Fed tapers, now the hard part begins

- Published

- comments

It was one of the most anticipated moves in monetary policy.

Yet the Fed trimming its monetary stimulus - cutting its cash injections by $10bn to now inject $75bn per month - still managed to surprise.

Despite the timing surprise, US stocks - the Dow and S&P 500 - closed at record highs on the so-called "taper" finally happening.

But the hard part begins now.

The cutback is of US Treasury purchases from $45bn to $40bn per month and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) from $40bn to $35bn.

The evidence suggests that MBS has been more effective at lowering mortgage costs by increasing liquidity in the housing market than buying US government bonds has been in lowering long-term interest rates. In any case, both are being cutback from the start of next year.

Looking to the future

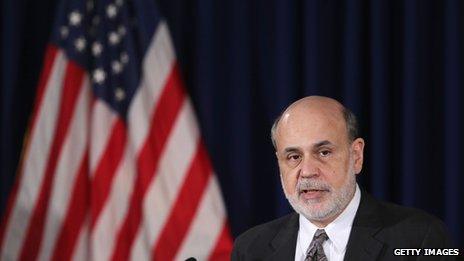

It was Bernanke's last press conference even though he steps down at the end of January since next month's FOMC doesn't have one.

Announcing the decision to taper starting in January 2014 while at the same time setting out interest rate expectations seemed to have worked as stocks were cheered in the U.S. That's also likely due to better economic signs.

After all, Congress has seemingly managed to overcome a fiscal impasse that could have seen a repeat of the government shutdown and debt ceiling debacle early next year.

Plus, crucially, nearly 200,000 jobs per month have been added on average in the past three months. But, even at that rate, it will take years for employment to fully recover.

US stock markets reacted well to the Fed's decision to cut back on stimulus

Crucial communications

Thus, the importance of the press conference to set out the "separation principle" between cash injections or quantitative easing (QE) and interest rates.

For many, of course, the quantity and price of money are closely related. It's just that in the jargon, we are at ZIRP (zero interest-rate policy).

It's one of the extraordinary things about all of this cheap cash - how low inflation is despite the Fed injecting $4 trillion (yes, that's nearly double the size of the entire UK economy whose GDP in dollar terms is around $2.5 trillion).

Using the Fed's preferred measure of inflation, prices are rising by just 0.7%. This is considerably below their 2% target and in spite of the Fed balance sheet at about a quarter the size of the entire US economy, which is the largest in the world.

This is why Mr Bernanke and other central banks such as the Bank of England espouse "forward guidance", so that QE is viewed separately from interest rate rises.

Once the cash injections end for the Fed, like they have in the UK, then their forward guidance maintains that rates will remain low for a long period of time until the economy recovers. The big question here is whether they will be believed by markets who determine the rate at which they will lend to the government over the longer term.

After all, there are those who have little faith in ZIRP and anticipate the inflation will take off. If so, then they are unlikely to lend money at a low nominal interest rate since their real return is the difference between the nominal rate and inflation down the line.

This will be the hard part - to convince markets to keep rates low in accordance with the central bank's base rate.

It is, after all, the markets that determine the borrowing costs for not just governments, but for all of us. This is particularly the case since the US wholesale money market is an important part of funding banks alongside deposits. So, if funding costs start to rise in the US, then Europe and other advanced economies will feel the impact.

The Fed's decision will have an impact on overseas economies like India's

Overseas impact

There are also implications for emerging economies.

Money has left these economies since Mr Bernanke first mentioned tapering back in May, which I have written about before.

The cost of money certainly matters for these economies, some of which have become indebted to cheap foreign money. For the first time since the financial crisis, more emerging economies have been downgraded than promoted by the rating company Fitch last year, for instance.

For all of us, the big question is when will rates rise and get back to normal.

I recently spoke to Richard Koo of Nomura who has written about Japan's debt trauma and how a generation of Americans wouldn't borrow after the Great Depression because they were so relieved to be freed from debt. Interest rates stayed at ZIRP for over 20 years.

Times are different now, though five years from the crash, the Fed is still printing cash to the tune of $75bn per month. There is likely still some way to go before things go back to normal.

Finally, on the timing of taper, one of Mr Bernanke's answers was perhaps telling.

He listed forward guidance alongside asset purchases (cheap cash injections) alongside his crisis management as his legacy. His swansong before leaving office was to set in train "taper" and the most demanding test for forward guidance - which is whether markets will believe that rates will stay low once QE ends.

In his own words, Mr Bernanke said: "I hope I live long enough to read the textbooks."