Bangladesh textile workers' deaths 'avoidable'

- Published

Volunteers use the fabrics from the factory to try to rescue workers from the collapsed building

Bangladesh's workers who sew clothes for Western consumers are amongst the lowest paid in the industry anywhere in the world. This week, hundreds died as a result of an accident that campaigners say could have been avoided.

A building that housed suppliers of clothes to European and American retailers collapsed on Wednesday. According to one union leader, garment industry workers had been told to ignore the cracks in the walls and continue with work as normal.

"The deaths as a result of the collapsed building in Bangladesh were a tragedy but not an accident," says Murray Worthy from the charity War on Want. He argues that the level of neglect and lack of regulation in the industry led to the disaster at the factory.

It happened just five months after a fire at the Bangladeshi firm Tazreen Fashions in which more than 100 people were killed.

Campaigners say that the rapid expansion of the industry over the past few years played a large role in this incident.

It is a common occurrence for buildings to see illegal floors added, according to Sam Mahers from Labour Behind the Label. In this case, one minister alleged that the whole building was illegally constructed.

"Many of these buildings are a death trap, often with no proper escape routes. So while this incident is shocking it is not surprising," Ms Mahers says.

Labour Behind the Label, external is part of a campaign pushing for retailers to sign up to the Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Agreement.

It argues for action that includes independent building inspections, training in workers' rights and "a long-overdue review of safety standards". So far, Germany's Tchibo and America's PVH Corp (owner of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger) have signed it.

Employees in Bangladeshi factories are mainly women and conditions can be harsh, unions say. Although they are contracted to work eight hours a day, if an important order comes in workers are often forced to work up to 18 hours in a day, or on their day off, to finish the job.

Supervisors monitor them closely, even down to the length of their toilet breaks, the BBC's Bangladesh correspondent Anbarasan Ethirajan explains.

Competing on price

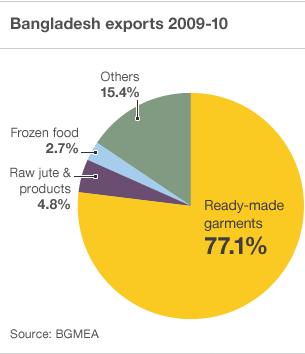

The textile industry is an important one for the country, accounting for 17% of its gross domestic product (GDP) and more than three-quarters of total exports - most of which head to Europe and the US.

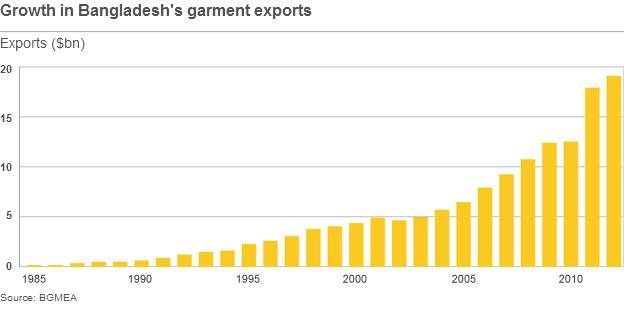

The amount of exports has increased dramatically over the past 30 years. In 1985 they were worth less than $1bn, but by 2012 the figure was nearly $20bn. That is mainly thanks to the country's cheap labour. Bangladeshi textile employees are among the lowest-paid of their kind in the world.

Sourcing Journal, a trade magazine for the textile manufacturing industry, points out that being cheap is the country's main way of remaining competitive against countries like China and Vietnam.

Companies are increasingly looking for cheaper alternatives and that is Bangladesh's only advantage as wages rise in China, says its editor Edward Hertzmann.

"It doesn't have a shorter lead-time nor does it produce any of the raw materials. The only way it can compete is on price. In some cases you get fabrics made in China and sent to Bangladesh to be stitched."

So far it is not clear which Western retailers the factory in question supplies. The British retailer Primark has acknowledged that it had a contract, as well as Canada's Loblaw and Denmark's PWT Group.

In a statement, Primark expressed concern for the families involved and said it "has been engaged for several years with NGOs and other retailers to review the Bangladeshi industry's approach to factory standards. Primark will push for this review to also include building integrity".

US supermarket giant Wal-Mart says it is "investigating across our global supply chain to see if a factory in this building was currently producing for Wal-Mart".

After the fire in Tazreen Fashions, which made clothes for the American company, the retailer terminated the contract with the supplier. Wal-Mart says it had subcontracted the work to the Tazreen factory without authorisation.

Bangladeshi rescue workers gesture for help

Buying power

Mr Hertzmann says that companies are starting to look more closely at their suppliers thanks to the number of campaigns on the issue and attention from the media.

"It won't change overnight, but more and more companies are sending people to factories to inspect them first-hand. But subcontracting out the work is often the problem and makes policing very difficult."

But what about the Western consumers who buy T-shirts for a few pounds or dollars?

Improving protection for workers in Bangladesh could lead to a small increase in prices, says Mr Worthy from War on Want.

"Our work suggests that most people in the UK would rather pay that [additional] cost than see this sort of human cost of cheap clothes," he argues.

But, he adds that while consumers should make their voices heard, the burden is on companies to change the way they operate, not on consumers to shop around.