Why gold lost its lustre for investors

- Published

A couple of years ago, so much scrap gold was coming through the door of Baird and Co that the company could barely keep up.

It is the biggest producer of gold products in the UK and Baird, based in east London, uses scrap metal supplied by pawnbrokers, traders and industry.

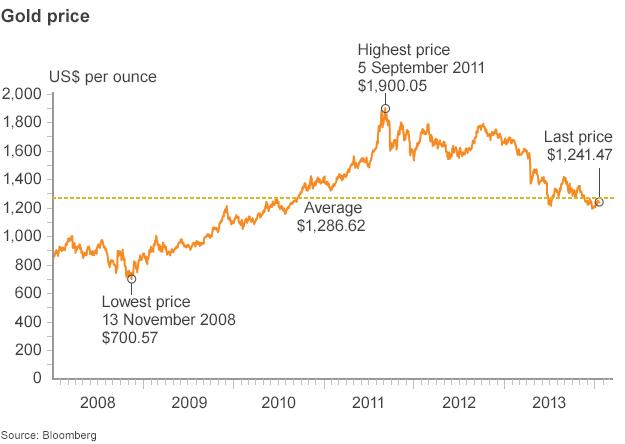

On the commodity markets, gold prices soared 170% between late 2008 and 2011.

On the High Street, "cash for gold" traders were springing up and, with a recession taking its toll on household finances, plenty of people were willing to sell jewellery.

And at Baird the furnaces were running flat out.

"Two, three years ago there would probably have been a [gold] melt every two hours every day," says Tony Dobra, executive director at Baird.

"In 2009 it was a lot of small guys, variations on cash for gold - we must have seen 200 variations on cash for gold."

During the boom years his company was taking in more than 10 tonnes of scrap gold a year and melting it down to gold bars, coins, rings and other products.

But last year the supply of scrap jewellery began to slow down.

"Since the summer of 2013 we've seen a lot of the smaller guys just disappear," says Mr Dobra.

And it's not just the small players that got into trouble in 2013.

Profits collapsed at the UK's biggest pawnbroker Albemarle and Bond and it was forced to melt down its own gold just to stay in business.

So what happened? Well, on the commodity market prices for spot gold tumbled 28% in 2013.

That plunge was prompted by better news on the global economy, particularly in the United States.

As a result the US Federal Reserve started hinting that its policy of pumping hundreds of billions of dollars into the economy could be coming to an end.

There was always concern that Fed policy could cause inflation and that supported gold prices which have long been seen as protection against rising prices.

But with that support gone, gold prices slumped.

'No return'

So what does 2014 hold for gold prices?

David Jollie, analyst at Mitsui Precious Metals, says: "Our view is mildly positive, mildly bullish, so we're expecting higher prices but not hugely higher prices.

"We're not expecting a return to where we were a year and a half ago."

He thinks that most people who wanted to get out of their gold investments have probably done so.

In the boom years Baird was melting 10 tonnes of scrap gold annually

Patricia Mohr, commodity market specialist at ScotiaBank in Toronto, holds a similar view. She sees average prices this year of $1,270 per ounce, which is roughly where the price finished in 2013.

"Gold prices probably bottomed in late June of last year," she said.

But she says forecasting the price of gold is tricky as it is mainly driven by speculators on the commodity markets, rather than the supply and demand for physical gold.

Huge demand

So if the financial markets have driven down the price of gold, where does that leave firms that deal in the real thing?

Many gold firms, including Baird, are now focusing on Asia, where demand for gold as an investment and for jewellery is growing.

In fact, some buyers there consider gold to be relatively cheap.

"The big buyers of physical gold are in Asia, they are in developing markets, they are in places like China, particularly last year where demand was huge," says Mr Jollie.

In the first nine months of last year, Chinese customers bought almost 800 tonnes of gold jewellery, bars and coins - a 40% jump on the same period in 2012.

For India the figure was 716 tonnes, up 19%, according to figures from the World Gold Council.

'Giant magnet'

The next biggest nation in terms of gold buying was Turkey with 159 tonnes.

Baird is opening an office in Singapore to meet demand from Asia

To meet that demand, Baird and Co has recently opened an office in Singapore and ships pallets full of gold from London to East Asia.

"Despite China being one of the world's largest gold producers, it's now the world's largest gold importer and consumer as well," says Mr Dobra.

"It's like a giant magnet."

- Published30 January 2014

- Published30 December 2013

- Published28 November 2013