Don't mention the R word

- Published

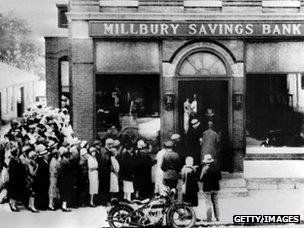

Western governments used to think that financial panics were a problem of the distant past

R is for run. As in bank run.

If you're wondering what a bank run is, think of Northern Rock, external. It is a sensitive topic, not least here at the BBC, external.

But it is a subject that is being increasingly discussed by investors and economists in the eurozone. One can assume it is also being discussed in private by European policymakers too.

Because the fact is that Europe's banks already face what amounts to a slow-motion run by big institutional investors.

They're not queuing up at branches. Instead they are withholding their money at the click of a mouse.

Major US money managers and lenders are pulling out of the eurozone, as is clear from the cost to eurozone banks of borrowing in dollars right now, which has returned to extreme levels last seen during the global financial crisis, external.

Moreover, data from the European Central Bank (ECB) suggest that Europe's banks themselves are losing confidence in each other - though not yet quite as badly as in 2008.

They have increasingly been putting their cash in the safe hands of the central bank, rather than lending it to each other, despite the punitively low interest rate the ECB pays them.

Lessons learned

To be clear, there is no immediate risk of banks running out of cash.

Greece is at the forefront of the crisis: Deposits at the country's banks have fallen 21% since January 2010, according to Greek central bank data.

But the Greek banks have been on ECB life support for over a year now, and they have duly paid out every cent that has been demanded from them.

They borrow the money from the central bank by providing Greek government bonds (ie loans they have made to their government) as collateral - just as you would offer your house as collateral to take out a mortgage.

How is the European Central Bank helping the banks?

And the ECB has continued to provide cash to the Greek banks even as that collateral has become increasingly worthless - leaving the ECB exposed to big losses if Greece stops repaying its debts.

As Greece's credit rating has been cut and cut by the big three ratings agencies, so the ECB has lowered and lowered the minimum standard of collateral it is willing to accept, because it is determined to keep the Greek banks alive.

The ECB has learned the lesson of 2008 - which is that if one big financial institution is allowed to fail, then panicky lenders will pull the rug from under the entire financial system.

Indeed, before the global financial crisis, Western governments thought that such panics had been laid to rest decades ago.

After the bank runs of the 1930s, US and European governments instituted two important changes to make sure they were never repeated.

Firstly, the central bank agreed to act as "lender of last resort". That meant that - so long as a bank was fundamentally sound - the central bank would always lend it cash to stave off a panic, just as the ECB is doing now.

Secondly, the bank accounts of ordinary depositors like you or me were guaranteed by the banks' respective governments. So that even if a bank goes bust, ordinary folk do not need to worry about losing their savings.

That formal guarantee currently amounts to 100,000 euros (£86,000; $133,000) in eurozone countries.

What governments did not do was to guarantee the multi-million deposits of institutions such as money managers, big companies or other banks. These investors were supposed to be sophisticated enough to bear their own risk.

But by 2008, banks had become so dependent on the money they got from these large depositors (and they still are), that governments in effect had to extend their guarantee to cover these investors too, or else face another 1930s-style financial meltdown and depression.

Incredible guarantees

That's why the ECB is currently pulling out all the stops to keep Europe's banks afloat.

And it's also why Europe's governments have promised to pour even more money into recapitalising their banks - which basically means taxpayers will provide a buffer to absorb the banks' losses.

But, if their money is effectively guaranteed these days, why are the big institutional depositors in the eurozone's banks still losing their nerve?

The reason, it appears, is that they no longer fully believe in the guarantee.

Greece is the most extreme example.

It is widely accepted that the country will never repay its debts. The only question is whether it will negotiate a write-off of much of its debts by its lenders, or just thumb its nose and stop repaying them.

But if Greece cannot pay its debts, how much is its guarantee of the Greek banks worth?

What's more, Greece's biggest lenders are - unsurprisingly - none other than the Greek banks themselves.

So even if Greece manages to agree a significant write-off of its debts, it will then have to bail out the biggest losers - its own banks. In effect, it would be stealing money from its own pocket.

Nonetheless, if the Greek banks really did go belly-up, would the Greek government let the savings of its own citizens be wiped out?

Almost certainly not. As the case of the UK's Northern Rock amply demonstrated, governments will always put the money of their own voters first.

Which means that all the burden of loss would fall on the banks' other lenders - which is one of the things that is making those other lenders so nervous.

Playing Argentina?

There is, of course, an alternative scenario. Greece could leave the euro - a possibility openly discussed by eurozone leaders these days.

On the plus side, Greece's debts would be converted into drachmas, meaning the government could rely on the newly independent Greek central bank to print all the cash it needs to repay them - although if it actually did this, it would probably cause massive inflation.

The deposits at Greek banks would also be converted into drachmas. So there should be no question of the government honouring its guarantee of people's bank accounts in drachmas.

But here is the big problem. Who on earth would want their savings to be converted into a new currency that would then very likely lose much of its value against the euro?

The large institutional depositors at Greece's banks certainly wouldn't.

Which raises the question, if people start to think that a Greek exit from the euro is inevitable, would ordinary Greeks also start to exercise their right to convert their deposits into euro cash, external, or - more prudently - to transfer their deposits to a newly-opened account in Germany?

And this is where it gets nasty.

Because big investors fear that, in a worst-case scenario, Greece might decide to "do an Argentina" - that is, to stop paying its debts, unhitch and devalue its currency, and blow a raspberry at the rest of the world, like Argentina did in 2001-02.

In which case the government may have a perverse incentive to permit a run on its own banks.

Why? Because when a Greek closes his or her account in Athens, their bank turns to the Greek central bank for the money.

Then, depending on the depositor's request, the Greek central bank either prints the banknotes needed, or - through the system of central banks inside the eurozone - borrows the money from the Bundesbank, Germany's central bank.

Either way, as depositors' money flows out of Greece's banks, the Greek central bank ends up becoming more and more indebted to the European Central Bank.

And if the Greek government has secretly decided to renege on its debts, then why not let its citizens do what they must to preserve the value of their savings ahead of the big announcement?

Speaking volumes

What does all this mean for the much bigger eurozone economies - Italy, Spain, France and even Germany?

Greece is small, and the losses to the rest of Europe from a Greek implosion may be manageable. What may not be manageable is the precedent it would set.

First of all, many other eurozone economies share characteristics with Greece. They have too much debt (considering government and private sector debt together), and in the case of southern Europe, their economies are fundamentally uncompetitive.

That means they face little prospect of the strong economic recovery that may be needed to make their debts repayable. Indeed, the current financial crisis appears to be plunging Europe back into recession.

Secondly, Europe's banks may not be too-big-to-fail, so much as too-big-to-rescue. This is the big concern hanging over France - can the country actually afford to prop up the French banks that have lent so much to Italy and Spain?

Thirdly, a failure in Greece will speak volumes about the lack of political will to solve the eurozone's problems.

Germany has refused to put more of its taxpayers' money on the line to prop up fellow eurozone governments, somehow imagining that China would be willing to do this instead.

The Germans fear that if they go easy on southern Europe, it will just encourage more profligacy, and they will be left carrying the can.

For similar reasons, the ECB - under the Bundesbank's influence - has likewise refused to print the trillions of euros needed to bail out Europe's struggling governments.

It has also refused to even consider tolerating a higher inflation rate - something that many economists warn will be needed to make Europe's debts repayable, and to help southern European workers regain a competitive edge.

Lastly, and most worryingly, is that panic is highly infectious. Once depositor bank runs start in one place, they have a worrying tendency to spread quickly to other places.

That was the biggest lesson of the 1930s bank runs, and one that the world thought it had learned.