How do you stop online students cheating?

- Published

Online universities are growing, but how will home students verify their identity?

Imagine taking a university exam in your own home, under the watchful eye of a webcam or with software profiling your keystrokes or your syntax to see whether it really is you answering the questions.

Online university courses have become the Next Big Thing for higher education, particularly in the United States, where millions of students have signed up for courses from some of the most upmarket universities.

With spiralling costs and student loan debts crossing the trillion dollar barrier this year, the online university has been seen as a way of reaching many more people for much less money.

But a major stumbling block has been how such digital courses are assessed.

When students are at home how do you know whether they are cheating? How do you know the identity of the person answering the questions?

For the online courses to gain value, they need a credible way of assessing students and an important part of that is preventing fraud.

Home exams

The Open University in the UK has been a pioneer of distance learning.

"It's a common problem across the sector - how do you know that the individual taking the exam is the right person?" says Peter Taylor, chair of the Open University's academic conduct group.

An important attraction of online courses is that students can study where and when they want - and he says the university is looking at ways of letting people take exams at home.

Anant Agarwal, head of edX, is offering real exam centres for online students

"We're looking at whether we can do online examinations, so the student doesn't have to come in to a hall, they just need to be sitting in front of their computer at a particular time when the exam is released to their computer," says Prof Taylor.

"Their computer would be locked down so that it can't use other materials. If you've got an appropriate webcam - that can provide you with effective invigilation."

"I've not yet seen systems which I'm confident about at the moment - but I don't think it will be too long before these problems are resolved."

Online identity

This still raises the question about how you know who is sitting the exam.

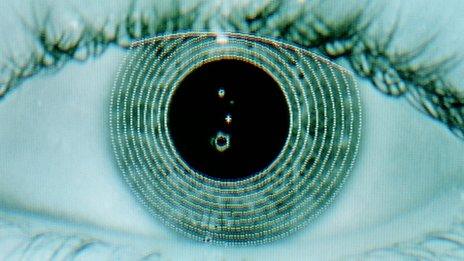

"There are various ways you can identify a person," says Prof Taylor.

"One system we looked at meant that you had to type in a particular phrase - and the rate and the particular way you type is effectively a signature of the individual."

These are not distant-horizon ideas - Prof Taylor says he would expect such technology to be in place within the next five years.

He also says that there is no reason to think more people would necessarily cheat online.

"Let's face it, in a large examination hall, each individual student isn't going to be closely watched. The idea of people bringing notes up their sleeves remains a problem."

EdX, an online university project set up earlier this year by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, wants to make more use of the exam hall rather than less.

Students taking edX online courses will be able to sit their final exams in an international network of test centres, run by Pearson Vue.

These will be formally supervised on-screen exams, using the edX website, and those who pass will receive a "proctored certificate", showing it has been achieved in an invigilated setting.

Bricks and mortar boards

"This is a very important step," says edX's first president, Anant Agarwal. "Because people have been concerned that learners had no way of showing that they had done the work themselves, if they were applying for a job or for higher education."

With enough randomly generated questions, he says, it would be possible to grade the work of tens of thousands of students at different times around the world.

Harvard is among the new wave of top universities offering courses online

Such online testing techniques are going to have an impact on the traditional university course too, he says.

"Online education is like a rising tide, it's going to lift all boats," says Prof Agarwal.

Students really like the instant feedback of online testing, he says. And interactive, multimedia online lectures make the old-style lectures look less effective.

But this volume of testing depends on automated marking - and will mean a limit on the range of subjects and type of questions that can be examined.

A computer is going to struggle to mark an essay on irony.

Industrial scale marking

That's the challenge for another of the most significant online course providers, Coursera, set up by Stanford academics and backed by Silicon Valley investors.

It has attracted students remarkably quickly - 1.6 million have signed up in the first year, taking courses from more than 30 top universities.

When the University of London's international section joined last month, 9,000 students signed up in the first 24 hours.

But how can such large numbers of candidates be reliably marked?

Coursera's co-founder Daphne Koller says trying to find a way to assess so many students is "part of the learning process".

She says automatic marking can generate a score or a grade, but students want human feedback. And there isn't any technology that can judge whether an essay has really connected with a question.

The Open University's Prof Taylor says their own experiments have shown that any software for assessing free-text answers requires a large amount of human intervention.

"Decisions about the quality of work are made by academics. There has to be a human brain in there somewhere," he says.

Coursera has been experimenting with peer assessment, where students grade each others' work, following guidelines set by the teacher.

This allows for the marking capacity to grow with the class size - but it also depends on the reliability of fellow students.

These online courses are also being discussed online - and blogs from students refer to disagreements over marking.

For instance, there are disputes among this global student body over British or American spellings.

Honour code

This brings the debate back to an old fashioned and low-tech form of preventing cheating.

The "honour code" - or should that be "honor code" - is an ethical approach, based on a promise to maintain academic honesty.

And there is research suggesting it really works and institutions with such a code have a lower level of cheating.

Keystroke measurements and iris recognition could verify a student's identity

The need to establish a reliable system to stop online cheating is fast becoming a mainstream concern.

The latest recruit to edX, the University of Texas, says it wants to charge tuition fees for online courses that will count towards degrees - which will mean the same level of rigour in testing as traditional courses.

Martin Bean, vice chancellor of the Open University, said: "There is no doubt that this is the 'web moment' for higher education and a battle is shaping up for growing student numbers on global courses online, with some able to grow large numbers of students very quickly.

"However this is a battle which will be about brands and the market ability of the providers but also, crucially, about quality of teaching and credibility."

- Published20 June 2012

- Published17 October 2012

- Published19 September 2012