Have UK businesses missed the train in Ethiopia?

- Published

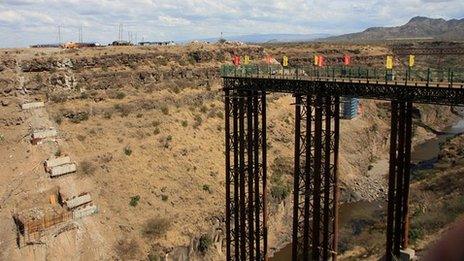

The railway will link Ethiopia's capital Addis Ababa with Djibouti on the coast

Across the Ethiopian countryside 2,000km (1,243 miles) of railway is being built, the first phase of an endeavour to create a new 5,000km network.

Currently no British companies are involved, despite Ethiopia approaching the UK for assistance at the start, and the project being constructed according to official UK railway industry standards.

The centrepiece of the new rail system is the planned line between Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, and the neighbouring country of Djibouti.

So far about a quarter of the preparation work has been completed on this key route, which will enable land-locked Ethiopia to access Djibouti City's port on the Horn of Africa coast.

Meanwhile in Addis Ababa, construction of the Light Rail Transit (LRT) - similar to London's Docklands Light Railway - will give the capital its first mass transit system, transforming mobility in a city where nearly 90% of the population travel on foot, or by squeezing in to buses and taxis.

Both projects began in early 2012 and are joint ventures between the Ethiopian government and Chinese companies that successfully bid for the $3.3bn (£2.2bn) Addis-Djibouti contract, and the $500m LRT project.

A quarter of the railway track has already been laid

"I was hoping that by now there would have been more input from UK companies," says John Pearson, a British railway engineer with more than 40 years' experience.

Mr Pearson has since 2009 been technical adviser to the Ethiopian Railway Corporation (ERC), which is overseeing both projects.

He describes the present lack of British involvement as unfortunate and something that needs to be addressed by UK government.

Ethiopia turns to UK

In 2008, ERC general manager Getachew Betru visited the UK to explain Ethiopia's railway infrastructure plans.

Mr Pearson, who met Mr Betru during his visit, decided to move to Ethiopia after being impressed by the project.

Also, Mr Pearson hoped to promote British businesses within the Ethiopian railway sector.

However, no other UK interests followed him to participate in what he calls "one of the most important transport infrastructure projects for Ethiopia and East Africa".

The British embassy in Addis Ababa tried on many occasions to promote business opportunities offered by the railway infrastructure's development, according to Dessalegn Yigzaw, its trade development manager.

But Ethiopia still has an image problem, Mr Yigzaw says, with UK companies failing to believe business is possible while associating the country with famine and drought.

Ethiopia's railway is forecast to carry almost 25 million tonnes of freight by 2025

Mr Pearson echoes this sentiment, saying that UK companies remain nervous about participating in major projects in sub-Saharan Africa.

While he acknowledges some companies have had bad experiences, he says this should not hold others back as the UK has capacity-building skills Ethiopia needs.

Insufficient short-term profit margin is most likely putting UK companies off coming to Africa, says Manaye Ewunetu, managing director of London-based ME Consulting Engineers that specialises in Africa and the Middle East.

"It might not look like a mistake now," Mr Ewunetu says, "but in the long term it could look like a mistake."

All tracks lead to Djibouti

The Addis-Djibouti corridor has always been an important strategic route for Ethiopia.

The new 781km route eastward to Djibouti - offering the shortest distance from Addis Ababa to a seaport - is expected to haul 11.2 million tonnes of freight in its first year of operation in 2016, rising to 24.9 million tonnes by 2025.

The new line could be carrying passengers by 2016

Passenger trains are also planned to run on the line, which will wind around Ethiopia's highland plateau and vertiginous topography before dropping 2,500m to sea level.

Ethiopia's varied terrain poses challenges for the route's railways engineers, and will do for those involved in phase two, constructing railway lines from Addis to Axum in the north and to Moyale in the south on the border with Kenya.

But the benefits could be worth the pain, according to Mr Betru, providing relief to rural areas in times of drought, linking Ethiopia's economic hubs, and benefiting other countries such as South Sudan that wants to export its oil via Djibouti's port.

Mr Getachew says there is every chance that a first-class train ticket to Djibouti will be available by early 2016.

Others say such a timeline is optimistic and if achieved it may well be at the expense of quality and sustainability.

Completion of the LRT by the proposed end date of 2015 is more likely, they say, although this will not come without friction. Construction is causing havoc for businesses and traffic alike in the capital.

All not lost for UK investment

Ethiopia's terrain has posed challenges for the track's engineers

It is not too late for UK businesses to get involved in the second phase of Ethiopia's railway infrastructure construction, especially as some say first phase costs could rise sharply, weakening the assumption that Chinese companies offer best value.

Also, financial constraints on UK companies investing in Ethiopia are easing due to the active involvement of the Export Credits Guarantee Department (ECGD), the UK's official export credit agency, according to Mr Yigzaw.

And investment does not have to be just in Ethiopia. Railway construction is also going on in the Republic of Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda, Libya and Egypt.

"Africa is a great market," Mr Ewunetu says. "But unless you are on the train, you will miss out."

- Published24 October 2013

- Published24 October 2013