Race between education and ignorance

- Published

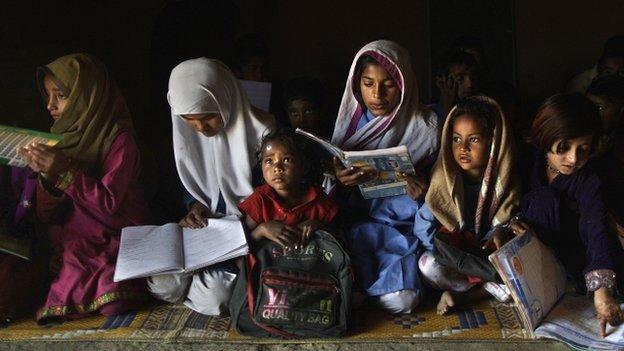

Makeshift school in a clay house on the outskirts of Islamabad, Pakistan

The tinderbox mix of high youth unemployment, lack of education and the threat of extremism is turning access to school into a "security issue", says Irina Bokova, director general of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

The volatile prospect of millions of uneducated, illiterate youngsters in developing countries, under pressure from the financial downturn, has brought an unprecedented political significance to the campaign to give every child a primary school education, she says.

Ms Bokova was speaking ahead of a speech later this week at the United Nations from Malala Yousafzai, who will call for all children to have the right to go to school.

The Pakistani schoolgirl, who will make her speech in New York on her 16th birthday, defied the bullets of the Taliban in defence of her right to an education.

But behind the optimism of Malala's campaign and the creation of an annual "Malala Day" is a much more complex global story, with failure as well as success.

In 2000, in the warm glow of a new millennium, world leaders pledged that universal primary education would be achieved by 2015. No child would miss out on the basics of schooling.

Head and heart

After an initial surge, progress stalled and achieving the target in the next 18 months now seems unlikely.

"By 2015, it's impossible," says Ms Bokova, the Paris-based head of Unesco.

Unesco head, Irina Bokova, says there has been "huge progress" in school places

But she says that rather than being a cause of pessimism, the pursuit of the target has brought "huge progress". There were 108 million children out of school when the pledge was made; the most recent figures suggest this has fallen to 57 million.

"If the right strategies are in place, and you put your head where your heart is, then things can be improved. In Afghanistan in 2000 only 4% of girls were in school, now there are more than 70%."

Ms Bokova says that another positive outcome has been a much stronger recognition of the importance of measuring the quality of education, rather than simply counting heads going into a classroom.

Among the more sobering discoveries has been that many pupils have spent years in school but remained functionally illiterate.

So in the autumn, Unesco is planning to produce a new set of global metrics to measure what's actually being learned in primary classrooms around the world. "It will give a global understanding of what quality education means," says Ms Bokova.

It remains unclear whether there will be more targets after 2015, but anything that emerges will be more about quality of education, rather than simply volume of places.

Funding gap

Ms Bokova says the financial crisis delivered a major blow to achieving the goal of universal primary education. Donor countries pulled the plug and left an "alarming gap" in funding.

In sub-Saharan Africa there remains a shortage of 1.7 million teachers.

Malala Yousafzai on her first day back in school earlier this year

But despite this gloom, she says that the financial crisis has given education a "paradoxical" political importance.

Youth unemployment is a major threat in many countries and education and training are seen as vital investments.

"Education is now becoming in some cases a security issue," she says, with examples such as Afghanistan, Iraq and across the Middle East, where there is huge pressure to provide education to promote stability and democracy and to avoid extremism.

"The same is true of big emerging powers. In Brazil, the government recognises that the education system is one of the biggest challenges as it moves forward to a competitive economy and an inclusive society."

The social tensions of deepening inequality and a lack of social mobility are also shaped by decisions about education systems, she says.

Economic and political stability are now inextricably linked to improving education, says the Bulgarian-born Unesco director general.

"Education is becoming the key issue now in discussions about overcoming the economic crisis.

"But how are we going to make this happen? Budgets and international aid are shrinking.

"We try to convince countries that if they want to invest in coming out of the crisis, then invest in education."

'Malala Day'

Another barrier to getting all children to school is a lack of fair access, particularly for girls.

Ms Bokova says it's not acceptable for countries to hide behind ideas of "cultural differences" or "tradition" as a reason for discriminating against girls.

Malala Yousafzai has become a powerful emblem.

Terror attacks on education targets: student bus bombed in Quetta, June 2013

"One event can spark a huge reaction and understanding and I think it was the case with Malala," she says.

"It was a stunning example of courage and a desire to learn."

And she says that getting more girls into school is the single most important goal.

"It's not just a human right, it's what is needed to have normal societies. If a girl goes to school, she is less likely to have an early marriage, she will have healthier children, she'll find it easier to earn an income, she's less likely to be subjected to violence, less likely to have an early pregnancy.

"There are so many advantages, healthier communities, less violence, more economic growth. It has such an incredible multiplying effect.

"This is the best thing that could happen to humanity."

Biggest problems

The pledge for education for all has also highlighted where the problem is most acute.

A meeting organised by the UN in April brought together eight countries - Bangladesh, DR Congo, Ethiopia, Haiti, India, Nigeria, South Sudan and Yemen - which between them have about half the children in the world who are missing out on school.

It was an unprecedented attempt to systematically work out what has been going wrong.

A minister from the DR Congo said that about 60% of those missing out on school did so because of the cost of school fees with the other 40% blamed on armed conflict.

In Ethiopia the problem was identified as being focused on rural communities and lack of access for girls. In South Sudan it was a lack of trained teachers and a low level of school participation among girls.

In Nigeria, which has the most children out of school, the difficulty was not necessarily about money, but was caused by low participation among girls in some areas and problems with "infrastructure" about providing teachers. Weaknesses in state authorities delivering the plans of the national government were also blamed.

The country has also seen brutal attacks on schools. Secondary schools in Nigeria's north-eastern state of Yobe were ordered to close this week after a massacre in which suspected Islamist extremists killed 22 students.

Ms Bokova says that there is now a willingness among such countries to recognise what needs to be changed.

Despite the failure to make the 2015 deadline, she says the attempt has shown the international community what can be achieved. Countries such as India and Ethiopia have taken substantial steps forward.

This has disproved the feeling that "education is too complex, too costly and it takes too long to show results".

But there is no escaping the harsh truth that millions of children, born a decade after the world promised universal primary education, still won't have even the most basic access to school.

It's been possible to launch hundreds of satellites and put a spacecraft on Mars, but not to put children into classrooms a few hours south of Heathrow.

"In many cases we have failed, but it shouldn't discourage us. We're winning the argument."