UK government's Green Deal to cut fuel bills

- Published

As bills rise and green subsidies are cut, politicians are looking for ways to reduce our bills - and emissions - at no cost.

The government's solution is insulating buildings - saving money and even creating jobs to do the work.

But insulation is expensive to put in. The government hopes its "Green Deal" will encourage private investors to offer cheap loans for the work.

But will the carrot work or is a stick - and some state money - also needed?

State support for energy efficiency measures to help cut bills will not increase significantly.

Instead, everything depends on consumers wanting to borrow money, and lenders wanting to give it to us.

The government wants 14 million households to sign up by 2020 - involving up to £100bn and creating up to 65,000 jobs by 2015.

"We don't know if the financial mechanism will work, there may be an analogy to the sub-prime mortgage situation," warns Ian Preston, from the Centre for Sustainable Energy.

Cash for insulation

UK households consume more energy than most of our European neighbours because our homes have not been built to the same standards.

Sarah Harrison shows the BBC around her eco-home

Changing that requires retro-fitting homes to stop draughts and heat loss.

Improving efficiency is also important in meeting the government's climate targets. Some changes, such as new lightbulbs, are cheap, but insulation can cost thousands.

So the government wants to entice private investors to offer up to £10,000 a household as a loan - paid back through savings on energy bills.

The loan would come with a promise that consumers would save money on their bills, including repayments.

And the debt would be tied to the home and its energy bill - not the owner or occupier.

In effect, the government says, we'd be able to insulate our homes for free.

"People can insulate their homes, save money, at no upfront cost," said Nick Clegg, Deputy Prime Minister, launching the Green Deal.

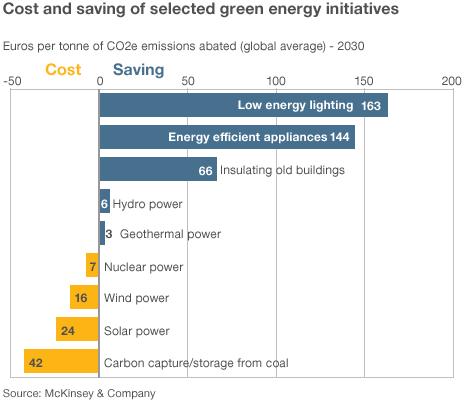

It is a logic backed by consultants McKinsey and Company, which has conducted research showing that some green measures, such as insulation, can save money and so balance the cost of others, such as solar.

Despite that, some measures, such as new boilers, may still end up costing money - and some fuel-poor homes may simply use any savings to heat their home adequately.

To pay for this, the government is levying a charge on our bills to top up the deal.

Though the government scheme will not start until late next year, some companies, including The Carbon Trust and British Gas, have already started rolling out similar schemes aimed at homes and businesses.

Consultants PricewaterhouseCoopers have worked on a way of financing the proposal by packaging up loans to consumers and selling them to investors - as happens with mortgages. The idea is to reduce the cost of the loan.

But what if the loans are not paid back?

The problem, says Sam Arie, a visiting fellow at Oxford University's Smith School of Enterprise & the Environment, is that only the less well-off are likely to take out a Green Deal loan. Richer households, who also use more energy, will pay themselves.

"That part of the housing stock is mostly owner-occupied, and they mostly have mortgages, and if they don't they have savings."

The government wants us to borrow money to cut our fuel bills

"We're creating a scheme in which the quality of the loans will not be scrutinised, in which we could lose money if they are not paid back," he says.

There is also a risk that the loan will make it harder to sell a home.

Consumer Focus asked homebuyers how they would react to a Green Deal loan sitting on a property they were looking to buy.

"Both buyers and tenants said that could put them off choosing that property," said Liz Lainely, policy manager at the charity.

And recent research from the Centre for Sustainable Energy found that, on average, we used only two-thirds of the energy the government assessment would have expected - meaning it would take even longer to pay back the cost of new energy saving measures.

To overcome such concerns, some argue the government needs to impose costs on those who do not make their homes energy efficient - or simply put up the cost of energy for heavy users.

"Nobody suggests that the solution to alcohol addiction is to subsidise the price of fruit juice, you have to have strong targeted messages to people who overconsume and discourage consumption," says Mr Arie.