Serious Fraud Office: A chequered history

- Published

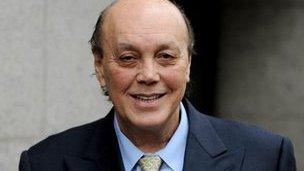

Asil Nadir was found guilty of theft following a lengthy SFO investigation

The Asil Nadir case is the longest and one of the most high profile that the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) has undertaken.

It was uniquely difficult. After almost two decades, a third of the original 300 witnesses could not be traced. Several had died.

About 1,400 boxes of evidence had to be prepared for the new trial.

Some documents had suffered a microbial infection and had to be subjected to heat treatment.

So the conviction of Nadir will be seen as a vindication of the SFO, which has had a chequered history and which recently faced the prospect of being broken up.

The director of the SFO, David Green, said: "The conviction of Asil Nadir of theft on a grand scale from a public company 19 years after he fled the jurisdiction is a remarkable achievement."

'Notable failures'

The SFO is an independent government department that investigates and prosecutes allegations of complex fraud and corruption.

It was born out of the Roskill Report which was itself a response to a series of financial scandals that had hit the reputation of the City of London in the '70s and '80s.

The report called for a new unified organisation responsible for detecting, investigating and prosecuting serious cases of fraud.

The SFO was created as part of the Criminal Justice Act of 1987 and began operating a year later.

Over the years it has tackled some of the biggest fraud cases in UK history.

'Seriously Flawed Office'

But it has had mixed fortunes, says Stephen Parkinson of law firm Kingsley Napley.

"In the past it hasn't brought the big flagship cases home - the ones upon which the reputation of the office depends," he says. "There have been some notable failures."

In the '80s and '90s, the SFO brought a series of prosecutions involving some of the most well-known companies and individuals of the time.

The names - Guinness, Blue Arrow, Barlow Clowes, Brent Walker, the Maxwell brothers - have gone down in legal history.

But time and again defendants were acquitted and cases collapsed. Often it only won partial victories.

By the time Ros Wright took over as director of the SFO in 1997, a press backlash had already begun.

"Sadly it had already achieved the reputation of being called the Seriously Flawed Office," she says.

"Suddenly the scales fell from the public's eyes, they realised that they actually might lose cases too. And then all hell broke loose in the media and they, I think, started gunning for the SFO in a big way."

The trail involving Ian and Kevin Maxwell is said to have cost £25m

In the 1990s, the SFO brought four trials linked to allegations of share ramping during the takeover of the Distillers Group by Guinness. Two of the trials collapsed. While four businessmen were convicted, four others were eventually acquitted.

The 1992 Blue Arrow case, which is thought to have cost £40m, was one of the longest in English criminal history.

It was again linked to allegations of share rigging during a takeover. But of 14 defendants, just four were convicted by a jury. All were subsequently cleared on appeal.

The 1994 Brent Walker trial also cost around £40m.

But George Walker, who was accused of inflating profits at one part of the firm, was cleared of all charges.

Ian and Kevin Maxwell, the sons of the disgraced publishing mogul Robert, were cleared of charges of being involved in a conspiracy to defraud the company's pensioners after an eight-month trial that cost some £25m.

More recently, its handling of investigations into alleged bribery by BAE Systems was criticised. Campaigners accused it of ending a probe into the firm's aircraft deals with Saudi Arabia in the face of intense pressure from government. The SFO denies coming under pressure.

And there have been successes, too.

In 1992, Peter Clowes was sentenced to 10 years in prison when he was found guilty of a £17m investment fraud.

The SFO says that in recent years around 80% to 90% of defendants brought to trial have been found guilty.

Break-up threat

But that hasn't stopped calls for changes.

Last year, Home Secretary Theresa May proposed breaking up the SFO. The plan involved putting its lawyers into the Crown Prosecution Service and its investigators into the new National Crime Agency that will be set up next year.

But she failed to win the support of cabinet colleagues for the changes.

There was also disquiet over a change of tack which saw more cases being settled before they went to court.

"More recently, the criticism has been that it hasn't simply been prosecuting enough cases," says lawyer Stephen Parkinson.

In May, the SFO rebutted claims from a law firm that the agency had not conducted a single raid over a 12-month period.

Then last month the High Court ruled that search warrants issued to the SFO as part of its investigation into the property tycoons the Tchenguiz brothers, were unlawful and obtained by "misrepresentation".

Needed?

Supporters argue that the SFO is needed more than ever.

It recently launched a criminal investigation, in the wake of the Libor scandal, into the rigging of inter-bank lending rates.

Fraud is also growing. The National Fraud Authority claims there is £73bn worth of fraud in the UK every year, the equivalent of £1,030 for every man, woman and child in the country.

"We are losing, haemorrhaging money if you like, through white-collar crime," says Ros Wright, who now chairs the Fraud Advisory Panel. "It's an area that's got to be tackled and has got to be tackled very effectively."

But according to the SFO's Annual Accounts, its budget will fall from £52.8m in 2008-9 to £31.0m in 2014-15.

And critics warn that one consequence is that experienced lawyers have been replaced by administrators.

"Over the past few years a lot of the expertise that was there has been drained away," says Ms Wright. "They need to recruit some more expertise as quickly as possible but they don't at the moment have sufficient funds to do that."

Stephen Parkinson agrees. "It's meant to have a workload of about 100 cases of the utmost seriousness," he says. "It's wholly impossible to investigate and prosecute that amount of cases with that amount of money."

SFO director David Green said the result of the Asil Nadir case confirmed that "the proper role of the SFO is to investigate and, where appropriate, to prosecute the most difficult cases of fraud and corruption".

He added: "These cases are high profile and carry high risk; they can only be addressed with clarity, expertise and resilience."

- Published22 August 2012

- Published22 August 2012

- Published22 August 2012

- Published20 August 2012

- Published31 July 2012