Cable rehabilitates investment banking

- Published

- comments

I have been a bit confused about what the new business bank being set up by the government will do, and I fear that is only in part because I have been away for a bit.

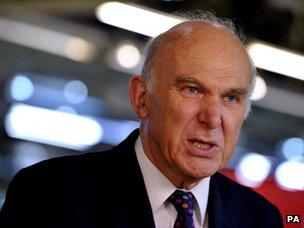

With Vince Cable set to announce today at the LibDems' annual conference that £1bn of public money will go into it, I thought I should try to find out a bit more about its aims and designs. So, for what it's worth, this is what I have learned.

First, this is an attempt at serious structural financial reform to provide longer term, stable loans to smaller businesses, not a quick fix. The bank will take at least 18 months to get going, so will do nothing to tackle the current perceived shortage of loans for smaller businesses (the Bank of England's Funding for Lending is the putative quick fix).

Second, it will not actually provide any loans itself. This will be a new private-sector investment bank (though, presumably for PR reasons, officials prefer to call it a "wholesale bank"), in which the government will have a stake of around a third. And it will buy loans that banks - including the High Street banks - have made to smaller companies.

The intention is that these would be longer-term loans with a maturity of about 10 years, that small businesses find hard to prise out of our risk-averse banks.

The new bank would then package the loans into bonds and sell them to investors, such as pension funds.

In other words, it is the latest initiative to provide the financial bridge that British industry has wanted for more or less as long as I have been conscious of the existence of British industry, viz long-term finance for growing companies from the institutions that invest for the long term.

To put it another way, it is an attempt to give securitisation - the packaging of loans in to bonds, the process that wreaked so much havoc in the 2007/8 financial crisis - a good name.

That is more than a vain hope.

Arguably one of the great weaknesses of the British and European economies is that capital-strapped banks play too dominant a role in the provision of vital finance to businesses (and households). For all that the US recovery is seen in the US as too weak, one of the reasons it has been stronger than Britain's is that Americans can in effect borrow from investors, rather than banks, in a way that does not happen here.

Unlocking the funding potential of British pension schemes and insurance companies may well be a good thing.

How much additional long-term lending could go to Britain's family-owned companies and their ilk? Well if the government's £1bn of equity and guarantees is there to absorb potential losses of - say - 10% on the value of the loans being made, then it could underpin about £10bn of incremental lending.

Which would be a useful addition to an under-developed market.

By the way, the reason the government wants to be only a minority investor in the new bank is that - with the public finances mending at snail's pace - it feels obliged to limit the exposure that appears on its own balance sheet to £1bn, not the multiple which may be provided to companies in the form of finance.

So there is a bit of creative accounting by the Treasury. But small companies won't give a damn, if - like their German and US counterparts - they get access to loans that can't and won't be withdrawn as and when they and the economy catch another cold.