Drone technology used for pilotless fighter aircraft

- Published

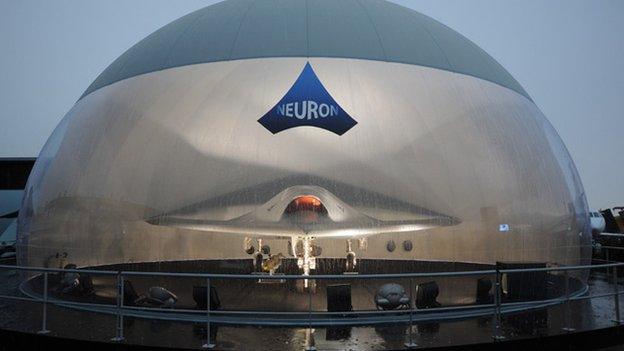

Under a huge semi-opaque dome and with heavy security in attendance, visitors to the Paris Air Show peer at a strange looking shape.

The matte black, almost featureless triangular aircraft is making its first public appearance, and the makers don't want people seeing too much of its advanced features.

But this object - the rather awkwardly-named nEUROn - could be the future of combat aircraft.

When a jet like the Rafale or the Sukhoi SU-35 shrieks overhead at the show, the watching crowds are left in awe at the skill and daring of the pilot.

Ever since the World War I, when aces like the Red Baron Manfred von Richthofen patrolled the skies, the fighter pilot has held a special place in the imagination.

But that status could now be under threat, because the next generation of combat aircraft may dispense with the pilot altogether.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, or drones, are nothing new, as their controversial use in Afghanistan and Pakistan has shown.

The drones - large and small - on display at the Paris Air Show

But drones have limitations, and are vulnerable to being shot down within seconds of going anywhere near properly defended airspace.

Enter the combat drone

One solution is to develop much larger machines, full-scale fighter aircraft capable of flying long distances at high speed.

They would be capable of bombing missions or tactical strikes, and able to defend themselves. And all without the need for a pilot.

A number of experimental "superdrones" have already been built. Among them are Northrop Grumman's X-47 and the BAE Systems' Taranis.

And then there's the spooky-looking nEUROn, being developed by a European consortium.

France's Dassault is the lead contractor in the six-nation consortium, with the other participants being defence companies from Greece, Italy, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland.

The nEUROn, which made its first flight at the tail end of last year, is an ugly beast, low slung and black.

Its rather bat-like appearance clearly owes a great deal to the Lockheed Martin F117 Nighthawk, better known as the original Stealth Fighter, and indeed it has been built using stealth technologies.

"It's a big one!" says Eric Trappier, chief executive of French firm Dassault Aviation. "It's the size of a fighter, with a bomb bay."

The aircraft has already done radar tests to assess its stealth capabilities, but a fully operational aircraft is unlikely to be ready until the end of the decade.

The use of unmanned aircraft in military situations has been controversial

Mr Trappier believes there is a clear role for unmanned aircraft to play in future conflicts, with fleets of pilotless planes being directed to targets by controllers on the ground, or from manned aircraft flying behind them.

"In some regions you have very dangerous missions, and the use of unmanned vehicles could be very useful. For example, the destruction of enemy countermeasures or missiles or whatever.

"It's mainly for the first day of war, where you don't really know what's going on in front of you, the UCAV (unmanned combat aerial vehicle) could be a good answer."

So could unmanned planes one day do the job better than a fighter piloted by an individual rather than a computer?

"Yes, in some types of mission it could be better. In some others, where you really need to have the pilot in the loop, well I think the manned vehicle will remain. So it's a kind of compromise between the unmanned vehicles and the manned fighters."

Serious mistakes

But manufacturers wont be able to develop them without opposition.

The use of existing drones has faced widespread criticism, largely because of the way in which they have been employed by the CIA in particular, outside the boundaries of conventional conflict.

But there have also been concerns that the operators of drones are too far removed from the battlefield to comprehend the seriousness of what they do and that mistakes can be made.

But according to Mr Trappier, the issue is not whether or not drones should be used, but how they should be operated.

"It's a matter of who is in charge, who is in command. You need to know what you are doing on the mission. Whether a human is in the aircraft or not, he has to be in the loop."

He says much of the criticism in the US is not about the use of drones, but about who is in charge: the CIA, the Pentagon, or the armed forces.

"You need to continue to operate UAVs as though you were operating a manned vehicle," he says.

That's fine in theory, but would it be the case in practice?

Given the amount of development money being poured into this industry, one suspects that in a few years time we will eventually find out.

- Published23 May 2013

- Published8 February 2013

- Published19 July 2012