HBOS collapse: Ex-bosses face calls for City bans

- Published

- comments

Financial regulators should consider banning three top HBOS bankers from senior roles in the financial sector, an influential committee has said.

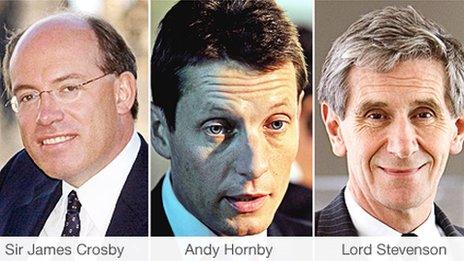

The Banking Standards Commission said, external former bosses Sir James Crosby, Andy Hornby and Lord Stevenson were guilty of a "colossal failure" of management.

HBOS collapsed in 2008, wiping out shareholders, costing thousands of jobs and forcing a £20.5bn taxpayer bailout.

On Friday, Sir James resigned as an adviser to investment firm Bridgepoint.

The BBC understands that he was asked to resign by the board of the private equity firm following the publication of the HBOS report.

So far, there has been no response from the three men to the findings.

Banking standards commission chair Andrew Tyrie says there was "a colossal failure of leadership" at HBOS

The Banking Standards Commission was set up to improve the UK's banking system following the 2008 financial crisis.

Its members are MPs, members of the House of Lords and the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Its report criticised the now-defunct City regulator the Financial Services Authority (FSA), saying the watchdog appeared "to have taken no steps to establish whether the former leaders of HBOS are fit and proper persons to hold the approved persons status elsewhere in the UK financial sector".

The Chief Secretary to the Treasury, Danny Alexander, said the government would consider whether more should be done to hold those responsible for HBOS's demise to account.

"Unfortunately, the regulatory regime that was in place at the time was nowhere near tough enough," he said.

"We're just taking action this week as a government to put in place a tougher, new regulatory regime to try and make sure that some of the mistakes that were made can't happen again."

The report, called An Accident Waiting to Happen, paints a damning picture of the management failures leading up to the collapse of the bank at the height of the UK's banking crisis.

It estimates that 96% of shareholder value was wiped out when the bank collapsed, costing taxpayers £20.5bn.

Lloyds Banking Group, formed from the merger of Lloyds TSB and HBOS in 2009, has since cut tens of thousands of jobs and remains 39% state-owned.

The banking crisis also precipitated the economic slump from which the UK is still struggling to recover.

The commission accused the bank of "reckless" lending policies that resulted in losses of £46bn.

Such losses would have led to insolvency, had the bank not been bailed out by the taxpayer and Lloyds TSB, the commission claimed.

'Too much risk'

The commission concluded that two former chief executives, Sir James Crosby and Andy Hornby, were mainly to blame for the collapse of the bank, together with its former chairman, Lord Stevenson.

"The primary responsibility for the downfall of HBOS should rest with Sir James Crosby, architect of the strategy that set the course for disaster, with Andy Hornby, who proved unable or unwilling to change course, and Lord Stevenson, who presided over the bank's board from its birth to its death," said the report.

"Lord Stevenson, in particular, has shown himself incapable of facing the realities of what placed the bank in jeopardy from that time until now."

In written evidence to the commission last December, Lord Stevenson admitted that the bank took on too much risk in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis.

The former head of wholesale banking at HBOS, Peter Cummings, was fined £500,000 and banned from working in senior financial roles by the FSA last year.

But the Commission expressed surprise that no-one else had been punished.

While the three executives saw their "Approved Person" status at HBOS lapsing, they did not face any further sanctions.

An Approved Person is someone who is permitted to carry out particular financial functions by the FSA.

"The FSA appears to have taken no steps to establish whether they are fit and proper persons to hold Approved Person status elsewhere in the UK financial sector," said the report.

Flawed strategy

The report said the strategy set by the board after 2001 "sowed the seeds of its destruction".

That was the year in which the Halifax and the Bank of Scotland agreed to merge, forming HBOS.

Its losses of £46bn included losses of £25bn in its corporate division, and £14.5bn in Australia and Ireland.

Senior executives of HBOS tried to blame the losses on the temporary closure of wholesale markets.

During the financial crisis, banks stopped lending to each other, resulting in their short-term supplies of funding drying up.

But members of the commission said they were disappointed by such explanations, as it was the lending approach that was to blame.

"This culture was brash, underpinned by a belief that the growing market share was due to a special set of skills, which HBOS possessed and which its competitors lacked," said the report.

"This was a traditional bank failure, pure and simple. It was a case of a bank pursuing traditional banking activities and pursuing them badly."

Lloyds Banking Group stressed that the relevant events happened before it owned HBOS.

"We continue to focus our efforts on rebuilding the group for the benefit of our customers, employees and shareholders," its spokesperson said.

Ray Perman, the author of Hubris: How HBOS Wrecked the Best Bank in Britain, said the commission's criticism was unusual in singling out individuals.

"For the first time, blame is squarely pinned on the people who deserve it - the chairman, the two chief executives," he said.

"What they did was to pursue a very fast growth strategy, regardless of the risk and they fooled themselves into thinking that their initial success was [because] they were better than everybody else, but eventually those risks caught up with them."

Failure of regulation

The commission said the FSA's regulation of HBOS was "thoroughly inadequate".

In the three years following the merger, it said, the regulator managed to identify some of the issues that would contribute to the group's downfall, such as its aggressive pace of growth and its reliance on wholesale funding, as opposed to using its own savers' deposits.

But it failed to follow through on these concerns and was too easily satisfied that they had been resolved.

From 2004 to 2007, the FSA was "not so much the dog that did not bark, as a dog barking up the wrong tree", claimed the report.

There was too much supervision at a low level and too much box-ticking, it said.

The report requires the FSA to answer nine questions about its failures. But since the FSA was abolished five days ago, on 1 April, it will not be able to do so.

Instead, its replacement, the Prudential Regulation Authority, said it would be studying the report, "to ensure that the lessons from the failings at HBOS have been fully learned".

A further report into the collapse of HBOS, started by the now disbanded FSA, will be completed by a new regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority.

- Published5 April 2013

- Published5 April 2013

- Published14 December 2012

- Published4 December 2012

- Published12 September 2012

- Published19 October 2012