Inside Facebook's green and clean arctic data centre

- Published

Checking in: If you are on Facebook anywhere in Europe today then that action probably went through the Lulea green data centre in Sweden

You've probably never thought about the electricity consumed by those Google searches, Facebook updates and all the other things you do online.

Maybe you should start thinking about it.

Data centres, the server farms that handle internet traffic, have emerged as voracious users of electrical power.

They already account for 2% of global power demand, according to research by the campaigning group Greenpeace, conducted several years ago.

The current figure is likely to be higher than that and is expected to rise exponentially in the future as computing increasingly shifts to the "cloud", meaning more stuff gets done over the internet and is stored and processed at data centres.

The trend is a big worry for environmentalists who are concerned about the implications for climate change.

The burning of fossil fuels to generate electricity is a prime source of carbon dioxide emissions - the main gas associated with global warming.

It is also a concern for data centre managers who must wrestle with enormous power bills.

Status update

Facebook has positioned itself as a leader in tackling both these aspects. The social networking giant has just inaugurated a massive new data centre in Lulea in Sweden, its first such facility outside the US.

The project has given the social networking giant an opportunity to burnish its green credentials.

The data centre runs entirely on renewable energy generated by nearby hydroelectric schemes.

Eye of the beholder: The Lulea data centre looks like any industrial unit from the outside - it's what's inside the counts

It is also designed to take advantage of the sub-arctic location.

A cold climate provides natural cooling for the literally tens of thousands of servers - Facebook won't say exactly how many there are - packed together in long aisles. This saves a lot of electricity.

If you post a status update, upload a photo or do any other kind of activity on Facebook in Europe, it will probably pass through the server farm in Lulea.

The plant isn't pretty. It is a vast warehouse-like structure, painted a drab grey, spread over 30,000 sq m - equivalent in size to four and a half football pitches.

Facebook's PR team seem to like these sort of statistics - another frequently repeated favourite is that 350 million photographs get uploaded onto the social network every day.

Facebook's global head of data centres Tom Furlong

With that kind of volume of data to handle, it is hardly surprising that Facebook needs a new shed to house some extra servers.

But why put it in a remote corner of northern Sweden?

"There are some must-haves and there are some nice-to-haves" says Tom Furlong, Facebook's global head of data centres, as he outlines the factors influencing the decision.

The must-have list is topped by guaranteed access to power and good internet connectivity.

This part of Sweden has access to two separate and very secure grid systems.

The last significant power outage was more than 30 years ago, and the area's hydro power capacity seems more or less limitless.

The nice-to-have list is dominated by the environmental arguments in favour of a climate-friendly power source that doesn't rely on burning fossil fuel.

Watertight: Lulea offers abundant hydroelectric power, from plants like the Akkats power station

There was also the chance to avoid using electricity altogether.

Servers are a bit like human beings in the tropics.

They like air conditioning and get hot and bothered if the temperature goes too high.

The advantage of a northern location like Lulea is not so much that is often cold but that it almost never gets very hot.

The predictable absence of warm days means the Lulea plant has 70% less energy intensive, expensive-to-run mechanical cooling capacity installed than the average data centre.

Facebook says it has a policy of sharing the knowledge it has acquired about how to make data centres efficient through a programme called Open Compute.

The information is open source and freely available.

Gentle poke

But environmentalists claim Facebook took a little persuading before it got serious about these issues.

Over a million users signalled their concern by "unfriending" coal on the social network in one recent campaign, says Gary Cook, senior IT advisor at environmental group Greenpeace International.

Chill wind: By locating the data centre in the far north of Sweden, Facebook uses far less electricity to cool servers

He claims this played an instrumental role in the company's decision to move towards using renewable energy in its data centres.

The first two facilities Facebook built, both in the US, were in areas where most of the power came from coal-fired generating stations.

Greenpeace believes this reflects a wider trend.

"Certainly in the US and in many other parts of the world, data centres are being drawn to dirty sources of electricity much like moths to a candle because it's cheap," says Mr Cook.

Power is cheap in states like Virginia and parts of North Carolina because power utilities have surplus capacity thanks of the decline of traditional industries.

Burning bright: Coal fired power stations are a major contributor to global warming

So they have offered data companies exceptionally low-priced deals.

"It's a big problem if we are simply taking the most advanced 21st century technology, and attaching it to dirty 19th Century coal technology," says Mr Cook.

Coal is a particular bete noir for environmentalists because it produces the highest carbon emissions.

Greenpeace says Apple, Facebook and Google, among the leading tech brands, have made significant progress in tackling these issues.

Google, for example, has become a major investor in wind power.

But online retailer Amazon has yet to get engaged, campaigners claim.

Every second counts

Many data companies are simply not in a position to take dramatic steps like insisting on power from wind farms or shifting operations to cold climates.

Options Technology runs a medium-sized data centre in an industrial estate in west London, along with smaller operations in 21 other locations around the world.

It has to stay close to its corporate clients, for example financial firms in the City, London's financial district, involved in high frequency trading.

The rapid fire nature of the transactions means even milliseconds count.

Having a data centre far way could put them at a disadvantage, even though digital signals travel at the speed of light.

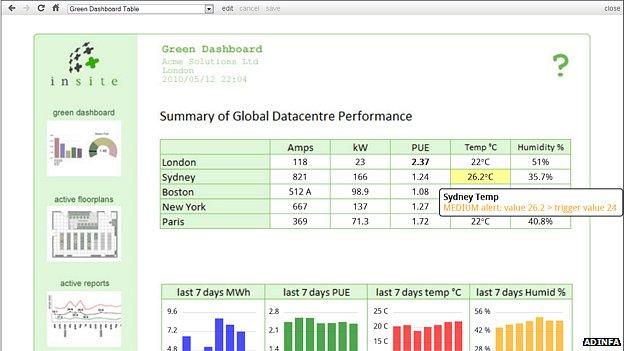

Feeling sensitive: The inSite software tracks the performance of a data centre using data gathered from multiple sensors

Glen Selby, the data centre manager at Options Technology, is focused on taking small, practical steps that added together have a significant impact in reducing electricity consumption.

Among them is attaching sensors to important bits of equipment and then monitoring them with software that gives staff easy to grasp information concerning safety and power consumption.

"One thing data centre managers aren't short of is data," explains Philip Petersen, director of software company AdInfa.

"Our inSite software helps mangers see the critical information they need to make better decisions in a way that is easy to understand."

I notice that his customer Glenn Selby glances at the screen of his smart phone as frequently as any teenager.

Presumably he's checking for alerts about his company's power consumption - not swapping Facebook messages with his mates.