UK productivity puzzle baffles economists

- Published

Though more people are hard at work fuelling fire, the UK economy continues to cool down

We are living through pretty strange economic times, and one of the most unusual aspects in Britain is what has been called "the productivity puzzle".

How can it be that more people are getting jobs when the economy is contracting? It means output per worker, or productivity, has fallen. BBC economics editor Stephanie Flanders has written about it several times.

It is an issue that has many economists scratching their heads, and it was highlighted once again by the latest jobs figures, showing another increase in the number in employment. The government agency responsible for the figures, the Office for National Statistics (ONS), has published its latest effort, external to get to the bottom of the puzzle.

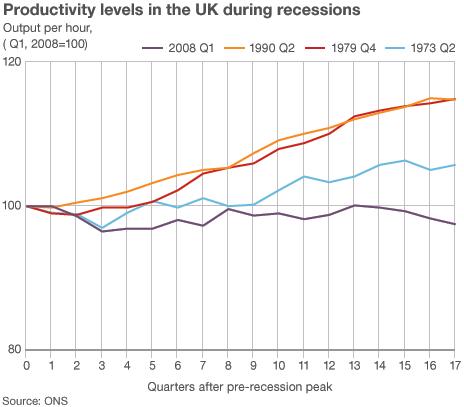

Productivity levels have remained relatively unchanged since the beginning of 2008. The difference between this and the three previous recessions is stark.

In the most recent episode, it fell further and recovered less.

It is the only one of these four recessions where productivity was still lower four years after the downturn began. It is true whether you look at output per worker or per hour.

When the data look strange, one possibility is that they are simply wrong, so the ONS have had a thorough review.

The agency acknowledges that measurement error cannot be ruled out, but the chief economist Joe Grice says that the GDP figures are broadly in line with information from tax revenue and private sector business surveys.

Moreover, he says, any revisions to the figures would have to be "out of all proportion to explain even a part of the productivity conundrum".

No surprise?

If the data are roughly right, then there really is a puzzle.

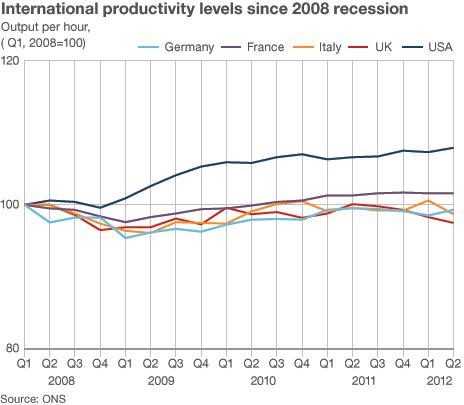

It is an issue for other European countries too, though - as the second chart shows - the weakness of productivity is most pronounced in the UK.

The ONS research concludes that there is no single factor that provides an explanation, but identifies several that may have contributed.

It comes as no surprise that the financial crisis itself is probably the cause of some of the damage.

Productivity in financial services and insurance was rising before the crisis at an annual 4.1%. Since 2009 it has fallen.

It is a sector that also affects the productivity of the rest of the economy, because of its role in providing finance for business investment.

During the boom years, it may have channelled too much into investments that turned out not to be very profitable.

Now, it could be struggling to finance new projects that might have high productivity.

Ben Broadbent of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee has floated a similar idea, external.

A flexible labour market is another candidate.

Hoarders

Firms have less need to fire people if pay rises are modest or if they are willing to work fewer hours.

Both have happened, though the downside is that a lot more people are working less than they would like.

There is one idea with a long history that the ONS seem less keen on.

It is called labour hoarding, where employers hang on to more workers than they need in a downturn, so that when there is a recovery they can respond quickly, without incurring the costs of hiring and training new people.

There is some evidence of this happening, but the longer it goes on, the more expensive it becomes for the employer.

And the theory is not much use for explaining new job creation, which has been strong.

Economists are puzzled by rising employment and falling output figures

So we have a puzzle, with some ideas of what is behind it.

But is it a problem? After all, it is the side effect of a more people having jobs than we might expect, and that surely is a very good thing.

Ian Brinkley of The Work Foundation agrees with that for the short term, but he says we need strong productivity in the long term to raise living standards and to maintain our competitiveness.

That calls for investment in physical and digital infrastructure and in skills. That is needed, he says, to give companies the incentive to invest, which they are not currently doing.

These are big questions for government and business to wrestle with.

But for now, perhaps it is a cause for some relief that the jobs market is not nearly as bad is could be.