How Amazon applied the Wall Street mindset to hi-tech

- Published

Online retail giant Amazon has developed rapidly under Jeff Bezos and one day may deliver orders by drone

Amazon is so much part of its customers' lives that it may be about to receive the ultimate accolade - becoming a verb. "If I want to know something, I'll google it. If I want to buy something, I'll amazon it," one of the company's fans told the BBC.

On average, every person in Britain spends just over £70 a year on Amazon. That's an impressive result for a business started on a couple of computers exactly 20 years ago.

Back in 1994, Amazon's founder Jeff Bezos threw in his promising Wall Street career to jump on the internet bandwagon, relocating from New York to Seattle to start his own dotcom.

That he was also a computer science graduate makes Amazon the product of an unusual merging of two cultures: the hard-driving world of East Coast finance and the techie, laid-back ethos of Silicon Valley.

'Uncomfortable' mix

Having Wall Street thinking at the very top of the company has given Amazon its edge in the ultra-competitive retail business. But that advantage is built on technology, where efficiencies in constructing its unique supply chain depend on incremental improvements in the algorithms that run the whole complex process.

Amazon shipped items to 185 countries over the Christmas period

The West Coast geeks have not always appreciated Mr Bezos' East Coast mindset though. Shel Kaphan, Amazon's first employee, fresh from Silicon Valley, was key to building the company's early tech infrastructure.

He fell out with Mr Bezos before leaving Amazon in 1999, and says the mix of Wall Street ways with what he calls the "hipster-saturated culture" of tech businesses was often "an uncomfortable combination".

Mr Kaphan says that at previous start-ups he'd worked at "there was a lot more of a sort of convivial attitude… team spirit, rather than an intense, hierarchical, driven attitude about things".

Another early staffer, Mike Daisey, found the punishing work schedule at Amazon hard to take: "The employees were willing to do absolutely anything to make things work." From management's perspective, "it's being able to inspire your employees not to have lives", he says.

He points out wryly that the dotcom tradition of allowing pets in the office isn't so much a sign of a relaxed attitude to work as a recognition that it wouldn't be safe to leave them. "Those dogs would have died because their master would never have come home."

Mr Daisey describes Amazon's annual company picnics as being the chance to be "let loose" with team games. Mr Bezos himself took part with gusto, which was "inspiring for people". It made them feel like they were "all part of one big dysfunctional family".

Harnessing brainpower

But the idea that the culture Mr Bezos has created is so demanding and abrasive that colleagues cannot stick it is not borne out by a look at his executive team, many of whom have worked with him for years

And for all his Wall Street drive, there's more to Mr Bezos' mentality than a desire to crush the competition through hard work and discounting prices. There is also an intellectual ambition to get to the bottom of knotty problems by the application of brainpower.

One of Mr Bezos' ideas is that when hiring new staff, "Amazonians" should always pick someone smarter than themselves. That way the overall level of intelligence at the company will keep on rising. (Apparently he has not found anyone smart enough to replace himself yet.)

The focus on brainpower is seen daily in the way meetings are conducted. They typically consist of the reading and discussion of a six-page "narrative", which is the distillation of an issue and a proposed solution put forward by one of the participants.

Jeff Bezos hates PowerPoint presentations, which he believes are an excuse for sloppy thinking

With narratives, arguments have to be made explicit in old-fashioned prose and figures, presented in detail so everyone can examine the case for themselves. So meetings often consist of people sitting and reading silently for 30 minutes, and making notes before cross-examining the author.

Former manager Dave Cotter says: "It's a really intellectual exercise that, once you go through it a few times, you realise how powerful it is." Now that he has left Amazon, Mr Cotter says he has discovered "most of the world does not follow that kind of intellectual rigour".

Mind-reading

Mr Bezos' commitment to following arguments to their logical conclusion has taken the company in some unexpected directions.

Its Kindle e-reader used its techie talent to develop a consumer product, which wasn't expected of Amazon, and its successful Amazon Web Services business rents out computing power to businesses large and small.

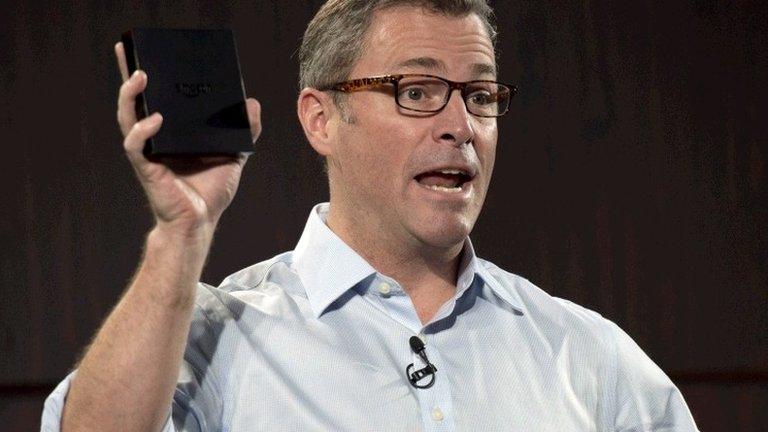

Amazon's Peter Larsen displays the Amazon Fire TV, a new device that allows users to stream video, music, photos and games through their television

And now Mr Bezos insists his long-term approach will one day turn the idea of delivering items by drone into a practical reality.

If the drones idea seems far-fetched, many former Amazon staff have learnt not to underestimate Mr Bezos' ability to make technology do what the company wants.

Talking to the BBC about Amazon in January, former editor James Marcus flippantly predicted: "I feel like we're six months away from them delivering [an item] before you order it, via some strange mind-reading machinery."

He was wrong: it wasn't six months but exactly three days later that it was reported that Amazon had been awarded a patent for a system of "anticipatory shipping", external that would start sending products to its customers before they had even placed an order.

Watch Amazon's Retail Revolution, part of the Business Boomers series, on BBC Two on Monday, 21 April, at 21:00 BST or catch it later on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published6 August 2013

- Published2 April 2014

- Published31 January 2014

- Published2 December 2013

- Published2 December 2013