How big are the government's infrastructure plans?

- Published

London's Crossrail took decades to leave the drawing board

"And now for the good news..."

That is the message the government would like to convey as it details how a third of the £310bn of investments scheduled in the National Infrastructure Plan, external will be allocated during the 2015-20 parliament.

George Osborne may have cut some departments to the bone in the latest Spending Review, but at least there will be new roads, power stations and broadband.

Eventually.

The chancellor was not short of hyperbole, promising "the largest programme of investment in our roads in half a century" and "the largest rail investment since the Victorian era", no less.

The reality is somewhat more nuanced.

Speed versus sexiness

First off, the government's big glamorous plans will not provide much immediate respite for an economy still barely in recovery.

Take the two most grandiose rail schemes.

HS2 - the High Speed link from London to Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds, external - is not due to start work until 2017, with completion pegged for 2032.

Crossrail 2 - a second new route under central London - has only just begun to go through a public consultation process, external.

Likewise, many of the long-heralded road improvements are far from getting started, for example the upgrade of the A14, which ferries trucks from Felixstowe container port to the Midlands.

Meanwhile progress on more "shovel-ready" but less high-profile projects has been painfully slow.

In November 2011, the RAC identified 96 road improvements, worth £11bn, as lacking in funding. It now says, external that a third of them are actually funded - or a quarter by value.

The audit office said it has "reservations" about the proposed rail link, as Richard Westcott reports

A big question mark also hangs over the very immediate, but decidedly unsexy problem of road maintenance.

It is the legal responsibility of local governments to keep about 90% of the network - all roads besides national highways - in good repair.

Yet the Spending Review cut the investment budget of the Department for Communities and Local Government by £1.7bn.

That comes on top of a 19% cut in the DfT's road maintenance, which had already led the Local Government Association to ask Whitehall for more money, external.

Planning more

Most of the projects announced by Danny Alexander, Chief Secretary to the Treasury, will probably not actually be paid for by taxpayers.

The cost of new offshore wind, gas and nuclear power stations and the upgrade of the national grid is ultimately borne by billpayers, while the cost of rail infrastructure mostly lands on farepayers.

But the government still plays a critical role, by guaranteeing loans and long-term prices for the companies that do the building and subsequent operating.

However, some query why the government doesn't just spend more of its own money, given how cheaply it can borrow these days.

"We have among the lowest interest rates in recorded economic history," says the economist Jonathan Portes, external.

"We have lots of... unemployed people and firms with spare capacity.

"There's never been a better time to borrow to invest."

He wants the chancellor to pump up the economy with an extra £20bn-£30bn of annual spending (about 2% of GDP) on infrastructure and homebuilding.

Spending less

Yet George Osborne did not announce any increase in infrastructure spending in Wednesday's Spending Review.

He stuck with the £50bn-52bn of yearly capital expenditure already laid out in the Budget he unveiled in March, external.

That "capex" covers direct Whitehall spending on building stuff, only a small proportion of which is actually infrastructure, mainly roads. The rest goes on housing, schools, hospitals, military bases and so forth.

That level of spending will do little to alleviate the moribund UK construction industry, which has shed almost half a million jobs since our current depression began in 2008.

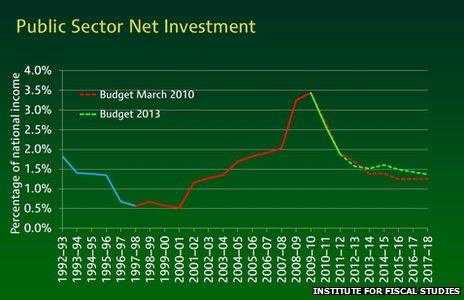

Mr Portes points out that planned investment, net of depreciation (wear-and-tear), is only half of the level it was at during the 2008-09 recession year.

Admittedly, 2008-09 is a high benchmark.

The then Chancellor Alistair Darling was desperately trying to prop up the economy at the time with a surge of spending. But he was already planning for it to drop off sharply after 2010 when Labour was voted out of office.

Common complaint

In the absence of more government spending, we are left with the planned reliance on private sector spending.

Yet planning is one thing. Delivery is another thing entirely.

For example, the government's flagship nuclear project, the Hinkley Point C reactor, has been held up by interminable haggling with EDF over price guarantees.

Similarly, investment in the factories needed to produce turbines for offshore wind farms - another big leg of the government's energy plans - have been stymied by uncertainty over government support, according to the renewables industry, external.

Plans for the UK's first new nuclear powered station for a generation have been given approval.

Both cases highlight an inherent problem in all infrastructure projects - their time horizon.

It's a common complaint.

"Rail plans are long-term. Governments aren't," says Gareth Edwards of the London Reconnections transport blog, external.

"At any time there are always critical projects waiting to be done, which you'll find in Network Rail's and Transport for London's strategic plans, but which are not currently funded.

"This is because they require large amounts of money at a future point in time, and money is generally only allocated in specific short-term blocks."

The planning uncertainty caused by short-sighted government policy has been cited by a London School of Economics study, external as the main impediment to infrastructure investment.

Just consider the vexed issue of London airport capacity as a case in point.

The National Infrastructure Plan therefore provides a helpful step towards reducing that uncertainty by looking five years beyond the next election to 2020.

It probably also helps that Labour is seemingly even more keen on public investment than the coalition.

That funding time horizon meant the Mayor of London could trumpet an "unprecedented" six-year funding package, external in the Spending Review.

But in truth what Transport for London and other infrastructure companies could really do with is to be able to plan for decades into the future.