Coal resurgence undermines clean energy commitments

- Published

- comments

Chinese coal production is rising despite a massive renewable energy drive

Coal, the dirtiest and most polluting of all the major fossil fuels, is making a comeback.

Despite stringent carbon emissions targets in Europe designed to slow global warming and massive investment in renewable energy in China, demand for this most ancient source of energy is greater than ever.

In fact, coal was the fastest growing form of energy in the world outside renewables last year, with production up 6% on 2010, twice the rate of increase of gas and more than four times that of oil. Consumption data paints a similar picture, while figures for this year are set to tell the same story.

There are a number of drivers behind coal's renaissance, many of which may be short lived. Others will push demand ever higher for decades to come.

Cheap alternative

Coal consumption in Europe, where governments have been at the forefront of the push to curb carbon dioxide emissions, has risen sharply in recent years.

Why? Because it's cheap, and getting cheaper all the time. Due to the economic downturn, there has been what Paul McConnell, senior analyst at energy research group Wood Mackenzie, calls a "collapse in industrial demand for energy". This has led to an oversupply of coal, pushing the price down.

It has also led to a massive surfeit of CO2 emissions permits, pushing the price of carbon, and therefore the cost of coal production, sharply lower.

Equally important, there has been a huge influx of cheap coal from the US, where the discovery of shale gas has provided an even cheaper alternative energy source. The coal has to go somewhere, so it's exported to Europe.

Finally, higher non-shale, natural gas prices are making coal an attractive alternative.

As Laszlo Varro, head of gas, coal and power markets at the International Energy Agency (IEA), says: "All parameters favour coal."

So much so that "coal is [now] being burned as the baseload fuel across most of Europe," says Gareth Carpenter, associate editor at global energy information provider Platts.

Germany's decision to scrap all nuclear power and build more coal-fired power stations can only boost production further.

Just how long coal's resurgence lasts depends to some extent on the global economic recovery and the ability of governments to implement a system that finally delivers a meaningful carbon price.

But, in the meantime, legislation passed more than a decade ago will severely curb coal production over the coming years, according to Mr Varro.

The full impact of the EU's Large Combustion Plant Directive, which is designed to reduce local air pollutants, but not in fact carbon dioxide, is about to be felt, meaning a number of inefficient coal plants will be decommissioned.

As a result, in five years, coal production capacity "will be considerably lower than today", says Mr Varro. The directive will do nothing, of course, to restrict cheap US imports.

Demand explosion

But whatever happens to coal production and consumption in Europe, spiralling demand for energy in Asia, in particular China, will ensure that coal production continues to rise significantly over the coming decades.

Population growth and the exploding middle classes will see to that - in China alone, demand for energy will triple by 2030, according to Wood Mackenzie.

China in particular is spending massive amounts of money on a renewable energy drive the likes of which the world has never seen - plans are in place to build almost 10 times the wind capacity of Germany, for example.

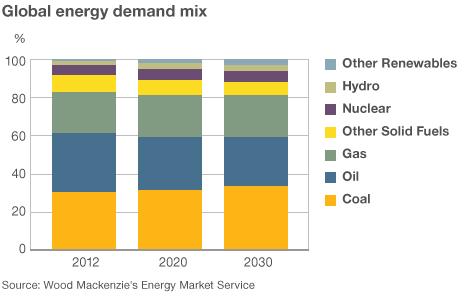

But even this will not be able to keep up with demand, meaning fossil fuels will continue to make up the majority of the overall energy mix for the foreseeable future.

And when it comes to fossil fuels, coal is the easy winner - it is generally easier and cheaper to mine, and easier to transport using existing infrastructure such as roads and rail, than oil or gas.

Its price is also relatively stable because, as Mr Carpenter points out: "Coal mines on the whole are located in relatively stable countries free from major geopolitical tensions."

For all these reasons, Wood Mackenzie forecasts coal production in Indonesia, currently the world's fourth-biggest coal producer, to rise by 60% by 2020, while China will import more than a billion tonnes by 2030, almost five times currents levels.

By this date, it expects global demand for imported coal to more than double, helping to push the fossil fuel's proportion of the overall energy mix even higher than it is today.

Carbon capture

Cheap energy is, of course, a vital ingredient in the continued economic growth of developing countries, but the implications of rising coal production for CO2 emissions and global warming are profound.

While China is currently running half a dozen carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects - which aim to capture CO2 emissions from coal plants and bury it underground - the technology is nowhere near commercial viability.

Demand for energy in China will more than triple by 2030, analysts forecast

As Mr Carpenter says, despite all the hype "it looks extremely unlikely that CCS technology is going to be deployed widely in the next 10 years or so".

The inevitable end result is rising CO2 emissions. According to the IEA, emissions from fossil fuels hit a record level last year, while total energy-related emissions and are due to rise by more than 20% by 2035.

"Why we aren't developing CCS for all we're worth is a mystery to me," says Prof Myles Allen at the school of geography and the environment at the University of Oxford.

"It is viewed as just one of a basket of solutions, but it's not - it's pivotal. Without it, nothing else follows."

And CCS lends itself perfectly to coal, precisely because it is such a cheap energy source.

Renewed urgency in developing CCS globally, alongside greater strides in increasing renewable energy capacity, is desperately needed, but Europe's increasing reliance on coal without capturing emissions is undermining its status as a leader in clean energy, and therefore global efforts to reduce CO2 emissions.

- Published18 November 2012

- Published9 August 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published14 September 2012