Italy's Matteo Renzi - PM in a hurry to reform

- Published

One of Mr Renzi's most difficult changes is to tackle the rising number of migrants reaching Italy's shores

Matteo Renzi came to power in February 2014 with a promise of widespread reform, at the head of Italy's powerful centre-left Democratic Party (PD).

Before he moved into Rome's Chigi Palace, aged 39, his main experience in politics was as mayor of Florence. He had never been a member of parliament.

And yet it was barely two months after he took over the leadership of his party in December 2013 that he triggered the downfall of his Prime Minister and party rival Enrico Letta and swept into office.

His arrival in national politics was heralded as a sign of much-needed generational change in a country led for years by elderly men.

Even before he became prime minister he was known as Il Rottamatore ("The Scrapper") - a reference to his call to scrap Italy's political establishment, widely regarded as discredited, tainted by corruption, and as having failed the nation decade after decade.

Although he led the party to success in European elections a few months after becoming prime minister, his party's share of the vote in local elections in May 2015 dropped below 24% and he has still not contested a general election.

Charismatic mayor

Mr Renzi cut his political teeth as mayor of Florence, winning widespread praise for his promotion of the city and his handling of a substantial pedestrianisation plan.

But he was not without his critics.

Mr Renzi is in his own words "hugely ambitious"

One former Florentine councillor complained he was more interested in his Facebook updates than keeping tabs on the city's budget.

And opposition councillor Ornella De Zordo complained he was better at making promises than keeping them.

"He's used the slogan 'Said, Done!' many times," she said. "I would say 'Said, But Not Done!' because Matteo Renzi is very good at a communicational level - at making announcements.

"But when you look at his record, things are very different. He sells himself very well."

Man for change

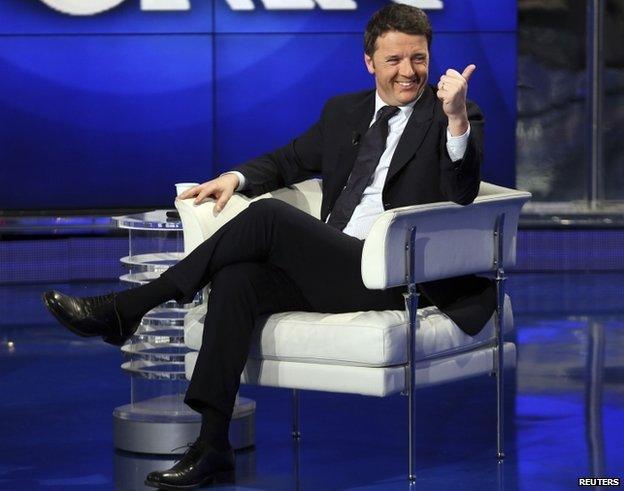

Mr Renzi is a confident, charismatic performer on TV

Matteo Renzi came to power believing politics could be done differently, and once called for scrapping the "old guard".

"People are weary and disillusioned," he said. "They don't believe anymore. I believe, and that's why I do politics - because I still believe."

Some saw echoes of the early years of former British leader Tony Blair, and his capture of the left-wing Labour Party in the mid-1990s.

Like Mr Blair, the reforming Mr Renzi sought to draw the PD into the centre ground, and reach out to voters usually more at home on the right.

Matteo Renzi: "In the face of human trafficking it's not a question of security or anti-terrorism"

In his own words "hugely ambitious", he promised "all the courage, commitment, energy and enthusiasm of which I am capable".

Exuding boundless energy, he comes across as relaxed on television and in parliament, and fast and fluent in his delivery.

While his success in power will likely be defined by the results of his push for reform, his time in office has been overshadowed by Italy's Mediterranean migrant crisis.

An estimated 45,000 migrants have arrived in Italy since January and more than 1,830 people trying to cross the Mediterranean have died.

Mr Renzi has accused other European countries of turning a blind eye to the drama unfolding close to Italy's shores, and the issue has played into the hands of his right-wing anti-immigrant opponents, the Northern League.

His cause has been helped by Federica Mogherini, a party ally who was appointed EU foreign affairs chief after the 2014 European elections.

Palace coup

In his quest for reform, he drew anger from the left of his party by holding a high-profile meeting at PD headquarters with Silvio Berlusconi, the former centre-right prime minister thrown out of parliament but still in charge of the opposition Forza Italia (FI) movement.

But Mr Renzi was defiant.

"It's a contradiction in terms to say 'You should have spoken to FI but not to Berlusconi'. Should I have spoken to [Berlusconi's fiancee's dog] Dudu?"

Mr Renzi arrived for his crunch meeting with then prime minister Letta in his small Smart car

Five days later he went to see the president in an Alfa Romeo Giulietta and was asked to form a government

Within weeks, Mr Renzi had moved towards a party coup. After a dinner with President Giorgio Napolitano, the young pretender was quoted as saying the government's batteries were running low and a decision had to be made on whether they needed recharging - or changing.

After visiting Mr Letta, he thanked the prime minister but said the country was at a crossroads: there was an urgent need for a new phase with a new executive. Not long afterwards, Mr Letta said he would step down.

Reforming leader

But running the beautiful Renaissance city of Florence and removing traffic from its central squares and streets is a far cry from leading Italy and reforming its politics.

He has succeeded in overhauling the electoral system, introducing a form of proportional representation that guarantees a big majority to the winning party, after a lengthy fight that alienated some of his own party's MPs.

But he faces more battles to come, as he tries to push through changes aimed at raising standards in Italy's schools.

He has already begun work on overhauling the labour market to boost job creation, but he aims to do more and faces opposition from trade unions and from within his own party.

- Published1 June 2015

- Published4 October 2023

- Published12 December 2014

- Published13 February 2014