Wonga: What makes money lender tick?

- Published

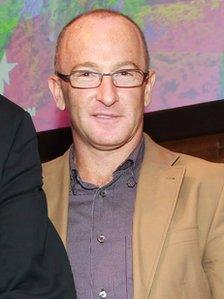

Errol Damelin launched Wonga in 2007

In just a few years, Wonga has become one of the country's biggest, and certainly fastest growing, money lenders.

Since it started in the autumn of 2007 it has made four million small, short-term loans, amounting to more than a billion pounds in all.

The firm has attracted plenty of criticism, suggesting it is little better than a digital loan-shark, exploiting the skint and vulnerable.

In January the firm was at the centre of controversy about adverts encouraging students with jobs to take out loans to pay for things like trips abroad.

And in March fans of some football clubs called for the company's adverts to be removed from their clubs' websites.

This week it attracted more attention by launching a loan service aimed at businesses which are short of cash.

Errol Damelin, Wonga's founder, is remarkably unperturbed by the critics.

At a briefing for journalists this week, he was happy and confident about the prospects for his business, and also the legitimacy of short-term money lending.

According to him, Wonga is the equivalent of iTunes for the financial world.

"Wonga is a platform for the future of financial services, the digital revolution has not yet begun in financial services," he said.

Likening his company to firms like Google, Amazon, PayPal and Netflix, he argued that using technology and data about his customers would be the key to success.

"Wonga is on a multi-year and multi-decade journey to build the future of financial services, using data and technology to make objective and unprejudiced decisions," said Mr Damelin.

How it works

People borrow money from Wonga by applying on its website.

This offers a swift decision and then transfers the money into a bank account within 15 minutes.

The firm employs more than 100 staff just to develop its technology and make sure the site works properly.

Its key feature is that it combines information about potential customers in a massive in-house credit scoring operation.

Errol Damelin said his computers use artificial-intelligence software to collect and digest up to 8,000 different pieces of information about applicants to decide if they should be offered loans.

"We have built the world's first, completely straight-through processing system for credit, so when somebody comes to Wonga as an individual, or as a business-owner, and applies for a cash advance, the whole process is completely automated," he said.

So, no more putting on a suit and tie and begging a bank manager for a loan or a bigger overdraft, at least for short-term cashflow problems.

Selectivity

Wonga's technology filters out applicants who are thought to be too risky, and about 66% of them are currently turned down for not being credit-worthy.

In England, Wonga sponsors Blackpool football club

For instance you have to have a regular income, a bank account, a functioning debit card, a mobile phone and a good credit record.

The result of this filtering is that so far only about 7% of Wonga borrowers have failed to repay.

This is a lower level of default than the 10% bad debt rate on credit card lending, which has led banks to write off billions of pounds in the past few years.

The credit scoring process, however, is more sophisticated than just asking a few simple questions.

The firm's technology allows it to measure how the customers use the website itself, as this offers some valuable insights.

For instance, potential borrowers use the online sliders on the computer screen to determine how much they want to borrow and for how long.

The firm has found that people who immediately shove the slider up to the maximum amount on offer, currently £400 for 30 days for a first-time applicant for a personal loan, are more likely than others to default.

"The great thing about that is that our decisions are always objective, we are not subject to the same kind of imperfections that traditional lenders have, where different bank managers have different preferences and often prejudices which affect how people get access to credit," Damelin argued.

High interest

What about the cost?

Wonga makes no bones about the fact that the APR it charges, a standard measure of interest costs, is a frankly incredible 4,214% a year.

That is stated clearly on the front page.

Borrowers are told exactly how much they will have to repay, and when.

But Errol Damelin said that for his target audience, price is not the issue, and nor should it be.

Speed, convenience and transparency are what he is selling - as well as cash.

"We have dared to ask some hard questions, like how can we make loans instant, how can we get money to people 24 hours a day, seven days a week, how can we be totally transparent?" he said.

"So what we have built is a solution around speed and convenience, and helping people by dealing with them when they want to deal with us."

Fresh scrutiny

Wonga rejects the criticisms of its business by pointing out that its users appear very happy.

Using a measure of customer satisfaction called the "net-promoter" score, it says it has a score of more than 90%.

In essence, most of its customers would be happy to recommend its services to their friends and family.

By contrast, most banks have negative scores, and even highly-rated banks like First Direct score less than 50%.

Even so, the regulated money lending industry has a poor image and is coming under renewed scrutiny.

The Office of Fair Trading (OFT) announced in February that it would look again at the lending practices of the many firms that offer payday loans.

Two years ago it concluded that they and other high-cost credit businesses - like home-credit lenders and pawn brokers - should not have their interest rates capped.

Now it is concerned again at shoddy selling practices, like targeting loans at people who cannot afford them, and letting their debts roll over to become bigger.

Wonga insists it has nothing to do with the spivvier end of the growing payday lending business.

For Errol Damelin, the target now is to widen his business by lending to small companies suddenly short of cash.

"Financial services is a challenging place to innovate in, so we are responding where we can deliver a better service," he says.

"Businesses have been crying out for a solution that is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to solve relatively small, relatively short-term cashflow problems."

- Published14 January 2012

- Published11 January 2012

- Published11 January 2012

- Published13 December 2011

- Published15 June 2010