Nature's sting: The real cost of damaging Planet Earth

- Published

The global cost of replacing insect pollination is around $190bn every year

You don't have to be an environmentalist to care about protecting the Earth's wildlife.

Just ask a Chinese fruit farmer who now has to pay people to pollinate apple trees because there are no longer enough bees to do the job for free.

And it's not just the number of bees that is dwindling rapidly - as a direct result of human activity, species are becoming extinct at a rate 1,000 times greater than the natural average.

The Earth's natural environment is also suffering.

In the past few decades alone, 20% of the oceans' coral reefs have been destroyed, with a further 20% badly degraded or under serious threat of collapse, while tropical forests equivalent in size to the UK are cut down every two years.

These statistics, and the many more just like them, impact on everyone, for the very simple reason that we will all end up footing the bill.

Costing nature

For the first time in history, we can now begin to quantify just how expensive degradation of nature really is.

A recent, two-year study for the United Nations Environment Programme, entitled The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (Teeb), put the damage done to the natural world by human activity in 2008 at between $2tn (£1.3tn) and $4.5tn.

At the lower estimate, that is roughly equivalent to the entire annual economic output of the UK or Italy.

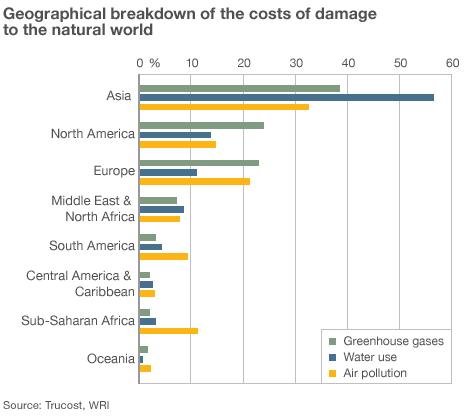

A second study, for the UN-backed Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), puts the cost considerably higher. Taking what research lead Dr Richard Mattison calls a more "hard-nosed, economic approach", corporate environmental research group Trucost estimates the figure at $6.6tn, or 11% of global economic output.

This, says Trucost, compares with a $5.4tn fall in the value of pension funds in developed countries caused by the global financial crisis in 2007 and 2008.

Of course these figures are just estimates - there is no exact science to measuring humans' impact on the natural world - but they show that the risks to the global economy of large-scale environmental destruction are huge.

Natural services

The reason the world is waking up to the real cost of the degradation of the Earth's wildlife and resources - commonly referred to as biodiversity loss - is because, until now, no one has had to pay for it.

Businesses and individuals have largely operated on the basis that the natural resources and services that the planet provides are infinite.

But of course they are not. And only when the value of protecting them, and in some cases replacing them, is calculated, does their vital role in the global economy become clear.

Some are obvious, for example the clean and accessible water that is needed to grow crops to eat, and the fish that provide one-sixth of the protein consumed by the human population.

But others are less so, for example the mangrove swamps and coral reefs that provide natural barriers against storms that devastate coastal regions; the vast array of plant species that provide pharmaceutical companies with endless genetic resources used for live-saving drugs; and the insects that provide essential pollination for growing around 70% of the world's most productive crops.

Bee collapse

It is a hugely complex process, but an economic value can be placed on these resources and services.

In the US in 2007, for example, the cost to farmers of a collapse in the number of bees was $15bn, according to the US Department of Agriculture, contributing to a global cost of pollination services of $190bn, according to Teeb.

Deforestation increases the risk of flooding in surrounding areas

As Paven Sukhdev, a career banker and team leader of Teeb, says: "Bees don't send invoices".

Research by consultancy group PricewaterhouseCoopers also suggests the economic losses caused by the introduction of non-indigenous, agricultural pests in Australia, Brazil, India, South Africa, the US and the UK are more than $100bn a year.

In 1998, flash flooding in the Yangtze River in China killed more than 4,000 people, displaced millions more and caused damage estimated at $30bn. The Chinese government established that extensive logging in the region over the previous 50 years had removed the trees that provided essential protection from floods. It promptly banned logging.

Indeed the Centre for International Forestry Research has estimated that, in the 50 years prior to the ban, deforestation cost the Chinese economy around $12bn a year.

Business costs

The impact of biodiversity loss is felt hardest by the world's poor. The livelihood and employment of hundreds of millions of people depend upon the world's natural resources, whether it be fish to eat or sell, fertile soil for farming or trees for fuel, construction and flood control, to name just three.

As Mr Sukhdev explains: "Biodiversity is valuable for everyone, but it is an absolute necessity for the poor".

For example, Teeb has calculated that the Earth's natural resources and the services they provide contribute 75% of the total economic output of Indonesia, and almost half of India's output.

But it's not only the poor who suffer.

Businesses will increasingly be hit as they start paying for their part in biodiversity loss.

Not only will they have to pay to protect or replace services that nature has historically provided for free, but they will be forced to pay by regulatory instruments such as pollution taxes, like carbon credits and landfill taxes that already exist, and higher insurance premiums.

Increased flooding is partly due to land conversion by humans

Then there is the cost of paying for the increased number of natural disasters, resulting in part from more extreme weather conditions caused by rising temperatures due to greenhouse gases, and even reputational damage among consumers that are becoming increasingly sensitive to environmental issues.

Trucost and PRI have estimated the cost of environmental damage caused by the world's largest 3,000 companies in 2008 at $2.15tn.

That equates to around one-third of their combined profits.

Again, these figures are only estimates, but the scale of the costs that will have to be paid by companies for their damage to the environment cannot be ignored.

As Gavin Neath, senior vice president of sustainability at consumer goods giant Unilever, says: "It's pretty terrifying. Nobody in business thinks that at some point this is not going to hurt us".

Pension values

And higher costs for business mean higher prices for consumers.

Only this summer, massive floods in Pakistan and China forced the global cotton price to 15-year highs, pushing up the costs of clothes, with retailers such as Primark, Next and H&M all warning of higher prices to come.

Drought and wildfires in Russia also sent wheat prices rocketing, sending global food prices sharply higher.

But consumers won't just be hit by rising prices. As Trucost's research shows, earnings and profits of the world's largest companies will come under increasing pressure, undermining share price growth.

And it is precisely these companies that pension funds invest in.

Pension values, therefore, are likely to suffer, reducing retirement incomes for all.

The cost of the current, rapid rate of degradation of the earth's natural resources will, then, be borne by everyone, environmentalist or not.

This is the first in a series of three articles on the economic cost of human activity on the natural world.

The second looks at which sectors and businesses have been hit hardest, and the third looks at what can be done to slow biodiversity loss, and what opportunities it presents.

- Published7 October 2010

- Published24 September 2010

- Published3 September 2010