Italy's economy: The mountain Matteo Renzi must climb

- Published

One of Matteo Renzi's priorities will be to boost Italy's economic growth

For the new Italian government, led by Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, the big task will be to breathe new life into the Italian patient.

It is the third largest economy in the eurozone, one that has underperformed since the single currency was established 15 years ago, and for a decade before that.

So how big is the challenge?

Italy is not alone in having problems in the eurozone, but some comparative data shows Mr Renzi's new team will have a serious task on their hands.

If we go back to the turn of the century and look at the total growth achieved up to last year, we find that both Germany and France have managed 15% (using GDP figures for whole years up to 2013).

That yields an average of about 1% per year, which is not impressive.

Spain, even after the financial crisis in which it was one of the eurozone's casualties, is 18% ahead of where it was in 2000, and Ireland is more than 30% up.

Italy's total growth in the same period is approximately nothing. In fact, using figures from the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) database, the economy was slightly smaller last year than it was in 2000.

That makes Italy unique in the eurozone.

Italy's economy has shrunk slightly since 2000

Behind the jobs figures

Ahead of the financial crisis, Italy's economy did expand, albeit modestly, and then went into reverse. Switching to quarterly data, it is still 9% below the peak it reached before the crisis.

It is also a pretty dismal picture if you look at GDP per capita, which gives a somewhat rough and ready indication of living standards. In Italy that measure fell by nearly 7% between 2000 and last year. Greece, Cyprus and Portugal have also seen falls, but not so large.

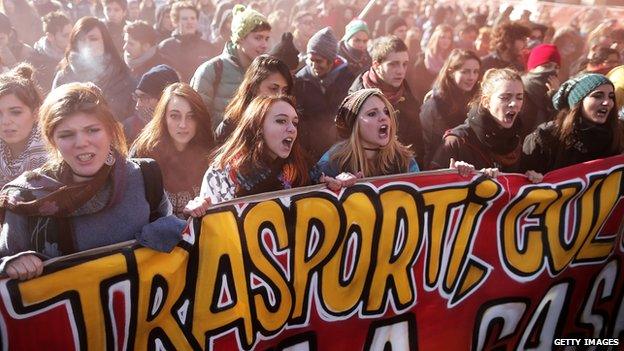

Unemployment in Italy is high, at 12.7% in December. That is above the eurozone average, but less than half the dismal figures for Greece and Spain.

But the Italian jobs situation is arguably worse than the unemployment figures suggest. People who aren't looking for work are not counted as unemployed.

Instead we can look at the percentage of the working age population who do have jobs. In Italy that is 55.6% (in the third quarter of last year).

That's a long way below the eurozone average of 63.8%. Spain and Greece are the only eurozone countries with a figure below Italy's.

Italian unemployment is arguably worse than official statistics suggest

Big debtor

Italy's general economic weakness lies behind another problem - government debt.

There are several ways of measuring it - in cash terms or as a percentage of GDP and either gross or net, which involves deducting state-owned financial assets.

Italy is one of the largest eurozone debtors on all these measures, though it doesn't take number one spot on any.

To take one example, according to IMF estimates the Italian government's gross debt is now more than 130% of annual GDP. Greece is much worse.

Sluggish growth makes this problem harder to tackle. It reduces tax revenue and stronger growth would mean that any given debt in cash terms would be a declining burden relative to GDP.

Debt is the total that the Italian government owes. It reflects what you might call the sins of the past, debts built up by previous governments. Its current annual borrowing needs are not especially high compared to the rest of the eurozone.

And there is one measure where Italy is, believe it or not, best in the region.

If you take out interest payments, you get what is called the primary deficit or surplus. Most countries have primary deficits, but Italy has a surplus which, according to IMF estimates, even beat Germany last year.

Only just over 55% of Italy's working age population have jobs

Growth priority?

The last two and a half years have been kind to Italy in one important respect. Government borrowing costs have come down dramatically from the unsustainable levels they hit in late 2011.

The effective interest rate on 10-year Italian government debt went to well over 7% then. Now it is about half that, a level that is manageable.

The improvement was partly due to the departure from government of Silvio Berlusconi and then the European Central Bank president Mario Draghi committing to do "whatever it takes" to preserve the euro.

The reform agenda for Mr Renzi's government is about addressing these problems. Faster growth appears to be his priority and there are signs that he might be willing to let government borrowing rise in the short term.

It is worth spelling out that Italy remains by any measure a rich country and many people envy many things about the quality of life there.

But compared with its neighbours and the rest of the world it has slipped. Italy could be a lot richer.

- Published17 February 2014

- Published1 June 2015

- Published4 October 2023

- Published27 November 2013