Africa's middle class: Fact or fiction?

- Published

Diageo will be producing a million of bottles of Meta a day by 2013

Africa's billion-plus population is increasingly being investigated by foreign and local companies alike for signs of a burgeoning middle class.

Potentially, it represents one of the biggest markets in the world - people with a disposable income which companies can turn into profit.

As part of its focus on emerging markets, the drinks giant Diageo has bought one of Ethiopia's previously state-owned breweries.

Order a drink in one of the increasingly numerous bars in Addis Ababa, the country's capital, and alongside Diageo's premium brands such as Johnny Walker and Smirnoff sits the more humble locally brewed Meta beer.

"Our strategy is to invest in the Meta brand," says the country's Diageo managing director, Francis Aghom Agbonlahor.

"It is an iconic brand. We want to see it reflecting its past glory and we want to double the size of the newly acquired brewery within the next three years."

Brand awareness

Mr Agbonlahor is happy with the government's privatisation process but there are still hurdles when running a business in a country like Ethiopia.

"Bureaucracy is a bit of a challenge," he says, "Sometimes you have to go at it two, three or five times before you can get something approved. You need a little patience."

Around Addis Ababa there are are huge billboards displaying Diageo products.

"Advertising was near dormant before we came here. When we put up our first 15 billboards, we were the only ones across the capital," he says.

Within a few weeks, every other competitor had placed similar hoardings around the city.

"Competition is good for the market and good for the consumers. The consumers have been neglected and now everyone is copying what we started," he says.

He believes this will lead to increased consumption as the economy begins to grow, and then it depends on choices and what people can afford.

"The key thing is to be able to provide what the consumers are looking for."

Social mobility

But is an increase in the company's African business a sign of a middle class emerging?

"I'm not sure what middle class is in the context of Africa," muses Nick Blazquez, head of Diageo Africa.

"They aspire to improve their lot; to provide education for their children; to progress themselves. In that regard they aspire to brands in the same way as consumers around the world aspire to brands," he says.

"We are seeing consumers coming out of the illicit and informal sector - leaving illicit and sometimes unhealthy alcohol and into the consumer branded goods sector, so we see trading up from illicit to formal sector, and within the formal sector people are trading up to more premium brands."

"Within the alcohol beverage sector, consumption correlates most closely with GDP (gross domestic product) growth, so the more money people have, the more they spend it on brands and on premium brands," he asserts.

'Realities'

Not everyone equates the rise in GDP as proof of there being a middle class.

According to Duncan Clarke of the management advisory group Global Pacific, 70% of Africans live on or below the $2-a-day range, and in some countries the figure is higher.

"You have a mix in Africa of medieval and modern economies in which there is not an overwhelming middle class, so it is important to have an accurate perspective and look at the prism of this through the realities of the historic evolution of the economies," he says.

"While markets and consumers will grow, it is nothing like the image of middle class bliss as projected by the media and the corporate cheerleaders."

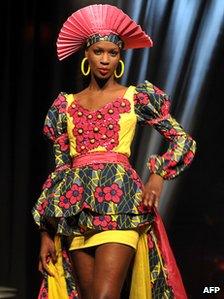

High fashion is a luxury very few can afford in Africa

So are the likes of the retailer Walmart and Diageo making a mistake by investing?

"They can judge for themselves. They can spot opportunities," he says.

"I am just trying to put a perspective into context about the real scale of the middle class in Africa.

"The actual real middle class in Africa that sits in a global middle-class income level is less than 5% - that would be about 50 million people spread in different countries across the continent, concentrated largely in some high-income countries such as South Africa and Nigeria."

Mr Clarke maintains that even in Ethiopia and Kenya, where there are some rich people, the impression that there is this vast middle class does not stack up to the world's values and standards.

"There are people with more money and they are benefiting from the growth over the past couple of years," he says.

But with economic growth comes the downside, and everyone complains how prices are rising every time they go into a shop, and how they have to constantly make decisions about whether to buy food or clothes, or put petrol into their cars.

"How governments handle this inflation will determine how the economy will play out and whether this upbeat mood about the economy will continue," adds Mr Clarke.

- Published5 May 2012

- Published29 March 2012

- Published18 January 2012