PPI: How did the bill ever get so big?

- Published

PPI mis-selling has led to a huge industry in compensation claims

Liz Woodford would never have been able to claim on her payment protection insurance (PPI) policy because she was self-employed.

But the training consultant, now aged 53, was sold the product all the same, when she successfully applied for a loan from her bank.

The bank has offered her £500 to cover the premiums she paid, along with the interest that would have built up if she had saved the money instead.

But that was still an amount that left her and her husband Adrian - a former financial adviser from Hampshire - "absolutely gobsmacked". They have rejected the offer, believing that she is due much more, and are pursuing their claim further.

The case, in a nutshell, offers a clue as to why the total bill that banks face for PPI mis-selling has almost reached a staggering £13bn.

In recent days, banks have been extending the amount they have set aside for PPI, admitting that they underestimated the scale of the scandal.

"It almost requires a separate page in every bank's accounts these days," says Justin Urquhart Stewart, director and co-founder of Seven Investment Management.

"Banks should be taking the worst option and writing it off."

Limits

A number of commentators suggest that PPI mis-selling has turned into the biggest financial scandal ever seen in the UK.

Yet, the product itself was always a valid proposition. It was the way it was sold that has left financial institutions with a bundle of compensation to pay.

Financial institutions sold PPI alongside loans, credit cards and mortgages. The insurance was to supposed to repay any outstanding loans if the borrowers fell ill or lost their jobs.

The attraction of selling it was clear for banks and their employees. It was, at its peak, the single biggest source of profit, with bigger margins than household or motor insurance.

The trouble was people were sold the policy when they did not want it or, like Mrs Woodford, were unable to claim on it. For example, they were self-employed or over the age limit set out in the terms of the policy.

Once that became clear, there was a huge legal battle, which the banks eventually lost. This led to a flood of compensation claims.

Surprise?

With the process now in full swing, banks are sending out 10,000 compensation payments and cheques a day.

The typical individual payout is £2,750, according to the financial ombudsman, but they have reached much higher levels in some cases. The BBC News website revealed in July how one businesswoman successfully claimed compensation of £65,000.

More than 2.5 million people have already received payouts, but others are lining up. The banks have started the process of writing to people who they think may have been mis-sold PPI, inviting them to make a claim.

The consumers' association Which? says that the industry was thought to have made a profit of £5bn each year from the sale of PPI - so question marks remain over whether the banks will ultimately lose out.

The cost of repayments, and processing those repayments, has certainly taken them by surprise.

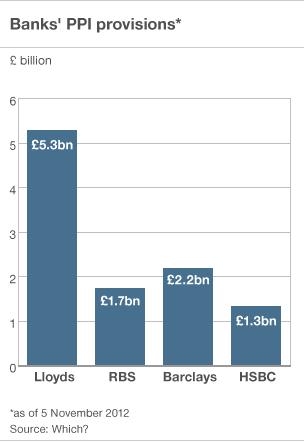

Antonio Horta-Osorio, chief executive of Lloyds Banking Group - which has the biggest PPI bill, said in the bank's last set of results, external that complaints were "above the level anticipated", and the final bill remained uncertain.

It set aside an extra £1bn to cover the PPI bill. Within the space of a week, Barclays also said it was setting aside a further £700m, RBS said it had earmarked a further £400m, and HSBC announced it had increased its provision by £223m.

So how could they appear to be so caught out by the scale of the issue? How could the architects be surprised by the size of the edifice that has been crumbling around them?

'Perfect storm'

There are many answers to that question, according to Martin Upton, head of the Centre for Accounting and Finance at the Open University.

PPI complaints make up nearly two-thirds of complaints to financial institutions

The first is a "sloppiness" that resulted in the fact that PPI was making money for banks and some of their salespeople. Consumer group Which? says that some bank staff were on an 87% commission for selling PPI.

"Incentivised staff and weak processes created a perfect storm," says Mr Upton.

Add to that the way in which the policies were being sold, which created the "conditions for mis-selling". They were sold as an add-on when customers were understandably focussing on their primary objective - getting a credit card, a loan or a mortgage.

Consumers might have had their eye off the ball at the time, but once they realised they had a claim for compensation, many were fully aware of their rights. That might in part be the result of the extra confidence gained from the last big subject of mass claims - bank overdraft charges.

Finally, Mr Upton argues, there could have been three big miscalculations by the banks - the size of the average payout, the number of claims that they could reject as unfounded, and the numbers who might not have realised they were mis-sold PPI but may eventually come forward.

They could push the final bill even higher, he says.

The number of claims has undoubtedly been pushed up by the activities of claims management companies. Spend any time watching commercial daytime television and you will see an advertisement from one of these companies.

These groups - who take a chunk of any eventual payout, as much as 25% - have been criticised by the banks for their approach. The "helicopter drop" of claims, without actually analysing the quality of these claims, has added to the bureaucratic costs the banks are facing. Some claimants never even had a loan, let alone a PPI policy, with the banks who receive demands for compensation, they say.

But the Claims Standards Council, the industry body for these businesses, says that the banks are suffering as a result of their own lack of action at the outset.

Anthony Sultan, who chairs the council's financial services group, says that claims management companies are simply filling the gap that banks have left.

"If they had held up their hands, there would not be all this activity," he says.

He also says that claims companies should have been allowed to charge the bank at the end of a successful claim, rather than the consumer. However, consumer groups point out that bank customers who think they have been mis-sold PPI can make a claim themselves.

There are, after all, a lot of other people doing exactly that.

- Published5 November 2012

- Published29 October 2012

- Published16 October 2012

- Published27 September 2012