 15% less electricity, too."

Leaves and solar cells

She pauses momentarily, and then goes on to describe in detail a process-based type of biomimicry - solar cells that copy the natural process of photosynthesis, or creating energy from sunlight, in leaves.

When Professor Michael Graetzel from the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne in Switzerland applied it to solar cells, he won the 2010 Millennium Prize.

He called his creation a dye-sensitized solar cell, or DSSC.

The main difference from a traditional solar cell is that DSSC does not require high-energy consuming silicon, but is instead made of titanium dioxide, used in white paint and toothpaste.

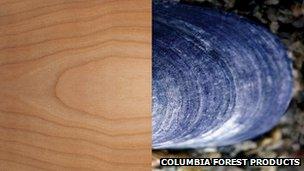

Plywood made by Columbia Forest Products uses an adhesive called purebond - inspired by adhesives made by blue mussels

The dye in cells absorbs light just like chlorophyll in photosynthesis, releasing an electron that is conducted by the chemical electrolyte in the cell.

And while silicon solar cells require direct sunlight to generate electricity, DSSC uses any light, and works even in very low light conditions indoors or outdoors, and regardless of the panel's orientation.

It can then power a broad range of electronic devices such as remote controls, wireless keyboards, mobile phones, e-readers, and much more.

"Nature possesses infinite patience in developing and perfecting processes, including those to produce energy such photosynthesis, and by mimicking and adapting [them] we can develop technology that is useful, low cost and aligns to our fragile environment," says Marc Thomas, CEO of Dyesol Inc., the company that makes the cells.

Colliding birds

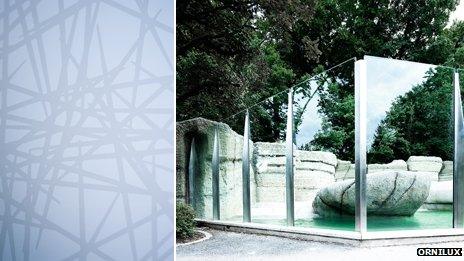

Glass is a well-known hazard for birds, continues Ms Benyus.

On the left is how a bird would see the glass - which looks absolutely transparent to humans

A US glass maker Ornilux decided to tackle this problem by observing spiders.

Certain species of spiders, in particular the Orb Weaver, have certain ultraviolet-reflective materials in their webs' silk, to warn birds about the web's presence.

Birds may not see a regular web, but they spot UV-reflective materials very clearly, thus avoiding destroying the web and the spider's prey.

"It is the reflective and transparent properties of glass that make it dangerous for birds," says Lisa Welch of Ornilux.

"Birds do not 'see' the glass, but instead respond to reflections of sky and vegetation on the glass, seeing a tree to land on or a flight path to the sky.

"The way to make glass visible to birds is to create visual markers on the glass, alerting them to the presence of a solid object."

Using UV-reflective materials on the glass was a solution - the window stays transparent to people, but not to birds.

A number of buildings around Europe and North America now sport this ingenious glass, possibly saving many birds' lives.

"I'm sure all of the answers to what we are wanting to solve exist in some form or another, in nature," says Ms Welch.

"Inherently, nature provides balanced, symbiotic solutions.

"Human beings have demonstrated a terrible track record of maintaining environmental balance in trying to solve 'problems'.

"So copying nature may just be the way to go."

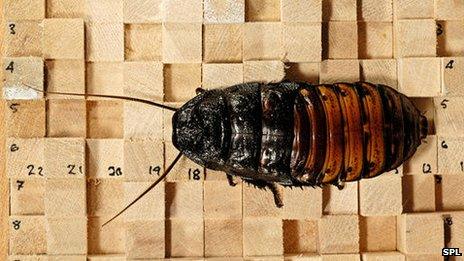

Scientists study insects in order to mimic their locomotion and build insect-like robots