The low cost technology saving premature babies' lives

- Published

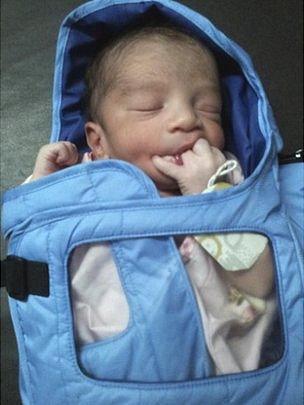

Tiny lives: Premature babies have very little body fat and are unable to regulate body temperature

Every year more than 20 million babies are born prematurely or with low birth weight - and an estimated 450 of them die each hour.

Yet most of these deaths could be avoided by simply keeping them warm.

"A new-born baby wailing can generally be heard outside the room - even across the hallway. But not my baby. Mine can only whimper," says Jayalakshmi Devi.

She's standing outside the neo-natal intensive care unit (ICU) staring at the glass box where her baby son is kept.

Born too soon, her baby boy weighs less than 1.2 pounds (0.54kgs). Doctors have given him around a 40% chance of survival.

Having lost two babies already, Jayalakshmi didn't want to take a chance this time. After delivering her child in a rural healthcare centre three hours outside Bangalore, she brought the baby to the state run hospital in the city.

Women often give birth at home in rural areas and only bring them to hospitals when there is a critical need

At Vanivilas hospital, the neo-natal ICU sees scores of premature babies. Most are born at home, in far off rural areas and are brought here in critical condition.

Row after row, the transparent boxes create warmth to hold the tiny, bare-bodied babies with only an oversized diaper around them. Some of the babies are small enough to fit into your palm.

Life-saving warmth

A baby's body temperature drops as soon as it is outside the controlled environment of the mother's womb. So just after labour, it's important to regulate the temperature.

But premature babies have very little body fat, so they are unable to do that.

The babies need incubators to help keep them alive - equipment which state-run hospitals like this one often cannot afford.

So, GE Healthcare created the Lullaby baby-warmer, to help to save lives in a country that has the highest rate of pre-term baby deaths in the world.

Small packages: Premature babies kept in the low-cost incubators in the neo-natal ICU in Vanivilas hospital in Bangalore

Low-cost innovation

It was developed in Bangalore and launched in 2009. The baby warmer costs $3,000 (£1,900) in India, 70% cheaper than traditional models.

The design includes pictorial warnings and colour coding, so that even illiterate rural healthcare workers can operate the machine.

The Lullaby warmer also consumes less power than most incubators, which means cost savings for the healthcare centre.

"Where better to make a baby warmer than here - India produces a baby nearly every second," says GE Healthcare's Ravi Kaushik.

He believes India is an ideal innovation centre when it comes to products like this, because 70% of the population is rural and 30% is urban, and within this you all different stratas of society.

"So you can have very great world class hospitals that want and require world class medical equipment that America or Europe would require. But at the same time there is a population in rural space that would require same kind of medical attention," says Mr Kaushik.

"So when you design a product, you have to cater to the entire plethora of needs. That allows you to almost hit the entire world because India is a small representation of that."

Engineers at GE's technology centre are stripping down lifesaving, high tech medical devices of all their frills to understand how to create products that are affordable.

This project is now widely quoted as an example of "reverse innovation".

This is where large global companies design products in developing markets like India and then take the successful creation back to international markets to sell.

After success in the domestic market, GE now sells the warmer in more than 80 countries.

Bundled up

While this works for healthcare centres on a budget, it still needs continuous electricity to run.

The Embrace warmer is a low-cost sleeping bag-like product designed to be durable and re-usable

But go further down the population pyramid, and the problems get more complex.

Women in villages give birth at home and have little access to basic healthcare or electricity.

For them, keeping babies warm means wrapping them in layers of fabric and hot water bottles, or putting them under bare light bulbs.

Many of them don't survive.

But now a low cost baby bag is saving thousands of young lives. Called the Embrace, it emerged out of a class assignment at Stanford's Institute of Design in 2007.

Four graduate students - Jane Chen, Linus Liang, Naganand Murty, and Rahul Panicker - were challenged to come up with a low-cost incubator design that could help save premature babies born into poverty.

The team created a sleeping bag with a removable heating element.

Using high school physics, they used phase-change material (PCM), a waxy substance that, as it cools from melted liquid to solid, maintains the desired temperature of 37 degrees celsius (98.6 F) for up to six hours.

The end product looks like a quilted sleeping bag that is durable and portable. It requires only 30 minutes of electricity to warm up using a portable heater that comes with the product.

More importantly for mothers, it allows for increased contact with their child, unlike traditional incubators.

So it also encourages Kangaroo care, a technique practiced on newborn, especially pre-term infants, which promotes skin-to-skin contact to keep the baby warm and facilitate breastfeeding and bonding.

The infant warmer costs about $200 to make, is inexpensive to distribute, and is reusable.

All wrapped up: The Embrace warmers are donated to mothers in impoverished communities

Embrace is a non-profit venture. The product is not sold, but is donated to impoverished communities in need.

The invention is thought to have helped save the lives of more than 22,000 low birth-weight and premature infants.

Taking the programme forward, the organisation has developed a new version designed for at-home use by mothers. The model has been successfully prototyped and is currently undergoing clinical testing in India.

The organisation has also set up educational programmes to address the root causes of hypothermia.

"We provide intensive, side-by-side training to mothers, caretakers, and healthcare workers," says Alejandra Villalobos, director of development at Embrace.

"We develop long-term partnerships with local governments and non-profits in every community where we work.

"We believe that increased access to both technology and education is necessary to achieve our ultimate vision: that every woman and child has an equal chance for a healthy life."