Have taxpayers got a decent deal on the Northern Rock sale?

- Published

- comments

A bird in the hand, worth two in the bush?

It is possible to argue that taxpayers have got a reasonable deal on the sale of Northern Rock.

Here is how that argument would work.

The Treasury injected £1.4bn of capital into the bank. But by the end of this year - when the sale to Virgin Money is supposed to be completed - that capital will have been depleted to around £1bn.

The reason the capital has been eroded is that Northern Rock is lossmaking. This is because, in the act of cleaning up the bank, it retained the overheads of 75 branches, a call centre, and management, plus deposits of £16bn, versus mortgages of just £14bn.

Or to put it another way, the interest received on the mortgage book is dwarfed by all the other costs, including interest paid on deposits. So the Rock makes an intractable loss.

What that means is that Virgin is paying £747m in cash, plus - if all goes well - a possible further £280m for a bank that by December 31 will be left with net capital of around £1bn or maybe a bit more.

Depending on what assumptions you make about how much of the deferred purchase price will ever be paid, Virgin is probably paying a discount of around 20% to the book value of the Rock.

Now that compares very favourably with the market value of our biggest banks, whose shares are currently trading at discounts of between 40% and 50% relative to net asset vaue.

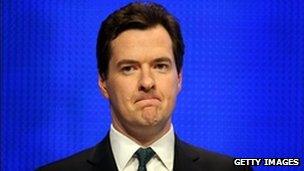

On that basis, George Osborne hasn't done too badly in the deal.

The question is whether he could have done better - as the shadow chancellor Ed Balls has suggested - by waiting.

What perhaps is most interesting is that the Chancellor has decided to crystallise the loss now, rather than suspend the sale in the hope that markets recover enough to break even on the deal.

His decision to take this bird in the hand may be seen as George Osborne placing quite a big bet that markets and economy are going to get worse before they get better.

Harking back to the question I posed at the end of my last post, the Rock sale could therefore be seen as a harbinger of eurozone meltdown - just as its collapse in 2007 marked, for many, the beginning of the original credit crunch.