India stock markets buck global trend

- Published

An Indian trader monitors share prices on his computer screen

As the global markets flopped at the end of last week under the repeated threat of the Federal Reserve removing its support for the US economy, one market decided to go the other way - India.

The fact that the BSE index, or Sensex, often ignores global equity trends is not the point. In fact the last time the Fed looked as though it was going to "taper" off its $82bn (£59bn) quantitative easing programme Indian stocks were knocked sideways along with every other emerging market and the rupee collapsed.

By September it had fallen 20% since the beginning of the year to an all-time low against the dollar. The reasons were threefold - an escalating current account deficit, a too-big budget deficit and the prospect of foreign money being sucked back to the US as interest rates there started to move back up.

Foreign investors

So what has changed, and why has the prospect of "tapering" not created a rerun of what happened in September?

Instead foreign investors seem to be content to hang in there - the rupee hit a five-week high on Thursday and the stock market is flirting once more with all-time highs.

If there is one event that changed sentiment it has to have been the appointment of Raghuram Rajan, as governor of the central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

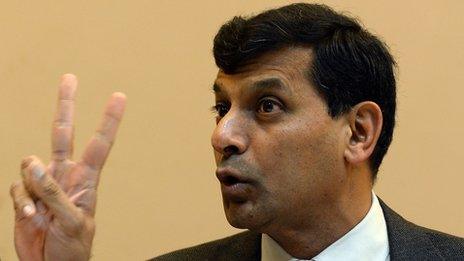

Raghuram Rajan has been called a rock star by the Indian media

It's not often in economics that being handsome plays much of a part, but he was given a rousing welcome in the Indian press for his laid back "rock star" good looks, suave self-confident style, and almost as an afterthought his economic credentials:

chief economist at the IMF

Professor of finance at the Graduate Business School at the University of Chicago

economic adviser to the Indian Finance Ministry

What's more he made the most of it. Where his predecessor, Duvvuri Subbarao, had been vilified for attempting to put up interest rates, Mr Rajan's two interest rate hikes have been greeted with giddy enthusiasm by almost everyone. He coupled it with steps to liberalise the banking sector and expand financial services to the hundreds of millions of Indians who remain unbanked.

And more reforms are in train - he's quoted as saying: "There are so many low-hanging fruit in the economy that if we only pluck them we can accelerate growth substantially."

Confidence

Mr Rajan's greatest achievement then has been to restore a measure of confidence, and with it has come a measure of stabilisation for the rupee and a 20% rise in the Sensex as investors came back to the market.

He's remarkably sanguine about India's public finances too, where he says the deficit is shrinking - down from 73.2% of GDP in 2006-07 to 66% in 2012-13.

Just before he became governor he pointed out in a paper that most of the debt was held domestically.

External debt, he said, "stood at only 21.2% of [gross domestic product], much of it owed by the private sector, while short-term external debt is only 5.2% of GDP".

"India's foreign-exchange reserves stand at $278bn, enough to finance the entire current-account deficit for several years," he added.

So much for the question of confidence. Is there any reason though to have greater confidence in the fundamentals of the Indian economy? Well, economic figures do seem better - just. Economic growth came in a touch better than expected, at 4.8% over the last quarter.

The two latest Purchasing Managers' Index surveys on services and manufacturing show improvement for the first time in months.

Manhur Jha, senior global economist at Standard Chartered, believes the current account deficit is changing for the better too.

"This was one of the reasons why India was hit so hard when the Federal Reserve appeared to be about to taper its support for the US economy.

"India was among a number of countries like Turkey and Indonesia with the biggest current account deficits that suffered the worst. But it is now improving."

Muddling through

Standard Chartered now believes India's current account deficit in 2014 will be half what it was in the year to March 2013, at about 2.5% of GDP or $45bn. The weaker rupee is helping of course and it is no accident that the best performers on the Sensex have been the big exporters.

The final link in the chain is politics. The Sensex has been given a lift by what is being seen as a suggestion that come the May elections, the government may be stable enough to push through more reforms.

Exit polls at the state elections this week indicated Narendra Modi and the opposition, the Hindu Nationalist BJP, may be making significant gains.

Madhur Jha said: "It is likely there is going to be another coalition government but the polls do suggest the opposition is gaining ground and the markets would be happy with a stable coalition that is able to push through reforms, to end bottlenecks in infrastructure and encourage the private sector to invest in rail, electricity and roads. But they won't be doing that until May, and until then - the economy will have to muddle through."

Muddling through may not be enough to keep the Sensex up at all-time highs, and no-one is forecasting any return to the heady days of 8% annual growth, but there is enough in the political-economic mix to suggest the gloom over the Indian economy may now be shifting.

- Published4 December 2013

- Published3 December 2013

- Published29 November 2013