'We may never get big industry here' in Templin

- Published

Chancellor Angela Merkel grew up in Templin, in eastern Germany

"After the Berlin Wall came down people here had high hopes," says Volker, a touch mournfully as we chat over a glass of beer in his living room.

"But not all of them have been realised. Far from it in fact."

Volker is a handyman and former shipyard worker. He lives in Templin, a small town in the Uckermark.

It is a region of eastern Germany best known for its dark forests and deep lakes, which once formed part of the Communist German Democratic Republic (GDR).

Templin's main claim to fame is that this was where Germany's Chancellor, Angela Merkel, grew up.

She arrived as a young child in the 1950s, was educated in the local school and remained here until her university days.

On the surface, it is a very pleasant town. A few tourists stroll through its medieval walled centre, admiring the brightly painted half-timbered houses and neatly decorated cafes that line its cobbled streets.

But step beyond the brown stone walls of the old town and a very different picture emerges.

The outskirts are dominated by dilapidated and rather grim concrete apartment blocks dating back to the Communist era.

An area of parkland lies overgrown and neglected, while nearby the derelict shell of the Hotel Allende stands abandoned, its windows smashed and its walls covered in graffiti.

The truth is that Templin is in trouble.

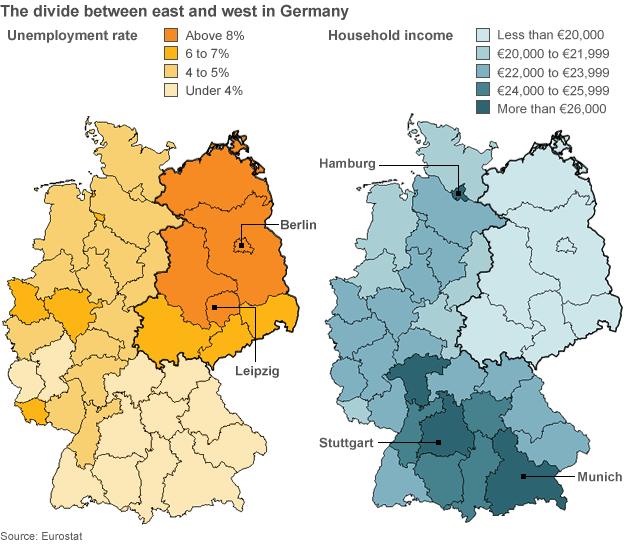

The "zweite Wirschaftswunder", the new economic miracle some experts have proclaimed in Angela Merkel's Germany, has passed this region by.

Unemployment here stands at 16%, more than three times the national average.

Young people are abandoning the area for the bright lights of Berlin and other prosperous cities, and the population is ageing rapidly as a result.

'It was very run down'

The problem is that when the GDR collapsed, so did most of the industry in the region. It was unable to cope in the shiny new world of market forces, and so far that industry has not been replaced.

Templin has to accept it is unlikely to attract big business, says Mayor Detlef Tappert

Detlef Tappert, Templin's mayor, believes it may never be.

"We've got to accept that we're limited by the poor road networks.

"That makes it unlikely that we'll ever get big industry around here.

"What we try and do is support as best we can smaller industries in the region."

Yet one industry in Templin is thriving. On the edge of a forest a couple of miles beyond the town walls is the factory of Holzindustrie Templin, a sawmill and wood trading business.

It is one of the largest mills of its kind in Europe and employs 90 people. By Templin's standards, it is big business.

Inside, huge beech and oak trunks are shunted back and forth on rollers, as a series of giant laser-guided saws cut them down into timber planks, destined for sale in markets such as India and China.

The plant was once owned by the East German government. It was bought by two West German entrepreneurs in 1992, and since then more than 30m euros ($40m; £25m) has been spent on turning it into a state-of-the-art facility.

"It was very run down back then," says Christine Wurfel, whose father was one of the investors, and who now helps to run the business.

"There were very few workers, no facilities and no competitive production facilities. There weren't even any paved roads."

Holzindustrie Templin looks very different today. It is clear that huge efforts have been made both to modernise the business and to make it look modern.

It even generates its own power, by burning waste wood.

Changing attitudes

I ask Ms Wurfel why she thinks other investors have not followed her family's example.

"To be successful here you have to be really committed to this region," she tells me.

"You have to think long-term, decades ahead. You have to educate your own workforce.

"We did all of this, and despite the ups and downs imposed on us by different state policies, I think we've managed quite well."

The biggest problem, she says, is the changing attitude of the Brandenburg state government towards forestry.

It was once supportive, but now she thinks it is more concerned with environmental protection at the expense of her industry.

I ask if she thinks the business has benefited from being in Mrs Merkel's home town - and whether the chancellor has shown any interest in the local economy.

"No, not at all. I know she visits here sometimes, but we have not had any interaction with her, or any political interaction with her," she says.

And that is the remarkable thing about visiting Templin.

People here are clearly proud of Mrs Merkel, the small town girl who rose to the top and now heads Europe's most powerful economy.

'She rarely comes to Templin'

But at the same time, there seems to be a general feeling that they have been left behind and that the fate of the region - or indeed that of eastern Germany as a whole - is not a priority for her.

"She is a great politician," says handyman Volker.

"She rarely comes to Templin now, but when she does you don't really notice she's here.

"There's no big fuss about it. On a personal level that makes her seem very likable. She even goes shopping in the local supermarket.

"But I don't think Templin has benefited in any big way through its association with her," he says.

I ask if he plans to vote for Mrs Merkel in the election on Sunday. He pauses for a moment.

"No comment," he says with a chuckle.

- Published18 September 2013

- Published16 September 2013

- Published13 September 2013

- Published12 September 2013

- Published12 September 2013

- Published11 September 2013

- Published10 September 2013