UK debt and deficit: All you need to know

- Published

MPs and experts will use different numbers for what appear to be the same thing

If the politicians in charge can't get it right, what hope for the rest of us?

In a party political broadcast last year, David Cameron claimed that "we are paying down Britain's debts".

As you will soon see, we most certainly are not.

And the prime minister is not alone. Last month, Chancellor George Osborne claimed the deficit had fallen by a third since the coalition came to power in 2010.

But in December, shadow chancellor Ed Balls said the deficit had not come down.

So who's right and what's what when it comes to the UK's debt and deficit?

Debt

This one is pretty straightforward, kind of.

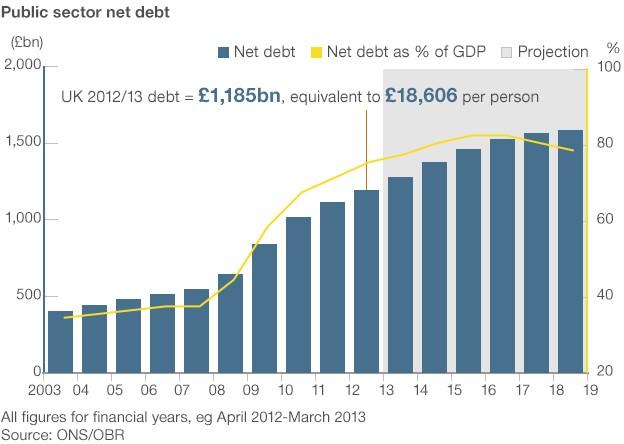

Debt simply refers to the amount of money owed by the UK government. This is the debt that has been built up over many years by many governments - the running total if you like.

But be careful with the word total. The accepted and widely used figure for debt is actually the net debt of the UK; in other words, the total debt minus the government's liquid assets.

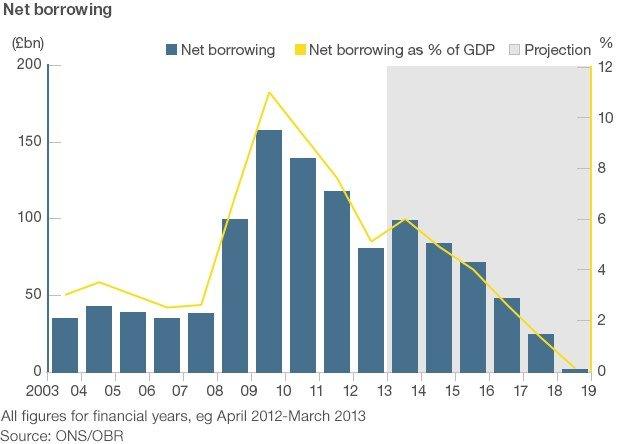

As the chart below shows, debt has increased massively in recent years, doubling to more than £1tn in the past five years, largely due to the financial crisis and resulting recession.

An easy way to compare debt levels across different countries is to express debt as a percentage of total economic output, or GDP, which is why you'll hear commentators regularly talk about the debt-to-GDP ratio. Obviously this has risen sharply since 2007.

And, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility, the UK's stock of debt will keep on rising for a number of years. So if anyone tries to tell you that UK debt is falling, they are wrong.

Deficit

Now things start to get a little trickier.

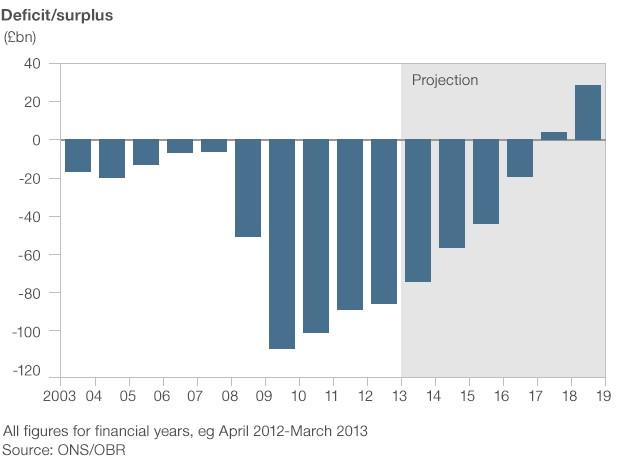

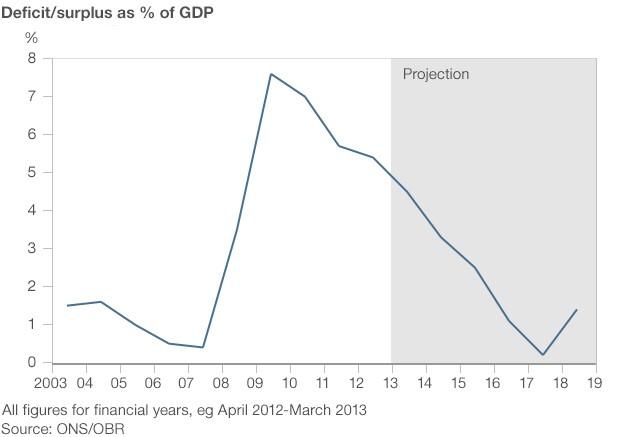

The current budget deficit, or surplus, is the difference between the government's everyday expenses and its revenues; in other words, between what it spends and what it receives. In recent years, it has spent a lot more than it receives, so we are used to hearing about a budget deficit.

But if the government spends less than it receives, then of course it would run a budget surplus. This may seem a strange concept in today's economic climate, but between 1998 and 2001 we had four straight years of surplus. In fact, there was a surplus every year between 1947 and 1974.

Both the government and opposition are pledging to return the current budget to surplus in the next Parliament.

And there is a direct link between the current budget and debt. If the government runs a deficit, it is effectively overspending and, therefore, in most cases adding to the overall pile of debt. By running a surplus, the government can chip away at this pile.

All fairly straightforward. The thing is, when most politicians and commentators talk about the deficit, they are not actually talking about the budget deficit. Helpful, isn't it? There are some exceptions - as a former Treasury man, Mr Balls talks about the current budget - but most are actually referring to government borrowing (see below).

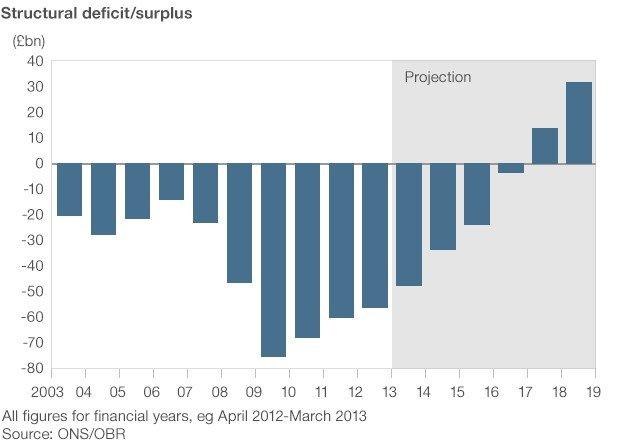

Structural deficit

Now for the difficult bit. You will hear some politicians, particularly from the Conservative Party, talk not just of deficits, but of structural deficits.

The structural deficit is basically the current budget deficit, adjusted to strip out the cyclical nature of the economy. You would expect, for example, the budget deficit to narrow when the economy grows after a sluggish period. The structural deficit attempts to exclude the effect of this recovery.

In other words, the structural deficit is the bit of the deficit that remains even when the economy is operating at full tilt. Or put another way, it's the underlying deficit that is not directly affected by economic performance.

Borrowing

Borrowing is... well, borrowing. Strictly speaking, borrowing and deficit (current budget) are not the same thing.

The two are linked, of course, as one covers the other, but the government doesn't just borrow money to pay back the deficit. It also borrows to invest.

The current budget covers everyday expenses - welfare payments, departmental costs etc. But the government also makes big investments, such as infrastructure projects, that are not included.

If the government is running a deficit, it may make investments on top of this, and will therefore need to borrow to cover both.

For example, in the calendar year 2007, the Labour government borrowed £37.7bn, of which £28.3bn was invested in big projects (the balance of £9.4bn represents the current budget deficit). Conversely, in 2013, the Conservative-led coalition borrowed £91.5bn, with just £23.7bn invested.

A neat, if rather simplistic, illustration of the different philosophies of the right and left in UK politics, some might say.

In the case of a surplus, the government may still need to borrow to cover its investments. This is why a current budget surplus does not automatically lead to a fall in overall debt, as borrowing to invest might be greater than the surplus. Equally, if government assets grow by more than the current budget deficit, then the deficit would not lead to an increase in overall debt.

Anyway, the important thing to remember is that, although there is a difference between the current budget deficit (or surplus) and government borrowing, for simplicity's sake commentators will usually quote borrowing figures when talking about the deficit. And you can see why, as they cover big infrastructure investment as well as everyday spending. After all, it is all borrowed money that needs to be paid back, and that adds to the overall pile of debt.

So there you have it. The next time you hear politicians arguing about debt levels and deficits, you'll hopefully be in a better position to decide who's right and who's wrong. Just bear in mind they could be talking about different things, so don't be surprised if they're both right. Or wrong.