Resource depletion: Opportunity or looming catastrophe?

- Published

We will need to produce 70% more food by 2050 to meet the demands of the world's massively expanding population, according to the United Nations

Imagine a world of spiralling food prices, water shortages and soaring energy costs.

For many living in the world today, this nightmare scenario is already a reality. Even for the well-off living in developed economies, it's becoming all too familiar.

And on current projections, it's going to get a whole lot worse. Short-term fluctuations in supply and demand aside, a global population explosion combined with finite resources means the planet cannot sustain ever-increasing levels of consumption using current models of production.

And there isn't much time to do something about it.

"The challenge we are facing over the next 20 years is unprecedented," says Fraser Thompson, senior fellow at the McKinsey Global Institute.

Exploding population

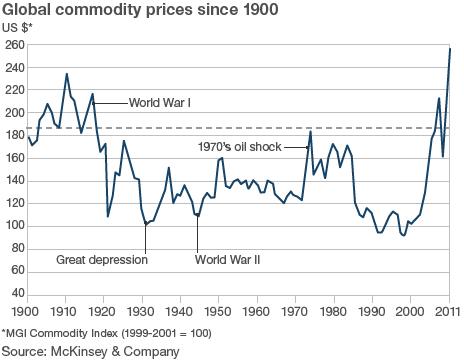

In the past 10 years, global commodity price increases have wiped out all the declines seen during the past century, during which prices almost halved despite a fourfold increase in the world's population and a massive expansion in the global economy.

The reasons for such price falls were simple - the discovery of new sources of relatively cheap supply allied with new technologies.

But the era of abundant cheap resources is drawing to an end, for reasons equally straightforward.

The global population currently stands at seven billion people, and is predicted to rise to more than nine billion by 2050 - that's roughly the population of the UK being added to the planet every year.

More importantly, there could be up to three billion new middle-class consumers, mainly in China and India, according to McKinsey. They will drive demand for meat, consumer goods and urban infrastructure, not to mention the energy needed to produce them, to levels unheard of in human history. For example, McKinsey expects the number of cars in the world to double by 2030.

And while demand for resources from an exploding and wealthier population soars, finding and extracting new sources of supply is becoming increasingly difficult and expensive.

For example, oil companies have to look further and drill deeper to find dwindling reserves of oil, meaning the cost of an average well has doubled in the past ten years, while new mining discoveries have been largely flat despite a fourfold increase in exploration costs.

The discovery of shale gas could have a major impact on meeting global energy needs in the decades to come, but as Laszlo Varro, head of gas, coal and power markets at the International Energy Agency, says, just burning current reserves of fossil fuels using existing technologies would create enough carbon dioxide "to boil the planet several times over".

Water shortages

But it's not just traditional energy sources that are a cause for concern, particularly given that resources are becoming increasingly linked, with shortages and price movements in one having a much greater impact on others.

Take water, which underpins the production of pretty much every manufactured product on earth - for example, almost 50 gallons are used to extract one gallon of oil, says Dr Richard Mattison, chief executive of corporate environmental research group Trucost.

Demand for water over the next 30 years is projected to rise by almost a half at a time when the groundwater table in many regions of the world is falling and large areas are suffering from shortages due to drought, large-scale irrigation, pollution, dams and even war.

Finite land resources are also coming under enormous pressure.

Urbanisation displaces millions of hectares of high-quality agricultural land each year - McKinsey estimates that prime land equivalent in size to Italy could be sacrificed to expanding cities in less than 20 years.

At the same time, tens of thousands of square kilometres of pristine forest are cut down to grow crops needed for food, of which we will need 70% more by 2050 to feed the world's massively expanding population, according to the United Nations.

In fact, vast swathes of natural land are being converted for all manner of uses across the world, destroying essential so-called ecosystem services such as flood protection and genetic resources used for live-saving drugs.

'Critical list'

But it's not just physical depletion that leads to scarcity. For some resources, political and financial factors can exacerbate the problem, particularly in the short term.

A recent survey by consultants PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) found a shortage of key minerals and metals could "disrupt entire economies".

It compiled a "critical list" including lithium, which is widely used in batteries and wind turbines, cobalt, again a key component in rechargeable batteries, and tantalum, which is used in mobile phones and computers.

Geologists prefer not to speculate on the planet's finite reserves of these valuable resources, some of which are already running low, for the simple fact that more could be discovered, but political factors alone make them hard to come by.

China, for example, where most so-called rare-earth elements are found, already severely restricts exports to other countries. India and Vietnam have also curbed exports of mineral resources and the pressure for other countries to follow suit is growing.

Equally, increasingly volatile commodity prices, borne in part of increasing uncertainty over supply, mean companies are less willing to invest in discovering new supplies, unsure of the return they will make on their investment.

This creates a potential vicious circle, where volatile prices have an impact on supply, making prices yet more volatile, all the while exacerbating the problem of scarcity.

Radical solutions

Clearly, then, something has to give if humans are to live within the Earth's means, as they must.

Companies are being forced to spend huge amounts of money to secure their water supplies

As Martin Chilcott, founder of the sustainable business community 2degrees, which counts many of the world's largest corporations among its members, says: "The potentially infinite increase in demand for products is clearly unsustainable.

"Given finite resources, population growth allied with the growing middle classes means the maths just doesn't add up."

Some argue the answers are already out there. Productivity improvements, Mr Thompson says, would alone help meet almost 30% of demand for resources by 2030 and present trillions of dollars of savings to global companies.

New technologies, substitute materials and greater investment in supply will also be needed, he says. McKinsey estimates that about $3tn a year would help meet demand for steel, water, agricultural products and energy. This is about 50% more than current investment.

Others argue more radical solutions are required.

"Policy intervention is needed to protect resources that are not priced or incorrectly priced," says Malcolm Preston, global sustainability leader at PwC.

Water is a case in point. Despite being the world's most precious and increasingly scarce resource, it is incredibly cheap, and in many parts of the world, free.

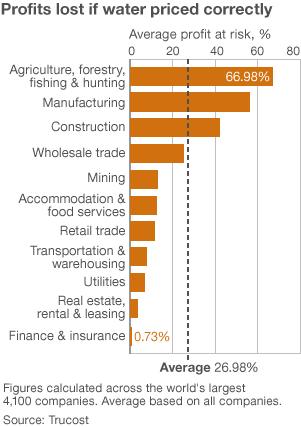

Correcting this price anomaly would have huge consequences for businesses. Trucost has calculated that more than a quarter of profits of the world's biggest companies would be wiped out if water was priced to reflect its value, as it must be.

Land is another example. Huge chunks of the natural world have no monetary value placed upon them, and yet they provide services worth trillions of dollars to the global economy. Only now is this value being recognised and painstakingly calculated.

Energy efficiencies, renewable energy and a massive increase in recycling will also be needed.

Some are even calling for what is known as a circular economy, a comprehensive rethink of our current model of production and consumption, where one company's waste is another's raw material, and where obsession with the ownership of material goods is moderated.

Inevitable for some, an unrealistic step too far for others. But one thing is certain, as things stand the numbers don't add up and the odds are stacked against us. Drastic change is needed.

- Published12 October 2010

- Published27 January 2012