Food price crisis: What crisis?

- Published

Corn crops in the US have been devastated by the worst drought in 50 years

Without water, crops cannot grow and the world cannot eat. And this year, there hasn't been enough of it.

The US has seen its worst drought in more than 50 years, vast swathes of Russia have been left parched by lack of rain, India has had a dry monsoon, while rainfall in South America early in the year fell well below expectations.

As a direct result, harvests of many crops have been decimated, forcing the price of some cereals back up towards levels last seen four years ago, a time when high prices sparked riots in 12 countries across the world and forced the United Nations to call a food price crisis summit.

The lack of rain this year has raised fears we are rapidly heading for another price crunch.

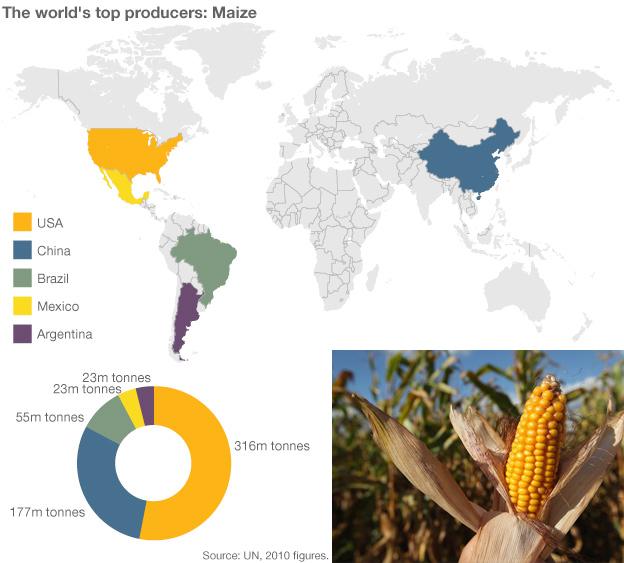

The focus has been on US corn production, which has been all but wiped out in many regions. In fact, US corn inventories are running at just 6% of annual consumption, well below the 25% that is generally considered an appropriate buffer.

Soya-bean production is also well down, while grain production in Asia has been hammered, with yields in some countries down by more than 50%.

.jpg)

And yet most experts agree the situation is nothing like as dire as it was four years ago, nor in fact two years ago when droughts again hit food production hard, sending prices to record highs.

Prices are measured against expectations, and harvests have not been as bad as many had feared. More importantly, stocks are in better shape. Perhaps most importantly, key producers, in particular Russia, have not imposed the kinds of export bans that helped trigger previous price hikes.

These were particularly damaging as the world has become more dependent for its grain on the Commonwealth of Independent States, which includes some of the world's biggest producers of wheat, including Russia, Kazakhstan and unofficial member Ukraine.

"Big producers have been battered by drought but they are honouring their export contracts," says James Walton, chief economist at food experts IGD.

"If Russia or central Asian countries were going to do something, they would probably have done it by now."

The Agricultural Market Information System, which was established last year and allows the world's major food producers to work off common data as well as providing a forum for discussion, has played an important part.

"Governments are shying away from restrictive measures; supplies are not as bad and inventories are not as bad," says Abdolreza Abbassian, senior economist at the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation.

"Recent experiences have made people a little over sensitive, but [the situation] does not look as bad [as 2008]".

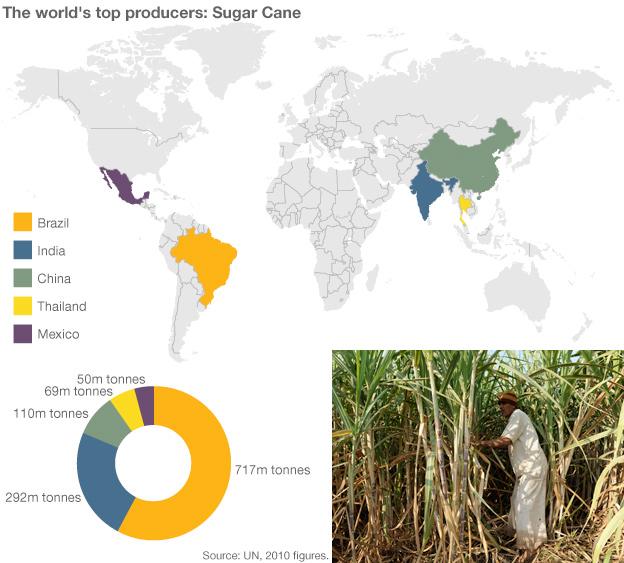

In fact, according to Mr Abbassian, there is no shortage of rice, despite patchy harvests, while inventories of wheat are good, and much higher than in 2007. Sugar production in Brazil has also been much better than expected, while China has generally had a good growing season, Mr Walton adds.

There is also less pressure on prices from biofuels, a "big factor" in the 2008 price spikes, Mr Abbassian says, when a record high for the price of oil drove demand for alternative fuels. Corn and sugar, for example, are used extensively in biofuels - in the US, 40% of all corn production goes into making ethanol. Not only is the oil price well below those highs, but the UN says fewer crops are being diverted towards biofuels.

Overall, then, fears of an impending food price crisis would appear to be exaggerated.

"There has been a lot of talk about food prices at the UN, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and the general feeling is we are not in the same situation we were in in 2008," says Marc Sadler, senior agriculture economist at the World Bank.

But while the chance of food prices returning to levels seen in 2008 and 2011 in the coming months may be slim, they remain at historically high levels, and the underlying factors driving them are here to stay.

Population growth and, more importantly, the rapidly growing middle classes in the developing world, are pushing demand for grain-intensive protein ever higher, while rising energy costs are pushing up the cost of supply. High food prices, therefore, are here to stay.

Long gone are the days of butter mountains and milk lakes as governments fundamentally rethink agricultural policy and cut back on subsidies to farmers.

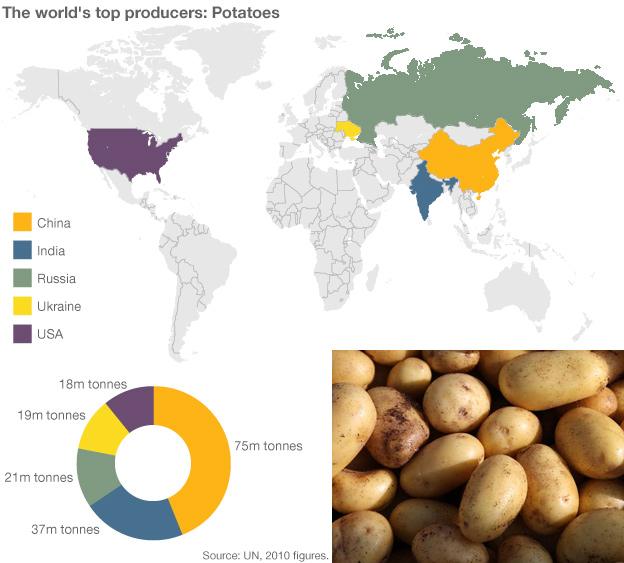

Global inventories have fallen sharply since the turn of the century as a result - wheat stocks are down by almost a third, rice by more than 40%, and corn by a half.

And these stocks are unlikely to increase. As Mr Sadler says, "even in a good year we just about produce enough food to meet consumption needs".

Margins, therefore, are getting smaller and supplies ever more susceptible to shocks, such as the severe droughts experienced in the past five years. And extreme weather patterns appear to be becoming more commonplace. Experts are wary of blaming climate change, but many believe rising temperatures are having a major impact on rainfall. If they are right, then unpredictable and more extreme weather is here to stay.

'Biggest challenge'

People in the developing are far more exposed to rises in the price of food

Those living in the developed West will be relatively unaffected, as produce in the shops is far removed from the raw commodity - wheat is a fairly small component in the cost of a loaf of bread, for example. In fact, the impact on the price of meat is more pronounced, as 5kg of grain are needed to produce 1kg of protein.

Even here, however, there has been a profound change in recent years, according to Mr Walton. "The era of cheap food which we take for granted is over. Food will continue to be available, but don't expect the price to go down," he says.

The impact on those living in poverty in the developing world - those who buy the raw ingredients to make their own produce, and who spend a far greater proportion of their income on food - is far, far greater.

"The global population will soon hit nine billion and everyone has to be fed. Making sure they are is the number one challenge of this century. This is not a question of can we, can't we? We have to," says Mr Sadler.

Dramatically cutting back on food waste, which currently accounts for a third of all food production, would be a start, but a huge increase in investment in global agriculture is also needed. If it fails to materialise, the consequences will be devastating.

- Published4 October 2012

- Published30 August 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published13 August 2012