Brics catch high-frequency trading habit

- Published

Fast and furious automated trading is spreading across the globe

Ultra-fast trading has transformed global markets in recent years, but regulators have been accused of an ultra-slow response to changing times.

Thanks to complex computer software and algorithmic formulae, it is now possible for stocks, shares, currencies and commodities to change hands in fractions of a second, without the need for human intervention.

In the financial centres of Europe and the US, where the practice began, the people responsible for policing the markets are getting worried about their ability to cope.

But while they talk about how to curb it, trading based on algorithms is not going away. In fact, it is spreading faster than ever, as emerging markets catch on to its potential.

"The Bric (Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries are where it's at right now," says Dr John Bates, executive vice-president and chief technology officer of Progress Software, a company that has pioneered new techniques in what are known as quantitative trading programs.

"We've seen it grow very quickly in Brazil. It's done what happened in London and New York much more quickly. Now we're seeing the same trend in India and China and even, embryonically, in Russia."

According to Dr Bates, in the past two to three years, Brazil has already run through a cycle of development that took far longer in London and New York, with algorithm-based trading now available in equities, futures and foreign exchange markets.

Brazil's Bovespa stock exchange has invested in new technology, boosting the proportion of algorithm-based equity trades from 4% to 12% in the past year.

"The adaptation is faster and they can leapfrog the mistakes that have been made in other places," he says.

Backlash looms

Dr Bates says India is already following suit and will see even more automated trade in the next few years: "The market's gone very electronic there." But India is also seeing the first stirrings of disquiet at the spread of high-frequency trading.

Ian Ellis, director at Ride Arcade Limited, explains how electronic trading works

The chairman of the Securities and Exchange Board of India, UK Sinha, has said he is considering whether a speed limit should be imposed on ultra-fast automated trading of Indian stocks.

"As there is a rush towards reducing transaction time in the name of high-frequency trading, the question we need to ask is what purpose are we serving by reducing trading time to eight microseconds or even two microseconds. Is this justified?" he told the Asian Financial Forum in Hong Kong in January.

Indian analysts reckon that as many as a quarter of all trades in the country now involve algorithms, still mainly in equities, whereas up to half of all transactions in Europe and nearly two-thirds of US transactions are estimated to come from high-frequency and algorithmic trading.

In Europe, there is pressure for the EU to curb the spread of ultra-fast trading as part of a much-anticipated regulatory reform due out later this year.

The head of France's AMF watchdog, Jean-Pierre Jouyet, has called for the revised Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (Mifid) to allow supervisors to police high-frequency and algorithmic trading more effectively.

"Limiting the spread of these trading techniques, the benefits of which are dubious, will make our markets more stable and clearer for investors without jeopardising genuine liquidity," he told the European Parliament in December.

In the US, meanwhile, regulators such as the Commodity Futures Trading Commission are struggling to define what high-frequency trading actually is. As one member of the commission put it: "We want to understand what we're regulating."

Traffic police

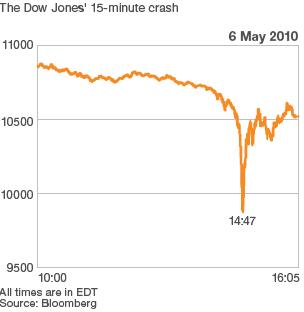

The dangers of high-frequency trading are illustrated by the so-called Flash Crash of May 2010, when the US stock market plummeted 700 points in just a few minutes, wiping out about $800bn (£517bn).

In Mr Jouyet's view, this was caused by what he calls "trend-following volume". In other words, a whole host of different automated traders, using the same algorithms, carried out similar trades at the same time, reinforcing the market downturn and magnifying its impact.

Progress Software's Dr Bates recognises the dangers, but compares them to the risks involved in driving a fast car.

"If I were to get into a Ferrari and drive off like a lunatic, I could cause damage to myself and others," he says. "But hopefully, there would be some traffic police out watching and they would be able to pull me over before I got into trouble."

For him, that means having regulatory supervision that uses the same techniques as high-frequency traders, in order to spot when they are going wrong. And in fact, Progress Software has been working with the UK's Financial Services Authority and many leading banks to do just that.

"We've been involved on both sides of that story," he says. "It's very possible to spot a trade that's gone out of control. It's very possible to spot an algorithm that's gone out of control and shut it down before it does harm.

"There are some bad apples out there, but not that many, and we need to have systems that can catch them in the act."

'Race to zero'

Of course, having a fancy algorithm is only half the story where ultra-fast trading is concerned.

As well as the right software, you need hardware that can deliver the speed you need - or, in the jargon of the industry, you need a digital network with ultra-low latency.

"If you have the fastest network, you're the sexiest girl in the class, you're the top boy," says Fraser Bell, managing director of BSO Network Solutions. "It's as simple as that."

BSO operates its own international network covering the UK, the US and 16 other countries, including the main European financial markets, Hong Kong, Singapore, Brazil and Russia.

It prides itself on being able to send data from London to Hong Kong and back in just 174 milliseconds.

"There's a massive global drive for speed," says Mr Bell, who sees himself as locked in a "race to zero" with rival network operators.

Meet the modern co-ordinator of algorithms

The fiercely competitive nature of his business is clear. BSO's website urges financial firms to sign up with it "because a millisecond can cost millions".

And whereas a company in any other line of business might sign a three-year or five-year contract with an IT services provider, BSO's service-level agreements might be for as little as one year. Like a mobile phone contract? "Exactly," says Mr Bell.

But if trades are being placed by robots and then being supervised by robots, where is the human element in all this? Well, Progress Software's Dr Bates says it is still "critically important".

"The traders used to be the boys and girls in the pits wearing special jackets, then they moved to sitting behind a terminal.

"But now the trader is a high-level co-ordinator of algorithms, the validator of the algorithmic suggestions. It's not Skynet taking over the world," he says, referring to the villainous computer system in the Terminator films.

Clearly the network builders and the mathematicians are thinking quite differently from the regulators about ultra-fast trading. The race to zero could end up facing speed bumps in the future.

- Published26 September 2011

- Published23 August 2011

- Published1 October 2010

- Published18 August 2011