Global powerbrokers focus on food and water scarcity

- Published

Droughts, such as this one in South Korea, put pressure on water supplies

The man from the United Nations is not sugar-coating the threat he says the world faces as a result of future food, water and energy shortages.

"We know clearly that inequalities around food, water and energy wealth do create wars," says David Nabarro, UN special representative on food security and nutrition.

"They may not always be the direct trigger... but unless they can be dealt with, the future for all of us is going to be very difficult."

Mr Nabarro is speaking at a conference of the world's great and the good in Oxford.

Held in the rarefied environment of Oxford University's Examination Schools building, you know you are at a high-profile event when former US President Bill Clinton walks past surrounded by his security agents.

The UN's David Nabarro says governments need help from businesses to tackle resource scarcity

Rwandan President Paul Kagame is also here with his protection team, as are Nobel prize-winning economists, and bosses of some of the world's largest food companies, including Nestle and Coca-Cola.

The Resource 2012 forum has also attracted investment fund chiefs from around the world who, according to the event's organisers at Oxford University, control a combined $5 trillion (£3.2tn).

Sir David King, director of Oxford University's Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, and co-director of the event, used his opening address to tell the 250 delegates that Resource 2012 was definitely aiming to be "Davos-style".

This is in reference to the meeting of the World Economic Forum held every January in the Swiss ski resort of that name, which attracts the same demographic of world leaders.

Financial incentives

Resource 2012 starts with the commonly agreed estimate that the world's population will increase from the current seven billion people to nine billion by 2050, and that this will put significant pressure on food, water and energy supplies.

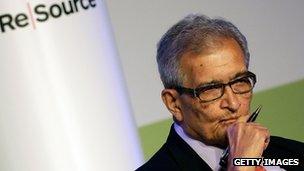

Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen favours financial incentives to get firms to invest in renewable energy

With a number of discussions being held over two days, it aims to explore the best ways to tackle future resource scarcity.

In a discussion about future energy supplies, Nobel prize-winning economist Prof Amartya Sen says governments still had to do more to encourage companies to invest in renewable energy.

"I think the main thing to look at is how the financial incentives can be changed to the direction we would like them to be changed," he says.

"The way to make the financial sector [move more towards renewables] is not moral exhortation, but to increase the financial incentives."

For Mr Nabarro, he says that while governments were focusing more on the problem of resource scarcity, they still need businesses to help them tackle the issue because of the short-termism inherent in modern democracy - politicians chasing votes every five years or so.

He explains: "We are beginning to see political organisations putting equity and access to food at the centre of political discourse, alongside terrorism and the global financial markets.

"But politicians cannot do it on their own - their electorates won't let them."

'Resource optimisation'

Paul Kagame leads one of Africa's smallest countries. Landlocked Rwanda also has the continent's second highest population density.

The Rwandan president tells Resource 2012 that countries have to work together to develop the specialisms to make agriculture more productive.

"It is clear that rising global demand and competition for the key but finite resources of water, energy and food cannot be ignored," he says.

"It is estimated that by 2030 the world will need 40% more fresh water, and 50% more food and energy. This increase is partly due to expanding population, and increased urbanisation and prosperity.

"In light of this, the world has to figure out how to optimise such vital resources, and also to search for new ones."

Biofuel problem

Among the food company bosses present, Nestle chairman Peter Brabeck-Letmathe is highly critical of the rise in the production of bio-diesel, citing the pressure this puts on food supplies by using up land and water that would otherwise have been used to grow crops for consumption.

"I'm not pessimistic, I am just saying that we will have to adapt," he tells the BBC before addressing his fellow delegates.

"The time of cheap food prices is over. We are now in a new world with a completely different level of food prices, and with high volatility, because of the direct link with fuel."

Mr Brabeck-Letmathe says this was an issue for governments to resolve, saying they should cut biofuel subsidies.

"Biofuels are only feasible because of the high subsidies they receive - $25bn so far. If you used this money to feed people, then perhaps you would have less than one million people going hungry."

As the discussions continue, it is apparent that none of the delegates are complacent about the scale of the problem of future resource scarcity. Agreement on the solutions, however, could be harder to come by.

- Published19 June 2012

- Published12 June 2012