Fed gives itself a new target

- Published

- comments

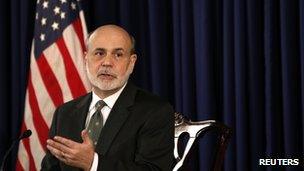

Fed chairman Ben Bernanke said he expects the unemployment rate to fall below 6.5% in 2015

The world's most important central bank has just given itself a new magic number: 6.5%.

That is the level the Federal Reserve now says it wants the US unemployment rate to fall to, before it will consider raising interest rates.

In a sense, this is just a logical continuation of the shift in policy announced in the autumn - which I wrote about at the time. But you have to wonder whether it will also turn out to be another step towards a post-crisis world of monetary policy, where the nominal rate of inflation is no longer the target of choice.

There are caveats to this promise, and it is not independent of what happens to inflation. In its statement, external yesterday, the Fed said that its forecast for inflation would also need to be below 2.5% for them to think about raising rates.

As it happens, the moment at which the Fed now expects unemployment to go below the magic 6.5% is the middle of 2015, which is more or less when they had previously said they would think about tightening policy. So you can see why the financial market reaction has been pretty muted.

It's also worth mentioning that the Federal Reserve already had an employment target: unlike most central banks, its mandate tells it to pursue not just price stability but full employment as well.

But still, it feels like an interesting moment: dangerous for the Fed, in the short term, perhaps, but also one that could open up new opportunities for other central bankers down the road.

At the Bank of England's Christmas drinks party last night, the reaction of senior officials and economists from inside and outside the Bank was almost universally scathing. They said the Fed had given itself another straitjacket - which it would live to regret.

Unlike inflation, unemployment statistics get revised. They tell you something about the strength of the economy, but they also tell you about the level of labour force participation at any given point in time: immigration, demographics - you name it.

A 6.5% unemployment rate might be consistent with one rate of growth this year - and another growth rate entirely in a few years' time. So, what looks like a good number now may look wrong in 2014.

All of these are reasonable concerns. But I can't help noticing that they are rather like the arguments that Bank and other UK officials have always given, when asked about policies or targets that are different from those currently being followed here in the UK. Other countries' targets are always either too rigid - or too flexible. Or sometimes, both. Ours, by a happy coincidence, seem always to be just right.

In a speech earlier this week, external, the next governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, said that numerical thresholds like the new ones provided by the Fed yesterday "exhaust the guidance options available to a central bank operating under flexible inflation targeting. If yet further stimulus were required, the policy framework itself would likely have to be changed."

At that point, he said, adopting a nominal (or cash) GDP target might then be the right way to go. Many others now agree.

Bank officials have been equally scathing about nominal GDP targeting - which, surprise surprise, turns out to be inferior, in their view, to the inflation target we have now.

I will go into the pros and cons of cash GDP targeting in my next post. But one early new year's prediction I would make is that we are going to hear more about it. And so are people at the Bank, when the new boss arrives.