Bank links interest rates to unemployment target

- Published

- comments

Bank of England governor Mark Carney: "People need clarity over interest rates"

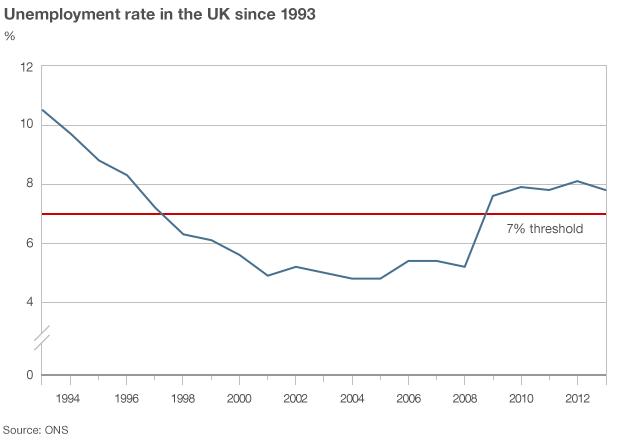

Bank of England governor Mark Carney has said the Bank will not consider raising interest rates until the jobless rate has fallen to 7% or below.

Mr Carney said he expected this would, external require the creation of about 750,000 jobs and could take three years.

The UK unemployment rate currently stands at 7.8%.

The governor told the BBC: "We need to provide as much clarity and as much certainty about the path of monetary policy."

Speaking to chief economics correspondent Hugh Pym, he said such guidance was needed "so that people… at home, people who are running businesses, across the UK, can make decisions - whether they are investing or spending - with greater certainty about what is going to happen with interest rates".

He added: "In effect we are saying - 'we are providing guidance on what could happen with interest rates'."

The governor told our correspondent that such a move was needed now "when the recovery is just gathering some steam", and when financial markets might have therefore been expecting an adjustment in interest rates.

Mr Carney said that the 7% unemployment figure was not a target, but a point at which the Bank of England would re-examine interest rates.

The Bank's guidance is subject to three provisos; breaching any of them would sever the link between interest rates and unemployment levels.

These so-called 'knock-outs' are:

CPI inflation is judged more likely than not to be at or above 2.5% over an 18-month to two-year horizon

inflation looks like it could get out of control in the medium term

the Bank's Financial Policy Committee judges this stance poses a significant threat to financial stability

'Renewed recovery'

Mr Carney said that until the unemployment threshold was reached the Bank would not cut back on its £375bn asset purchase programme, known as quantitative easing (QE).

The move sees the Bank of England joining both the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank in providing so-called "forward guidance" on interest rate policies.

Recent economic figures and surveys have suggested the recovery in the UK economy is picking up pace.

On Tuesday, official figures showed manufacturing output surged in June, while surveys have also indicated gathering strength in the service sector and housing market.

While upbeat on the prospects for the UK economy, Mr Carney said it had not reached "escape velocity" yet.

"A renewed recovery is now under way in the United Kingdom and it appears to be broadening," he said.

"While that is certainly welcome, the legacy of the financial crisis means that the recovery remains weak by historical standards and there is still a significant margin of spare capacity in the economy, this is most clearly evident in the high rate of unemployment."

'Confidence boost'

John Longworth, director general of the British Chambers of Commerce, said the forward guidance would reassure firms.

"This will give businesses a much-needed confidence boost when looking to invest, as they know that any plans will not suddenly be derailed by a hike in interest rates," he said.

Business lobby group, the CBI, echoed this sentiment, saying greater interest rate certainty and clarity from the Bank should provide a shot in the arm for business and households.

But Alan Clarke, director of fixed income strategy at Scotiabank, said unemployment could drop below 7% - the rate that would trigger a re-evaluation of interest rates - well before the Bank of England expects.

"Our knee-jerk reaction is that 2016 is a rather conservative assumption," he said. "Our working assumption was that level of the unemployment rate could be reached at least a year earlier."

The possibility of an earlier-than-expected rise in rates lifted the pound on the currency markets, with sterling rising by more than a cent against the dollar to $1.5458.

'Significant caveat'

There had been widespread expectation that Mr Carney would commit the Bank to the new strategy.

With short-term interest rates already at historic lows, the aim is to reduce longer-term interest rates.

Knowing interest rates could remain low, potentially for years, gives banks and mortgage lenders the ability to "lock-in" customers at lower rates for longer.

Stocks fell after the announcement, with Joshua Mahony, research analyst at trading firm Alpari, saying markets had been underwhelmed by Mr Carney's announcement.

He added that rules about the circumstances in which the strategy would be terminated had brought a "significant caveat to the table".

'Dismay'

The Chancellor, George Osborne, welcomed the move.

"I agree with you that forward guidance can play a useful role in enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy and thereby support the recovery," he said in a letter to the governor.

Shadow chancellor Ed Balls also applauded the decision but warned it would be "very important that the MPC [Monetary Policy Committee] stays vigilant to inflationary risks".

George Osborne: "I very much support the decision... [People] are going to have greater certainty that interest rates are going to stay low for longer."

But pressure group Save our Savers expressed "dismay", saying it would cause further hardship for savers and pensioners, while continuing to favour borrowing at the expense of saving.

Meanwhile, Graeme Leach, chief economist at the Institute of Directors, said guidance "doesn't really take us forward" and called for radical supply side reforms to bring on a surge in productivity.

Supply side reforms include lower tax rates and less regulation.

The Bank of England's quarterly inflation report, external was more upbeat about economic growth than it had been in May.

It presents its forecasts as a range of possibilities rather than a specific figure, but predicted accelerating growth for the rest of this year, with its central forecast being for growth of about 2.4% in two years' time.

It also forecast that the consumer price index (CPI) measure of inflation was likely to be at its target rate of 2.0% during 2015.

The rate of CPI inflation increased to a 14-month high of 2.9% in June, up from 2.7% in May.

Housing bubble?

At the press conference where the new policy was announced, members of the Bank's MPC were asked whether they were concerned by claims the government's Help to Buy scheme was fuelling another housing bubble.

The Help to Buy scheme was launched in April 2013 and allows borrowers to take an equity loan from the government worth up to 20% of the price of newly built homes.

That, in turn, enables homebuyers to put down a deposit of as little as 5%.

From January next year, it will be extended to help buyers of existing housing.

Critics claim the scheme is artificially inflating house prices, leading to future problems when the support is withdrawn.

But Bank of England chief economist, Spencer Dale, said it was important to keep the size of the scheme in perspective.

"The current run rate of [Help to Buy] is something like 3% or 4% of total housing transactions," he said.

"It's done its job in terms of encouraging new house building, but the idea that it is somehow fuelling a housing boom doesn't stack up in terms of the numbers."

- Published7 August 2013

- Published7 August 2013

- Published7 August 2013

- Published12 February 2014

- Published7 August 2013

- Published5 August 2013