Libor scandal: Can we ever trust bankers again?

- Published

Can we ever trust bankers again?

As Britain awaits a major report by the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards, the BBC's Business Production team, in partnership with the Open University, asks what went wrong with the system and can we ever trust bankers again?

About £132bn of British taxpayers' money has been spent bailing out the banks since the credit crunch in 2008 turned into an economic crisis.

But the crisis has exposed deeper problems with the banking industry.

The first episode of a three-part BBC Two series looks at the Libor scandal - a watershed moment that finally exposed wide-scale lying and cheating at the heart of the banking system.

Three banks - Barclays, Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and UBS - have together been fined more than £1.6bn by British and American regulators for fixing submissions to the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (Libor).

Marcus Agius, who resigned as chairman of Barclays as a result of the scandal, described the moment last June when he discovered what had been going on with Libor: "I was sick to my stomach because I realised just what an appalling thing it was and I realised what a serious implication it would have for the bank."

Several other banks are still under investigation. The outcry over Libor was so great that it prompted the setting-up of the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards, which is set to release a major report by the end of this month.

Libor, although little known outside banking circles before the scandal broke, underpins the financial system.

Mark Gilbert, of Bloomberg TV, says: "Everything you borrow, in effect, is influenced by Libor: every credit card, every mortgage, every car loan."

Daily a number of leading banks submit rates for 10 currencies and 15 lengths of loan, ranging from overnight to 12 months.

In each case, the four highest rates and the four lowest rates are ignored. The average of the remaining rates makes up the Libor rate.

Libor is embedded in more than $300tn (£192tn) of financial contracts, derivatives and loans.

As Gary Gensler, chairman of the US regulator, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, says: "This is the mother of all reference rates… [It's] about six times the world economy in orders of magnitude of dollars of contracts."

Fixing the System traces the cultural changes that took place in London's banks during the late 1990s and early 2000s, which many now identify as one of the underlying causes of the Libor scandal.

The Libor is set in London but controls trading in New York and all over the world

David Buik is a market commentator who began working in the City in the 1960s. "When I started," he says, "'My word is my bond' was the motto."

But Libor worked on trust and was entirely unregulated, so when greed and corruption crept in there were no safeguards.

It has now become clear that traders at several banks conspired to influence Libor by getting colleagues to submit rates that were either higher or lower than their actual estimate.

Even a tiny misrepresentation of an interest rate - say, from 2.6% to 2.7% - can make an enormous change to the profits being made.

Incriminating emails

The Financial Services Authority (FSA) trawled through the data records of traders at RBS, UBS and Barclays and found numerous incriminating emails, instant messages and phone calls that showed how Libor had been manipulated.

One message from a Barclays trader read: "Pls go for 5.36 again, very important that the setting comes as high as possible. Thanks."

Other messages showed how mutual back-scratching among traders was making many of them rich at the expense of the integrity of the market.

"Mate, yur getting bloody good at this libor game. think of me when yur on yur yacht in monaco wont yu," another broker wrote to a UBS trader.

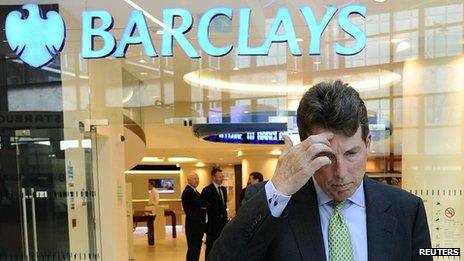

The Libor scandal brought to an end Bob Diamond's stellar career as boss of Barclays - the first bank to be fined by the regulators for Libor fixing.

Bob Diamond resigned as chief executive of Barclays last year after the bank was fined £290m for trying to manipulate Libor rates

Barclays was founded in the 17th Century by Quakers.

But in 1996, Mr Diamond, a charismatic and highly competitive American, took over and revamped the bank's investment arm, Barclays de Zoete Wedd (BZW), as Barclays Capital, turning it from a sleepy backwater into a bullish and risk-taking organisation.

In 2007, Barclays reported record profits of £7bn, largely thanks to a 300% increase in profits from Barclays Capital over the previous six years.

But Barclays Capital was at the heart of the Libor scandal.

Last June, Barclays was fined £290m. The deputy governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, said: "The message that the authorities were giving to Barclays was that they had to face up to the full reality of the situation and that it was untenable to think they could go on with the same management, almost as if not much had happened."

'No confidence'

Mr Agius recalls: "To put it simply, the governor [Sir Mervyn King], who had spoken to the chairman of the FSA [Financial Services Authority] and indeed had spoken to the chancellor of the exchequer, was delivering us a message that the regulator authorities no longer had confidence in our chief executive. A very, very strong message."

Mr Diamond was forced to resign a few days later.

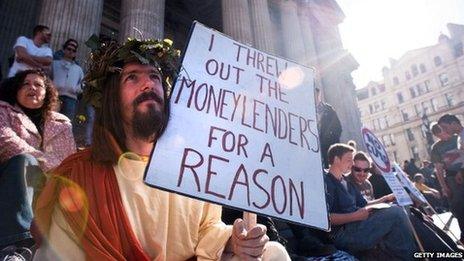

The economic crisis has fuelled widespread anger about the banking industry

Although banking has become something of a dirty word because of scandals such as Libor, there is no doubt that Britain needs a strong financial services industry.

So what do we need the banks of the future to be like?

Gillian Tett, assistant editor of the Financial Times, says: "Right now, in some ways, you have the worst of both worlds in the UK. You have a public who doesn't like the idea of banks making money, and frankly you have many politicians who don't like the idea of banks making money.

"They are asking a completely impossible task of the banks - to become profitable enterprises that don't need government support and yet, at the same time, they are reacting with horror when the banks actually try to do that."

'Rebuilding trust'

Sir Philip Hampton, chairman of the RBS Group, says: "We need our banks to be banks, if I can put it as crudely as that."

He says the public are angry: "They don't like the fact that the banks let them down and they don't like the fact that they had to bail them out and put that on top of all the other day-to-day issues - service not very good and value is often disappointing - and this is an industry that needs a lot of fixing and a lot of repairing in its relationship with its core customer base."

Antony Jenkins, who replaced Bob Diamond as Barclays chief executive, says: "We have to be realistic that rebuilding trust in the banking industry is going to take a long time and it's a product of what banks do, not what they say."

Jean-Claude Trichet, former president of the European Central Bank, says: "Now people would not accept, as they did in the past, to help considerably the financial sector because they have a lost a large part of their confidence. Greed cannot be dominating everything, because this is the ultimate recipe for catastrophe."

Watch Bankers: Fixing The System on BBC2 on Wednesday 8 May at 21:00 BST, or catch up later on BBC iPlayer.

- Published19 December 2012

- Published13 July 2012