Italy: Nearer the precipice

- Published

- comments

It is getting messier for Italy.

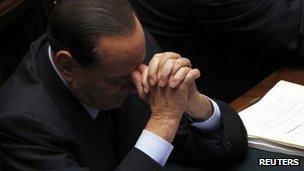

In spite of Silvio Berlusconi doing what many investors wanted - announcing he will stand down as premier - the implicit price that Italy has to pay to borrow has risen again, nearer to dangerously unaffordable rates.

This morning the interest rate - the yield - on one year loans to the Italian government rose from 6.4% to 6.63%, and there was a rather smaller rise to 6.79% in the rate on 10-year loans or bonds (before a slight retreat back to 6.76%).

These are (again) euro era highs for these implicit interest rates - very worrying for a government with more than 1.8 trillion euros of debt (and see my earlier note for more on the damaging financial impact of such yield increases).

What this means is that the cost for Italy of borrowing is becoming dangerously close to the 7% threshold, which the precedent of Ireland, Portugal and Greece suggests would mean that Italy would be unable to avoid an official rescue.

To put it in simple terms, if Italy had to pay an average interest rate of 7% on the whole of its debt - which would only happen over years, since it borrows at fixed rates for fixed periods - that would add a crippling 70bn euros to its annual interest bill.

Megan Greene: The only realistic game-changer is for the ECB to step in

The subtler, more important point, is that when the implicit interest rate rises to that kind of level, investors know that a country with big debts can't afford to repay what it owes, so they stop lending to said country, they go on strike. No one wants to lend to a country when that country would use the loan to pay the interest on previous loans - that's throwing good money after bad.

To state the obvious, a lenders' strike would be lethal for a country like Italy, which has to borrow 362bn euros next year (according to Bloomberg data) simply to pay interest and existing debts falling due.

So what's the specific reason this morning for the spike in Italy's implicit interest rate?

Well it is because the organisation through which investors clear or settle their bond transactions, LCH.Clearnet, has announced that those trading in Italian bonds have to deposit more cash with it to cover the risks of non-payment.

In essence, it means that LCH.Clearnet has decided that the risks of trading in Italian government debt have increased. And the important point is that by insisting that those trading in the bonds put up more "margin", that they deposit more cash with LCH.Clearnet to cover the risks, LCH.Clearnet has made it more expensive to trade in Italian debt.

That is this morning's explanation for why the price of that debt has fallen and the yield or implicit interest rate on it has risen.

The increase in the margin, or deposits required, is significant. For 10-year bonds, it has gone up from 6.65% of the sum trade to 11.65%, a rise of 75%.

For one-year loans, the increase is even bigger, in proportionate terms, from 2.45% to 6.45%.

LCH.Clearnet has taken the action in part because the gap has widened between the yield on Italian bonds and the yield on a basket of sovereign AAA bonds (ie government debt that has the highest credit rating).

What it all shows is that Italy's financial woes are unlikely to be solved in the short term by when and whether a new government is formed in Rome.

Investors need to see that the eurozone has the resources to lend to Italy in the event that no one else will. And right now they've noticed that progress on expanding the European Financial Stability Facility, the bailout fund, is painfully slow.

I am told it will be weeks or months before we can be confident that the resources of this fund have been increased from 440bn euros to a trillion euros. The technical work on this is, according to an official, is proving to be painfully slow.

And, as readers of this column know, there are plenty of investors who believe that a trillion euros is anyway about half what's required to persuade them that the eurozone really has the muscle to prevent Italy sliding to default.

Update 09:57: The yield on the Italian 10-year bond has now risen through the 7% level that precedent suggests means Italy will have to seek emergency funds from the eurozone.

The problem, as I said earlier, is that right now there is not enough in the kitty of the bailout fund, the European Financial Stability Facility, with only around 250bn euros left, of the original 440bn euros.

So this is a serious crisis.

I am told that the chief executive of the fund, Klaus Regling, is due to produce proposals in the next week or two to increase the firepower of the fund to 1 trillion euros or so - by using its resources to guarantee or insure loans.

Will markets give him a week or two to come up with the plan? That does not look likely right now.

Update 10:04: There has also been a remarkable inversion in the Italian debt yield curve, with Italian bonds of shorter maturity - including 1-year loans - all yielding more than 7% now.

This shows that investors believe that short-term risks of holding Italian debt have risen quite considerably.